source GAIA package: Sx_MilitaryTimes_M6201310303130015_5675.zip Origin key: Sx_MilitaryTimes_M6201310303130015 imported at Fri Jan 8 18:18:09 2016

One of the most serious and prevalent injuries in the military is also one of the hardest to recognize and diagnose.

More than 250,000 troops have sustained traumatic brain injuries, most of which are classified as "mild" and don't even cause a loss of consciousness. But the lingering effects can last forever, subjecting troops to anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress.

"The short-term effects might not be terrible, but long-term effects certainly could be," said Maj. Edward Dice, who recently received a Purple Heart for a 2007 improvised explosive device blast in Iraq. "If they are not always right out there in front of you, you might overlook them."

Airmen who received the Purple Heart for TBI are sharing their stories to try to help others identify symptoms and seek treatment. And across the services, troops are receiving Purple Hearts for TBI under guidelines that took effect in 2011 — affording them greater access to the medical care they need. So far, about half of the airmen who have submitted packets for the medal have received the award.

'See how you feel'

Dice didn't normally man the guns on the Humvee, but it was a hot day and his gunner looked tired. Dice and his 10-plus vehicle convoy had been on the road for more than eight hours in the Iraqi heat on June 23, 2007. The Red Horse squadron started out in eastern Iraq, heading through Baghdad to go north to Tikrit. IED-clearing vehicles had already found three roadside bombs.

"We were dealing with a lot of enemy activity," Dice said. "The element of risk was high, but we got done what we needed to get done."

On the drive, the gunner started to show signs of heat exhaustion, so Dice switched spots to give him some shade and water.

Just 10 minutes later, they were hit by an IED.

The blast hit Dice hard. Doctors would later say he sustained a concussion from both the blast wave and hitting his head on the turret. He can't remember if he lost consciousness. And after the group returned to its contingency operating base, he was told to get some rest and see how he felt in the morning.

"The information and awareness of TBI and concussion and blast injuries wasn't very prevalent," he said. "It was just relax, and see how you feel the next day."

It wasn't until five years later that he realized he hadn't gotten the care he needed.

"I remember being kind of out of it," he said. "I was up all night, and in the middle of the night I decided to get a ride to the clinic. They ran tests. And when I returned to Nellis [Air Force Base, Nev.], nobody really asked me about it."

Unaddressed symptoms

After he returned from the deployment, Dice began suffering more symptoms, such as memory loss and anxiety. He saw specialists. He went to appointment after appointment.

"It was very disheartening," he said. "It wasn't apparent to me that they really knew what to do. They kind of left it at that at that time."

That was his third of five deployments. It took five years and another incident for him to understand the extent of his injuries.

In January 2012, while stationed in Colorado, Dice was in a car crash. He lost consciousness and suffered another concussion. This time, because he was stationed at Peterson Air Force Base, he was sent to Fort Carson, which had set up one of the military's leading treatment centers for traumatic brain injury. There, Dice started cognitive rehabilitation, teaching "his brain to work around the damaged parts," he said. He got a CT scan and an MRI.

"They were dumbfounded," he said. "They asked, 'How were you not treated for this five years ago?' I didn't have an answer for them."

In 2011, the Defense Department clarified its guidance in the awarding of the Purple Heart for traumatic brain injury. Troops had been eligible to receive the medal for TBI, but the additional guidance made it clear it can be awarded even if the service member did not lose consciousness, provided a medical officer certifies the injury would have required treatment if a medical officer had been available.

As of early February, more than 253,330 service members had been diagnosed with TBI since 2001. Of those, 77 percent were classified as mild, according to the Congressional Research Service. The updated guidance on Purple Hearts means those service members are eligible for the medal and the health benefits that come with it.

The Air Force has received 209 Purple Heart submissions for TBI since the guidance was issued, with 101 being approved, according to Air Forces Central Command.

Dice had originally put in for his Purple Heart in 2007.

"I was initially denied, and I was like 'OK, whatever,'" he said. "It didn't bother me that much, truthfully. The way I saw it was there are guys with plenty of worse injuries than me."

But as he progressed, it was clear that wasn't really the case. TBIs can linger and cause problems in the future. It's hard to diagnose and know if someone is really hurting.

"One of the key things that I've learned is … TBI is certainly one of those things that if treated immediately and properly, the lingering issues that a lot of guys go through later in life can be analyzed or completely eliminated," he said.

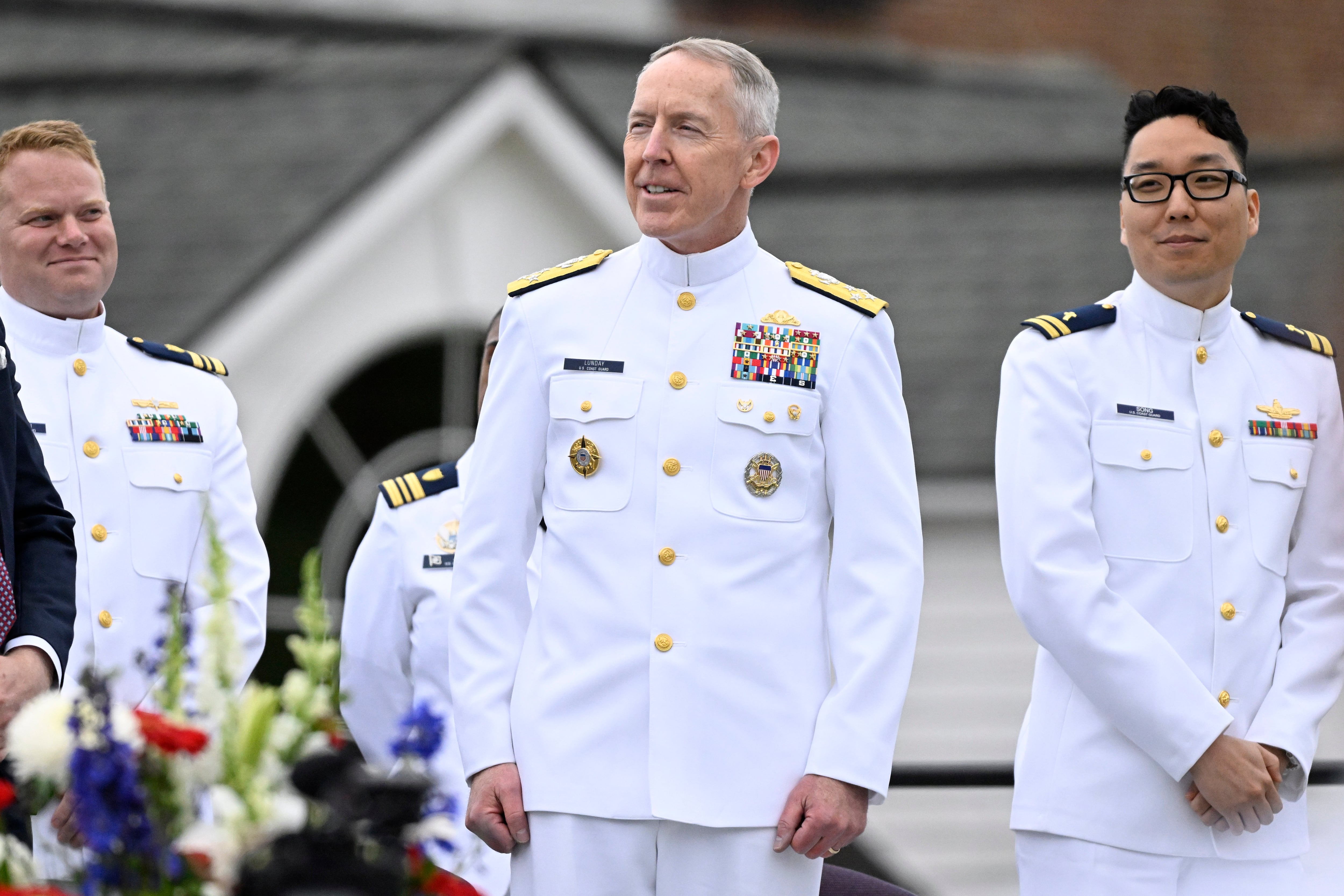

At Peterson, a colleague in the explosive ordnance disposal shop told Dice about the new guidance and put in his paperwork for him. Gen. William Shelton, commander of Air Force Space Command, presented him with his Purple Heart on Jan. 13.

"Being a Purple Heart recipient for TBI pays dividends when you get out," Dice said. It has helped him get care through the Department of Veterans Affairs at his new base, Joint Base Langley-Eustis, Va., where he is a reservist.

"I'm more focused on the future, to properly rehab my head," he said. "I wanted to be how I was before."

Evolving treatment

The initial treatment service members in the field receive has changed, as highlighted by other airmen who sustain TBI. On Jan. 16, 2012, Tech. Sgt. Michael Pasley, 56th Civil Engineering Squadron EOD team leader, was on his way to conduct a post-blast analysis of an Army vehicle out of Forward Operating Base Andar. As the team approached the scene, Pasley's vehicle hit a pressure-plate IED, which detonated under Pasley.

He remained conscious but began to experience dizziness, headaches and body aches. Back at the FOB, he underwent screening and was placed on mandatory 24 hours' rest and then another 24 hours' rest due to continued symptoms, Pasley said. EOD supervisors then urged the team to see medical support staff, where Pasley was diagnosed with a concussion and treated by an Army neurologist and an Air Force doctor.

Following the incident, he returned home for continued care, and Pasley's deployment leadership put him in for a Purple Heart. Ten months after the blast in Afghanistan, on Nov. 26, he was presented with the award.

Even though the knowledge and treatment of TBI has improved in the past few years, a lot more ground needs to be covered, the airmen said.

"TBI is still a relatively newly discovered injury, in my opinion," Pasley said. "The military community is just now starting to understand the long-term severity of these injuries. Now that discoveries are being made and new findings being discovered, I'm sure we will learn vastly about this injury."

Care is improving, and facilities such as Fort Carson are able to treat troops better than ever before, but it all starts with a diagnosis and the airmen themselves. The first-line supervisors, wingmen, battle buddies and friends need to be aware of the symptoms and urge someone who could be suffering from TBI to receive care.

"It's the diagnosis that needs to be highlighted," Dice said. "If it's properly diagnosed, then you don't go down the hole of anxiety and depression and suicide. One thing can typically lead to another, and awareness needs to be brought to everybody.

"People need to speak up and get the word out."