In the weeks preceding his death, Janos Victor Lutz — "John," as his friends knew him — told VA doctors he was slightly depressed over a breakup with a girlfriend, his ailing service dog and his lack of focus after serving in the Marine Corps.

The Iraq and Afghanistan veteran told his psychiatrist and a therapist at the Broward County (Florida) VA Outpatient Clinic that he had been suicidal a few weeks prior and had asked his mother to secure his guns and dole out his medications.

But he also said he wasn't considering self-harm at the time of his appointments and had no plans to commit suicide. He complained that a medication he'd been given for anxiety and insomnia, temazepam, made him excessively sleepy and said he'd stopped taking another — buproprion for depression — months before but didn't say why.

According to VA records, the doctors encouraged Lutz to return to buproprion and switched his second medication to clonazepam, also known as Klonopin, a drug similar to temazepam used to treat panic attacks and sleep problems.

Because Lutz had tried three years before to commit suicide by overdosing, his psychiatrist ordered "a short supply of medication for safety precautions" on Jan. 4, 2013.

The next week, Lutz again saw his therapist and psychiatrist. He told physicians he'd been sleeping better on Klonopin, and according to VA records, asked for a dosage increase. He told his physician he was not feeling suicidal.

The following day, Lutz took a bike ride, went shopping with his father, and, according to his mother, appeared to be "at peace."

But later that day, the former Marine machine gunner returned to his childhood bedroom and ingested large amounts of morphine, buproprion and Klonopin along with a few beers.

He was found on his floor, the letters "DNR" — for "Do Not Resuscitate" — written on his forehead in black marker.

"Mom, there isn't anything I can say to apologize for this. I love you. … This is also not your fault. I did not use the meds I gave you. These are new prescriptions I picked up the other day. I would [have] done anything to kill myself. No one could have stopped me," Lutz wrote in a farewell note.

He was 24 years old.

Since that dark day in January 2013, Janine Lutz has done everything to help veterans with PTSD, including creating a foundation in her son's name for combat veterans, organizing motorcycle rides to raise PTSD awareness and funding law enforcement programs for first-responders who deal with veterans.

But her son's death continues to gnaw at her, given that just the month before, he had told her he feared for his life and asked her to lock away any means he had to kill himself.

Why, she wondered, did VA give him more drugs? Why did VA not heed its own clinical guidelines for treating PTSD, which recommend against using benzodiazepines like Klonopin and temazepam? And why — especially — would they prescribe a drug she thinks made her son feel suicidal?

"The drugs they are pushing on all veterans, not just my son, is not helping. I think we know that these drugs are killing them," Janine Lutz said in an interview with Military Times.

The FDA insert for Klonopin states that the medication "may cause suicidal thoughts or action in a very small number of people, about one in 500."

Lutz had been prescribed it before: at Camp Lejeune Naval Hospital in North Carolina, by civilian providers at an in-patient mental health facility and elsewhere.

But each time, the medication was stopped for reasons not mentioned in the records provided to Military Times.

And Lutz was prescribed other drugs that left him antsy and anxious, according to his records.

The multitude of medications he received throughout his treatment, along with what the family believes is VA's disregard for tracking those medicines and VA doctors' lack of understanding of how certain drugs affected Lutz, led the family to issue a demand letter claiming wrongful death as a result of medical negligence — a precursor to filing a lawsuit, according to attorney John Uustal.

They will seek monetary damages of a sizable enough amount "that forces VA to change" the way it treats all veterans with PTSD, , Uustal said.

"If you look at the records, [Lutz] was never treated right, from the beginning. They never worked up for brain injury, they never did a proper treatment for PTS, they never involved the family. … Real treatment takes time and money and VA just has too many people to handle. Too many veterans who need too much care and not enough resources for them to handle," Uustal said.

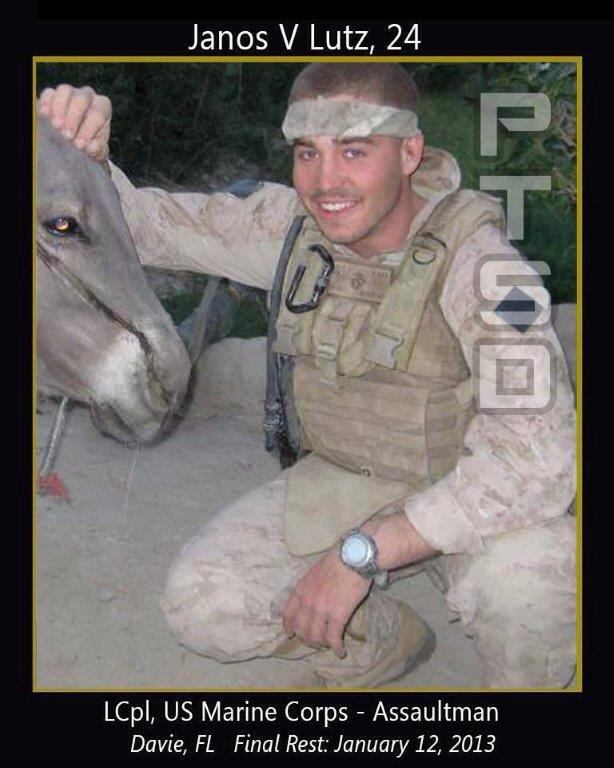

Former Marine Lance Cpl. Janos V. "John" Lutz.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Janos family

Lutz joined the Marine Corps in 2006 at age 18, becoming a machine gunner with 2nd Battalion, 8th Marine Regiment, at Camp Lejeune. The battalion deployed to both Iraq and Afghanistan, and in 2009 lost 14 members during intense combat in Helmand province.

On that same deployment, Lutz fell into an irrigation ditch wearing full combat gear, injuring his back and knee. He was also exposed to numerous concussive blast events.

According to medical records, he came home in pain, angry, depressed and wracked with survivor's guilt, and he sought treatment for substance abuse through the Marine Corps.

He tried to kill himself for the first time in 2010.

That effort put him in the hospital for three days and was the beginning of a lengthy struggle with mental health problems. Afterward, Lutz was in and out of military health facilities, in-patient private clinics and the VA, seeking to get his life on track.

Janine Lutz does not dispute that her son had ample access to medical treatment. But she believes his physicians did not thoroughly read his lengthy medical records, did not understand the extent of his injuries and didn't read closely enough to know that some of his medications caused him to contemplate suicide.

She also wants to know why, when a VA doctor wrote in Lutz's record that benzodiazepines should not be used in patients with PTSD — straight out of VA's 2010 clinical practice guidelines — that recommendation was ignored.

VA officials could not discuss the Lutz case specifically because the family declined to sign a privacy waiver.

But a VA spokeswoman said the department has clear guidance for treating patients with PTSD, and although those guidelines recommend against the use of benzodiazapines to prevent PTSD symptoms, the recommendations also note that patient cases are complex, and in some cases, such medications may be warranted.

"Clinical practice guidelines are intended for use as a tool to assist a clinician/health care professional and should not be used to replace clinical judgment," the spokesperson said.

In fiscal 2012, VA issued benzodiazapines to 28 percent of the 640,000 veterans seen for PTSD, down from 31 percent in 2009.

Overall prescriptions at VA for these drugs have declined as well, from 2.68 million in 2010 to 2.4 million in fiscal 2014.

Although benzodiazapines have their drawbacks, to include being addictive and possibly enhancing the fear response following trauma,they also have some valid uses –stopping panic attacks from escalating, easing sleep disorders and helping agitated patients at high risk of harm to themselves or others,said University of California-San Francisco psychiatrist Dr. William Wolfe, who is not involved in the Lutz case but treats veterans with PTSD at the San Francisco VA Medical Center.

The VA's clinical practice guidelines recommend against their use in patients with PTSD due to "lack of efficacy data and growing evidence for the potential risk of harm."

Though it is generally best not to initiate benzodiazepine use in patients with PTSD, Wolfe said, physicians often must prescribe them in patients who come to them already taking those medications, because abruptly stopping them can incur serious risks.

"It's a conundrum. Often times our choice may be between something that seems to be risky or another option that's risky -- inadequately treating," Wolfe said.

According to data furnished by the office of Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., the suicide rate among veterans ages 18 to 27 receiving care at VA medical facilities is 79 per 100,0000 person-years, substantially higher than the rates across the active-duty military of 18.7 per 100,000.

To address this profusion of deaths, VA has in the past two years increased the size of its mental health staff to provide better access to care, bolstered its crisis hotline capacity and added peer counselors and additional resources to reach veterans who need it, according to VA officials.

"The health and well-being of the men and women who have served in uniform is the highest priority for VA. VA is committed to ensuring the safety of our veterans, especially when they are in crisis," the spokesperson said.

But despite receiving consistent care and being asked whether he felt suicidal at every appointment and being monitored for medications, Lutz still died — because, his mother insists, VA doctors didn't follow their own protocols.

The day before he died, a VA doctor prescribed 90 pills of morphine for pain while the psychiatrist increased his Klonopin dosage.

The psychiatrist wasn't aware that the other doctor had prescribed the morphine and Janine Lutz, who had been asked by her son to hold any medication, didn't know her son had appointments at VA.

"Speaking to his psychiatrist after his death, I asked, 'Don't you guys talk? You're his psychiatrist and he's telling [you that I took his guns and medicines away] and this still happened,' " Janine Lutz said.

Congress is considering a bill aimed at reducing suicides among veterans by encouraging psychiatrists to work at VA, increasing the length of time Iraq and Afghanistan veterans have access to automatic care at VA and requires VA to establish pilot programs in each region that create peer support networks for veterans.

The Clay Hunt SAV bill is named for another Marine, Clay Hunt of Houston, who died in 2011 despite actively engaging in treatment, therapy and outreach. He passed away not knowing that Marines from his unit lived within 15 miles of his apartment.

Like the Live To Tell Buddy Up Combat Outposts that Janine Lutz is trying to establish in South Florida to give post-9/11 combat veterans a place to socialize and support one another, the VA peer support pilot aims to ensure that veterans have a support network to share stories, information, assistance.

Such assistance would have helped John Lutz understand his traumatic brain injury, his PTSD and his struggles better, Janine Lutz said.

VA is expected to respond to Lutz's letter within six months of receiving it. If the department does not respond, the Janine Lutz will file a lawsuit, hoping it will shake VA to examine its policies that favor medicating veterans over providing alternatives and support.

"VA's current protocol is not working. It's failing. But they continue to do it. It's killing these veterans," Lutz said.

Staff writer Jeff Schogol contributed to this report.

Patricia Kime is a senior writer covering military and veterans health care, medicine and personnel issues.