The Defense Department will monitor installations in 27 states, the District of Columbia, Guam and Puerto Rico for mosquitoes that can carry the Zika virus, according to a Pentagon memo released in March.

Hoping to ward off any spread of the potentially dangerous virus among troops and military family members, senior defense officials have instructed installation managers to increase surveillance for certain mosquito species and to eradicate them in housing areas, near child development and youth centers, around barracks and elsewhere.

According to the memo, 190 DoD installations are located in areas where mosquitoes capable of carrying Zika — aedes aegypti, aedes albopictus and aedes polynesiensis — may spread during the summer.

The memo calls for monitoring, trapping, testing and eliminating water sources that can act as breeding grounds for the pests.

"This must be a sustained effort in order to reduce and control the population … failure to implement a coordinated, sustained control effort will allow for a [mosquito population] that could transmit Zika," wrote Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs Dr. Jonathan Woodson and Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Basing Peter Potochney.

The Zika virus has appeared in 61 countries worldwide and has been linked to birth defects including microcephaly, a condition that causes infants to be born with underdeveloped brains and unusually small heads. Zika also can result in Guillain-Barre syndrome, a disorder that can cause paralysis.

Zika, dengue and chikungunya viruses and even yellow fever are transmitted by the ae. aegypti mosquito, the most common carrier, and may be carried by ae. albopictus, also known as the Asian Tiger mosquito, and ae. polynesiensis, a mosquito found in the South Pacific.

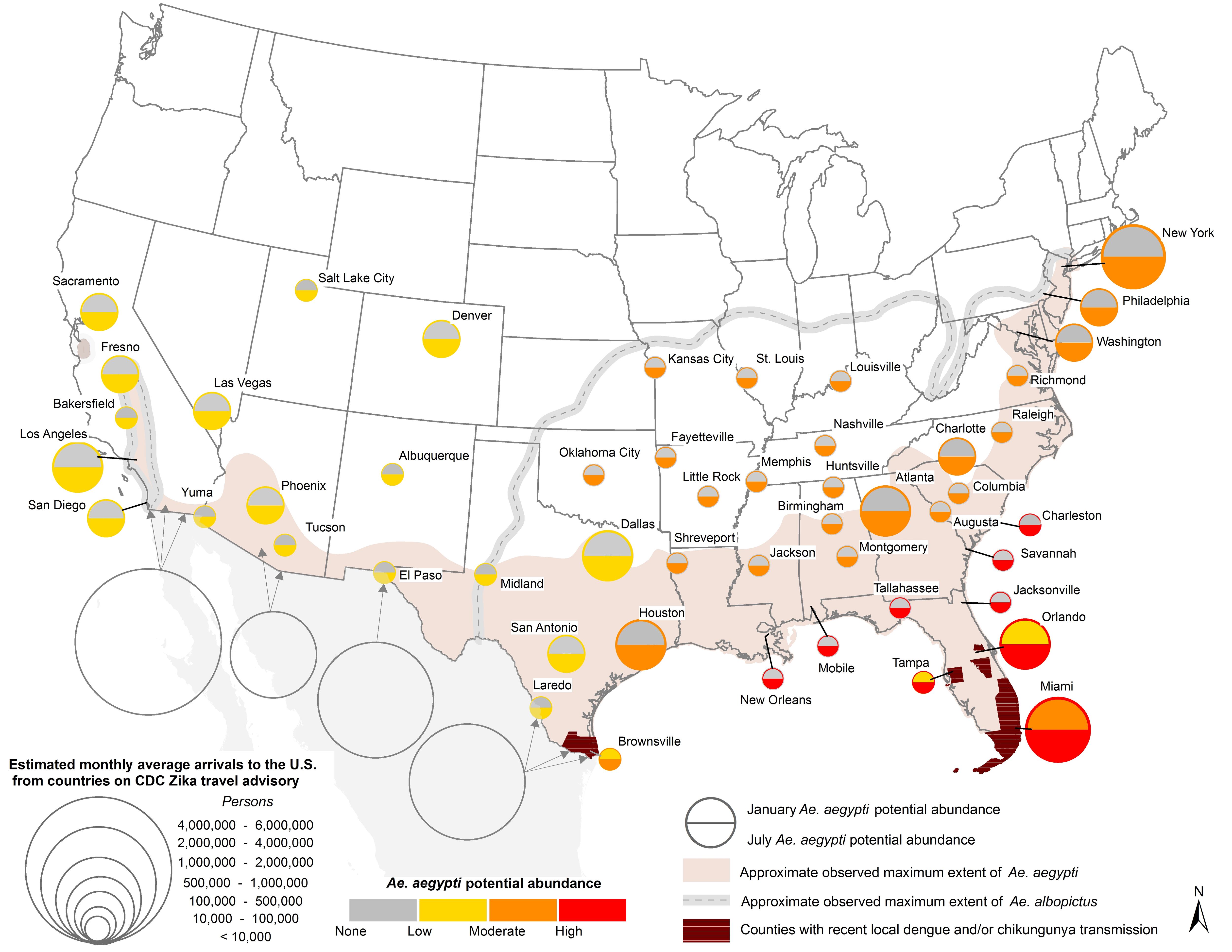

Most mosquitoes cannot survive in most of the United States year-round. But a study published March 16 in the journal PLOS Currents: Outbreaks found that nine of 50 U.S. cities analyzed could have a "high abundance of Zika virus-carrying mosquitoes by July."

And a few cities, mainly near Brownsville, Texas, and Miami, Florida, can harbor the mosquitoes year-round, according to the research, conducted by scientists from the National Center for Atmospheric Research, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, North Carolina State University, the University of Arizona, Durham University and Maricopa County, Arizona.

But does this mean a Zika outbreak is unavoidable in these cities?

Hardly, according to Chris Schmidt, one of the study's authors and an epidemiology and biostatistics research assistant at the University of Arizona.

"To try to put the data in perspective. This is a mathematical model we used to test different hypotheses — what could happen in various scenarios if all the variables were in place. It's not a forecast," Schmidt said.

The team examined weather patterns from 2006 to 2015 to simulate the seasonal abundance of ae. aegypti in the U.S. and found that largely, conditions are unsuitable for survival from December to March, except in the southern parts of Florida and Texas, where warm conditions can support a year-round mosquito population.

Florida in 2015 had 11 cases of locally acquired chikungunya, an indication that Zika also could spread there if introduced to the region by a traveler, Schmidt said.

"Cities in southern Florida and south Texas have both high seasonal suitability for aedes aegypti and the strong potential for travel-related introduction," Schmidt said.

Since the mosquito can live in all 50 cities examined in the study between the months of July and September, Schmidt stressed that mosquito control measures are advisable, even though the likelihood of a widespread outbreak is slim, since most people have access to air-conditioned residences and offices, and local governments in many states practice mosquito abatement.

"Our study is not predictive, necessarily. It is designed to lead a discussion and encourage communities not to panic about Zika but not be complacent either," Schmidt said.

Likelihood of the spread of mosquitoes capable of carrying the Zika virus this year based on climate data from the past decade.

Photo Credit: Andrew J. Monaghan et. al./PLOS Currents: Outbreaks

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention held a summit for state and local health officials April 1 on combating the Zika virus in their communities. CDC Director Dr. Thomas Frieden said the federal government does not expect widespread infection if local transmission occurs.

Still, communities must be vigilant in tamping down on mosquito populations to prevent transmission, said White House Deputy Homeland Security Adviser Amy Pope.

"If we wait until we see widespread transmission in the United States, if we wait until the public is panicking because they're seeing babies born with birth defects, we will have waited too late," Pope said.

Military bases certainly will be doing their share to prevent the spread of disease-carrying mosquitoes.

According to the instruction, they are to trap mosquitoes to determine whether they are ae. agypti and send them to be tested for Zika. They must reduce all potential water sources for breeding and have a response plan if a mosquito tests positive for Zika or another virus.

The U.S. has seen 312 cases of Zika in 35 states and D.C., all related to travel, with the exception of six sexually transmitted cases. Of the 312 cases, 27 were pregnant women.

There have been 325 locally acquired cases reported in Puerto Rico, 10 in the U.S. Virgin Islands and 14 in American Samoa, according to the CDC.

Patricia Kime covers military and veterans health care and medicine for Military Times. She can be reached at pkime@militarytimes.com.

Patricia Kime is a senior writer covering military and veterans health care, medicine and personnel issues.