Editor's note: This story was originally published Dec. 29, 2014.

Sept. 7, 2011, began as just another day in Afghanistan for Army Sgt. 1st Class Aaron Causey, an explosives technician with 760th Explosive Ordnance Disposal Company.

Halfway through a scheduled yearlong deployment, his unit received a call about a suspicious device in a culvert. The box, masked in tape with a long wire snaking from it, appeared to be a hoax but had to be investigated nonetheless.

As team leader, Causey moved gingerly into the ditch to check things out. The device, as suspected, was a decoy.

But another nearby wasn't. As Causey stepped, the unseen IED exploded, propelling the 32-year-old into a snarl of concertina wire, blowing off both his legs and driving metal shards into his shoulders.

The detonation broke Causey's arm, destroyed portions of his hands and left him a double amputee, with nubs where his lean, muscular thighs once were.

But it's the injuries he rarely discusses that will affect him for life as much as the loss of his legs: The blast ripped away one testicle and tore off one-third of the other, wounds that now require Causey to take testosterone every day.

The treatment maintains Causey as the man he is, but also comes with a devitalizing side effect. Testosterone replacement causes male infertility, an unwelcome result for a young couple starting a family.

Related: Surgery, treatments can restore injured troops' sexual function

"Aaron and I were only married a year when he left, so we hadn't yet planned for children," wife Kat Causey says. "Nobody tells you at pre-deployment briefs that you should be thinking about freezing your sperm."

Aaron Causey is among an unprecedented number of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans — 1,291 — who received devastating injuries to their groins, genitalia, bowels, buttocks and urinary tracts and lived to endure the recovery, from ongoing struggles with the psychological impact of losing all or a portion of one's penis or testicles to sexual dysfunction, infertility and other medical concerns.

In other wars, these troops — average age, 25 — would not have made it out alive. But just as improvements in combat medicine and evacuation processes have saved thousands of post-9/11 service members from dying of potentially fatal head injuries, these personnel also have survived.

And just like their head-injured brethren, they also face lifelong treatment and recovery — not only dealing with their physical injuries, which for some, include destroyed genitalia, but also coping with psychological issues that can cause sexual dysfunction.

Rarely discussed

Sex and intimacy is a topic that is rarely discussed openly among injured troops.

A handful of spouses and girlfriends publicly blog about it, but for the most part, it's a topic raised only in the hallways of Building 62 — the apartment complex that has housed some of the most severely injured troops at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, just north of Washington, D.C. — or behind closed doors in physicians' offices.

But for two days in December in the nation's capital, the subject not only was raised, it was embraced — openly, excitedly, with gusto.

The Intimacy after Injury conference, sponsored by the Bob Woodruff Foundation, Johns Hopkins Military & Veterans Health Institute and Wake Forest School of Medicine on Dec.11 and 12, featured military physicians, psychologists, social workers, spouses and wounded warriors themselves discussing the aftermath of catastrophic brain injuries, the damage they sustained to their genital regions and urinary tracts and the challenges of having sex after surviving such wounds.

"No one really ever addresses the sexual symptoms," said Andrea Sawyer, whose husband, retired Army mortuary technician Sgt. Loyd Sawyer, was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury after working in the Dover Air Force Base, Delaware, morgue and in mortuary affairs at Joint Base Balad, Iraq.

"We were constantly told it was the medication causing the problems," she said. "But they were not listening to me. From Day One, before he was taking any medication, it was not the same."

When troops are injured in combat, doctors often are consumed with saving their lives — stopping the bleeding, preventing infection and saving damaged tissue. Injuries to the sexual organs or a head trauma that may result in loss of libido often are regarded as problems that can be fixed later at advanced medical facilities back home.

But doctors, social workers and policymakers at the conference said actions can be taken in theater to facilitate long-term healing, sexual function and fertility.

And they urged those with the power to change doctrine and policy to do it.

'How's my junk?'

"As a trauma doctor, the first thing I heard from injured troops in theater was: 'How's my junk?' And I'd tell them, let's not worry about that now, we need to fix you up," said Cmdr. Paul Gobourne, director of the Sea Services Warrior Clinic at Walter Reed in Bethesda, Maryland.

"Now, I see these troops and when they ask, 'How's my junk?'' they mean, 'What am I going to do about sex?' "

Sexual function issues after injury are not simply a matter of mechanics. For many, they stem from a complex web of physical injury, brain trauma that disrupts hormonal regulation, psychological reactions including fear and performance anxiety, and even a lack of sex drive between couples when the the daily routine of caring for an injured service member changes relationships from "passionate, sexy couple" to a mundane caregiver/patient scenario.

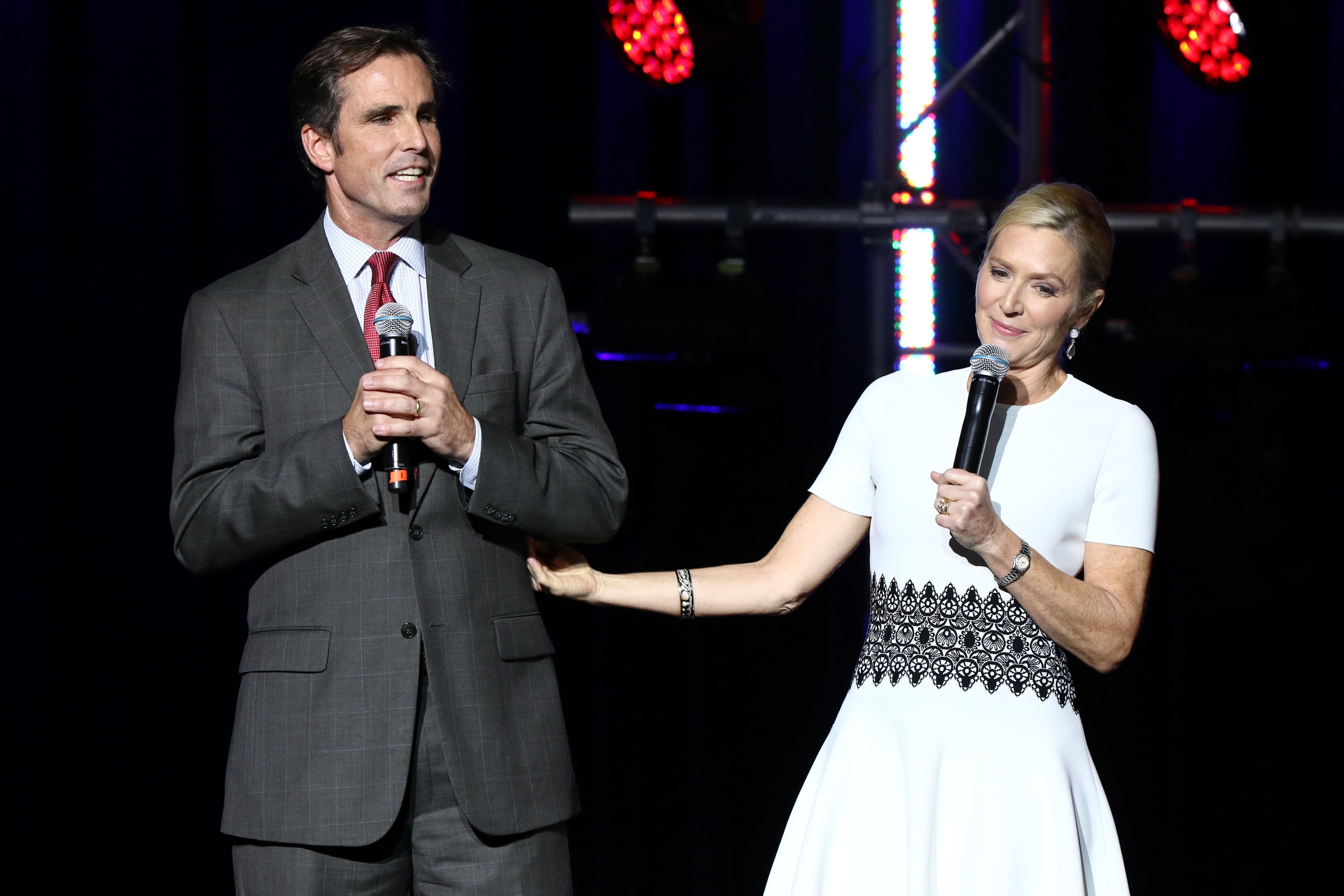

It's tough to feel sexy around someone who at times needs more care than a child, or, because of injuries, is so focused on healing that he is incapable of showing affection or love, said Lee Woodruff, whose husband Bob Woodruff suffered a severe head injury in an IED blast while covering the Iraq war as an ABC News correspondent.

Bob Woodruff and Lee Woodruff, at last year's Stand Up For Heroes event in New York City.

Photo Credit: Greg Allen/AP

"You don't know how alone you can feel when you are lying right next to them and they can't express their love. You keep wondering, 'how is this possible that we got here?'" Woodruff said.

One of the biggest barriers to addressing the issues is a lack of enthusiasm for discussing it, advocates say.

Woodruff said few, if any, of her husband's doctors wanted to talk about the couples' bedroom woes, and at military and Veterans Affairs hospitals, therapists are stifled as well, not even allowed to declare they are certified as sex counselors on paperwork or credentials.

"We can't even pull up a website that says 'sex' on it," said Catherine Vriend, chief of clinical health psychology service at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio. "That has to change."

A handful of military and VA treatment facilities have experts who can counsel couples on ways to improve their intimate relationships, but many of the programs are either not publicized or difficult to access, said spouses who have struggled for years to find appropriate counseling.

Sawyer said her husband is seen at a VA hospital where family counselor Emilie Godwin runs programs for couples, but she was unaware of the available services until she saw Godwin speak at the conference.

"It's great that these programs are offered at the larger centers, but what about the smaller facilities?" Andrea Sawyer said. "Many veterans don't live near one of the large VA hospitals ... and even if they did, they may not know what's offered. There has to be better communication."

Parenting concerns

On top of the impact these injuries have on sexual relationships, they also can affect troops' parental aspirations. Many of the nearly 1,300 personnel with genital wounds face problems of infertility, as do another 500 or so with other injuries, like Matt Keil, an Army infantry squad leader who became a quadriplegic in 2007 after he was shot by a sniper in Ramadi, Iraq.

Keil was medically retired after his injuries, and while he was eligible for fertility services at one of seven military hospitals that offer treatment while he served on active duty, he lives in Colorado, where the services are not offered, and he has a limited ability to travel.

Since fertility treatments are not provided by VA, the Keils paid out of pocket to receive in vitro fertilization that resulted in the birth of twins.

Matt's wife Tracy has testified before Congress on the need to change the VA policy on fertility services for injured veterans. She argues that military couples shouldn't have to pay out of pocket or turn to charities for help in starting a family.

IVF treatments can cost upward of $20,000 through a private specialist.

"Since my husband was combat injured, VA is responsible for his care. And even though Tricare covers some fertility procedures, VA is responsible for providing all care related to his injury, but is prohibited by policy from doing IVF or providing it. The issue was caused by my husband's service and it's not covered," Tracy Keil said.

"All too often, sterility is seen as an elective procedure or a luxury, but when you look at what's important in life, it often involves having a child, so we want to be able to provide everything we can," said Dr. Mark Payson, a reproductive endocrinologist with Dominion Fertility.

Tricare, the military health program that pays for private care, covers diagnoses of illnesses that can cause fertility and correction of any medical issues that might be the source of the problem but does not cover IVF or artificial insemination.

Those procedures are available at cost for patients that meet the criteria either on- or off-site at seven military treatment facilities, including the largest program at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland; Portsmouth Naval Hospital, Virginia; Fort Bragg, North Carolina; San Antonio Military Medical Center, Texas; Madigan Army Medical Center, Washington; National Naval Medical Center San Diego; and Tripler Army Medical Center, Hawaii.

And additional services such as as sperm extraction, preservation of embryos, IVF, artificial insemination and other fertility services are available at no charge to severely wounded personnel and their spouses as long as the member is on active duty.

The VA offers diagnostic services and treatment for some conditions but by law cannot offer IVF.

Legislative hurdles

Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., introduced legislation in 2012 that would have expanded fertility coverage for female veterans as well as severely wounded troops, to include options such as surrogacy and advanced reproductive health services for those unable to bear children without medical assistance.

The bill passed the Senate but stalled out in the House. Staffers from Murray's office attended the Dec. 11 conference to voice continued support for changes to VA policy.

"We want to make sure that when we in Congress make the decision to send people in harm's way, we are holding up our end of the bargain, ensuring that troops have access to care and the treatments that they really are entitled to," said Benjamin Merkel, a legislative aide to Murray.

Often left out of the discussion — but not in this conference — are young single service members who may spend more time thinking about preventing conception than looking ahead to preserving their fertility.

Stacy Fidler, the mother of 22-year-old Marine Lance Cpl. Mark Fidler, has become an advocate for such injured young men.

After Mark Fidler was struck by an IED in Afghanistan in 2011, he was mistaken for a British service member and evacuated from Camp Bastion under United Kingdom orders. His medical records indicated that he was scheduled for a sperm harvest just days after his injuries.

U.S. combat doctors do not harvest sperm from injured troops, although the first 48 hours provides an opportunity for saving what could be the service members' final gametes.

"As a mom, it was never my intention to get involved with this," Fidler said. "But at Building 62, I went to a family meeting with another mom of a single Marine with severe genital damage. I thought that as single men, they kind of get left out. When I asked my son's doctors about sperm harvesting, they said, 'We don't do that,' and my thought is, why don't we?"

It's not just single young men who might benefit from sperm harvesting and banking, Keil noted. "If they had taken sperm from Matt when he was injured, it would have made a significant difference in our quest to have twins," she said.

Opening the dialogue

Attendees at the conference pressed for improved counseling for patients, better communication on available services, increased access to medication and research for the severely injured and a public discussion in pre-deployment briefs about the risk of injury and family planning.

Most of all, they want to jump-start a public dialogue about this silent casualty of war.

"I hope this is the beginning of what will become a national conversation. ... Why can't we all start sharing and talking and just ripping the stigma off this? Penis and vagina ... I just said it," Woodruff emphatically stated.

One couple who has not been afraid to talk about their struggles with sex and fertility is the Causeys, whose story was profiled in a documentary, "The Next Part," which took home a special jury mention award at the Tribeca Film Festival earlier this year.

Doctors at Walter Reed were not confident Aaron Causey could conceive naturally, so they started him on medications to ready the couple for IVF treatment, even as he continued to have surgeries and recover from his other injuries.

But just as Dr. Robert Dean, andrology director at Walter Reed readied the couple for the long process of having a baby, Kat got pregnant the old-fashioned way.

Alexandra Jayne, or A.J., Causey was born last Jan. 27.

The Causeys may need to rely on assisted reproductive therapy if they decide to add to their family, but now that Causey is retired, they are not sure how they'd pay for it or when it would happen.

For now, they are enjoying their new family, building a house and taking things one day at a time.

Kat Causey hopes VA policy will change but she'd also like to see the discussion on the potential consequences of injury brought up during pre-deployment prep.

"What are they afraid of?" she said. "They need to talk about it ... If we'd sperm-banked before he deployed, we wouldn't have been faced with thinking about having a child during what was the worst time of our lives — his injury and recovery. This conversation has to start happening."

Patricia Kime is a senior writer covering military and veterans health care, medicine and personnel issues.