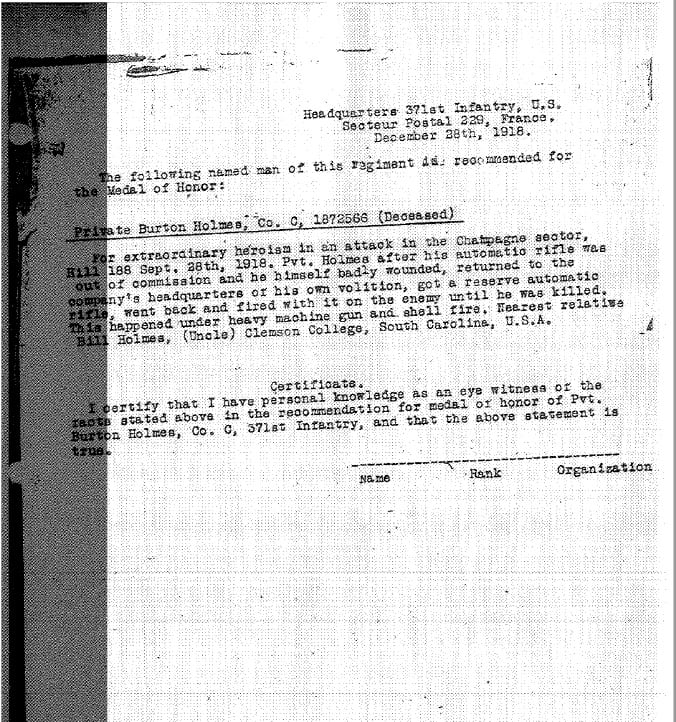

Out of a hailstorm of machine gun fire and heavy shelling, Pvt. Burton Holmes returned, badly wounded, to the 371st Infantry Regiment’s command post. His unit had been set up, lured out onto Hill 188 by the false promise of surrender, leaving them vulnerable to the surprise attack from the Germans.

But Holmes returned only because his automatic rifle was out of commission. He refused to be taken to the hospital for treatment. Instead, he got a reserve automatic rifle and rejoined the fight, firing upon the enemy until he died.

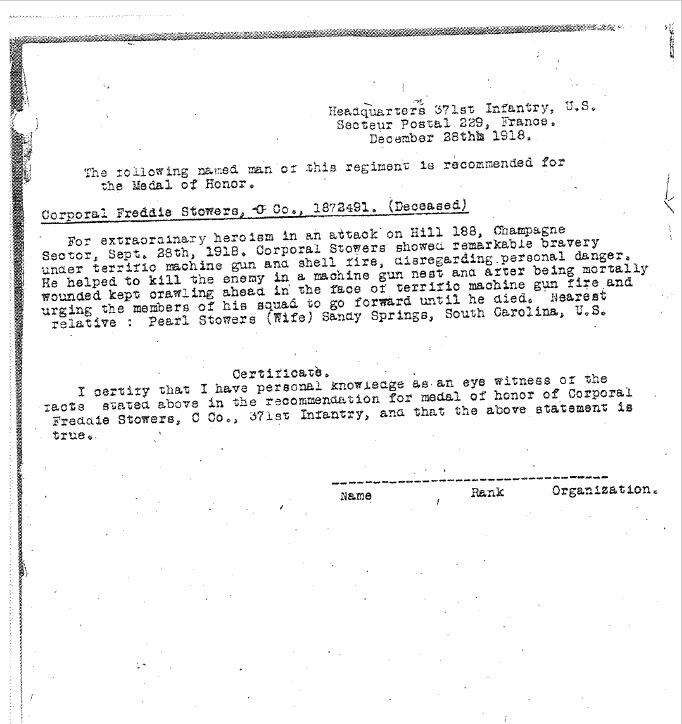

His try-or-die attitude was shared by all of Company C. His fellow soldier, Cpl. Freddie Stowers, continued to crawl ahead after being mortally wounded. He, too, died under fire, while encouraging the unit to continue advancing.

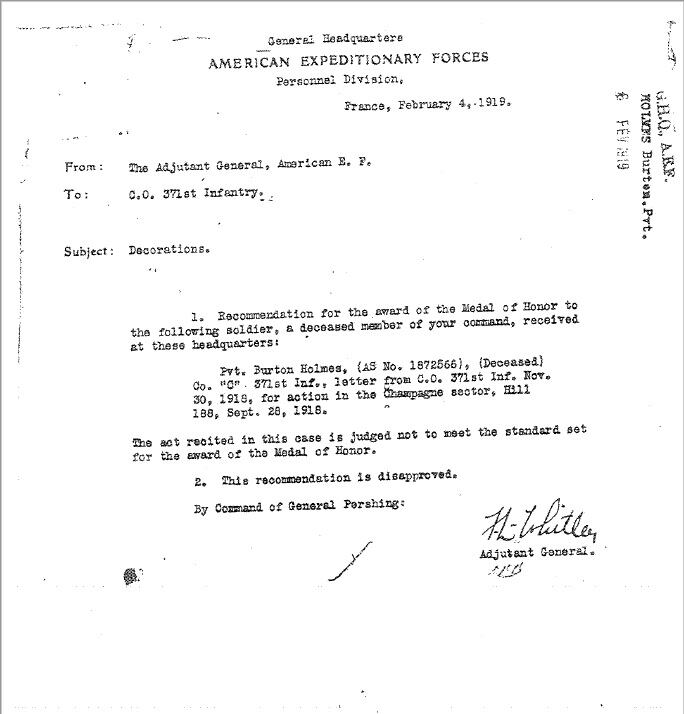

For their actions in the Battle of Hill 188, on Sept. 28, 1918, both Holmes and Stowers were recommended for the Medal of Honor.

It’s a special case, according to Dr. Jeff Gusky, ER doctor and National Geographic photographer. It is, as far as he can tell, the only case in U.S. history in which two African Americans died in the same battle and were both considered for the Medal of Honor.

But neither recommendation was approved; Holmes’ award was downgraded to a Distinguished Service Cross and Stowers’ recommendation was lost for decades.

Why? Gusky said it’s institutionalized and systematic racism. He is working with the American Legion and the American Battle Monuments Commission to get Holmes’ case reviewed.

“There was a concerted effort of preserving Jim Crow laws and the myth that African Americans were second class citizens,” said Gusky. “Imagine … how powerful this would have been in the American press … if word got out that there were two black soldiers who died in this ambush and were both nominated for the Medal of Honor.”

Stowers’ recommendation was uncovered in the late 1980s and awarded posthumously to his family in 1991, making him the first black Medal of Honor recipient for World War I. If Stowers’ actions deserved the Medal of Honor, Gusky said, Holmes’ actions do, too.

“Stowers was able to get the Medal of Honor, and if it was good enough [73] years after, you have to wonder, what was different?” said Verna Jones, executive director of the American Legion. “What was the distinguishing factor?”

Was it racism, which arguably increased during WWI in response to the standards of equality set by the “color blind” French Command that the 371st served with? Perhaps, Gusky argues, Holmes was not awarded the Medal of Honor because it would challenge the status of Jim Crow laws.

“That was actually Pershing’s policy,” said Gerald Torrence, director of Strategic Planning at AMBC, referring to Pershing’s secret memo: secret information sent to the French Command outlining how to “handle” black U.S. soldiers.

“You don’t treat blacks with too much respect, you don’t give them compliments in front of white officers, you don’t treat them too well, because you don’t want them to come home and be disappointed,” Torrence said, referring to the policy.

However, the team at AMBC says it’s a difficult argument to make, and still wants to conduct more research before bringing the case before the Army.

“The Army does not like to second guess,” said Col. Rob Dalessandro, deputy secretary of AMBC. “And there’s nobody alive to say, ‘I saw what happened on that hill and he deserved the Medal of Honor.’”

The recommendation could have been poorly written, and there was no one advocating for Holmes, a poor, illiterate cotton picker from rural South Carolina, drafted into the 371st Infantry Regiment, a newly formed unit within the segregated 93rd Division.

An officer — a white officer, the only kind in the 371st — recommended him for the medal.

“It had to be a white officer who put him in, and it probably had to go through several levels before it could be downgraded,” said Michael Knapp, AMBC director of Historical Services. “He was given the Distinguished Service Cross, which they don’t hand out freely then or today.”

Their next step would be approaching the Army, which would review the case and, if they agree that it should be upgraded, would take it to Congress. But it’s all conjecture, according to Knapp.

“There are a few things I can say for sure. The Army of 1918 will not give an African American a fair shake,” said Knapp. “But can we say all four of us at this table for sure that Burton Holmes was reduced because he was an African American? We can’t say that.”

Regardless of the reason, Jones says it’s a wrong that must be righted.

“You have to go back and honor people who have done extraordinary things … We ask men and women [to put their lives on the line] every day, the least we can do is reward those acts of heroism,” said Jones. “I mean, how many of us would have done what he did?” said Jones. “Those are the things that you can’t mind going back to right.”

Gusky and Jones have reached out to Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina to advocate for Holmes in Congress. According to Gusky and Jones, Scott expressed his interest in the story and agreed to research it more. He did not respond to Military Times for comment.

It may be difficult to achieve, but Gusky and advocates at the AMBC and American Legion believe the cause is important and the story is unifying.

“These guys were victimized, but they were not victims in their minds,” said Torrence. “That’s why they would step up for something bigger than themselves and put their lives on the line and their blood on the line. They were not victims in their minds.”