source GAIA package: Sx_MilitaryTimes_M6201410302090006_5675.zip Origin key: Sx_MilitaryTimes_M6201410302090006 imported at Fri Jan 8 18:18:14 2016

The two framed photographs would stay until the end, when Maj. Gen. Margaret Woodward left for the last time the Pentagon office where she'd served an unlikely role at the end of an extraordinary 31-year career.

The two framed photographs would stay until the end, when Maj. Gen. Margaret Woodward left for the last time the Pentagon office where she'd served an unlikely role at the end of an extraordinary 31-year career.

Before she arrived here last June, Woodward had flown refueling planes in wartime and made history commanding an air campaign over Libya. Work in this office would prove more challenging than all of that. And it was a role she did not want, at least not in the beginning.

Gen. Larry Spencer, the Air Force's vice chief of staff, had insisted. With less than a year to go until retirement, Woodward found herself fighting an insurgency not on a battlefield but within the Air Force's own ranks, from a windowless fifth-floor office in the Pentagon.

Seven months later, during the last week of January, it was proving hard to go. Woodward, typically more tough than teary, was getting emotional.

The work was not finished.

But the two framed photographs, one of her husband in dress blues and one of an Irish sport horse called Wex, reminded her why it was time to go.

The job she didn't want started with a scandal. In the summer of 2012, dozens of basic training instructors at Joint Base San Antonio-Lackland were accused of sexually assaulting or having inappropriate relationships with Air Force recruits.

Gen. Edward Rice, then-commander of Air Education and Training Command, asked Woodward to investigate.

"General Rice will tell you this, too — I was angry," said Woodward, who was acting director of operational policy and strategy at the time. "It was really readily apparent to me they were picking me because I was a female. I never wanted gender to be a distinguisher. I was lucky enough to be in an Air Force where it rarely is. Whenever I'm exposed to it, I lash out."

Woodward had 60 days to deliver a report detailing how such widespread abuses had occurred. Two hundred interviews, 18,000 surveys and countless hours later, she did — with 46 recommended changes to basic training. The Air Force adopted all of them.

"It was an incredibly interesting process to go though. To this day, the team we put together to do that are some of my closest friends. And I think we did some really good work," Woodward said. "One of the things I've told airmen who have worked with me for 31 years: Often my biggest disappointments have turned into my greatest opportunities."

And so it went last June when Gen. Larry Spencer, the vice chief of staff, called Woodward into a meeting to ask if she would lead the Air Force's new sexual assault prevention and response efforts. The current office of four would grow to 32. Spencer wanted a general in charge. More specifically, he wanted Woodward.

The military had endured a spate of bad press, from Lackland to a three-star general's decision in February 2013 to overturn a high-profile sexual assault conviction to the arrest on a sexual battery charge three months later of the chief of the Air Force's sexual assault prevention and response office.

The ex-chief was ultimately cleared of the charge, but the damage was done. Soon after, a new Defense Department report showed sexual assault was on the rise in the military.

Woodward told Spencer she didn't have the answers.

"None of us do," she remembered him telling her. "We need you to go out and find it."

'Icon of the American Air Force'

Woodward joined the Air Force to fly. She was the daughter of a diplomat, the granddaughter of a World War I pilot who'd earned his wings in 1917 and worked as a barnstormer before giving up flying professionally, figuring there was no future in it.

Woodward told this story in her office four days before her Jan. 31 retirement ceremony. "I'm from a generation of people who don't think strategically," she quipped.

As a child growing up in Pakistan and India and, later, California, she never imagined women wouldn't be allowed to fly. A high school guidance counselor broke the news.

"It was such a shock to me. I was like, no, they're going to have to change it, because this is my destiny," Woodward said.

In 1978, two years after the Air Force opened pilot training to women, Woodward headed to Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Florida. She was still a freshman when she met Dan Woodward, a fellow student with an instructor rating. He also wanted to be an Air Force pilot.

On a flight to Orlando that year, Dan let Woodward take the controls of his Mooney. It was the first time she'd actually piloted a plane, and she shared the news with her mother.

"If he can teach you to fly," she told Woodward, "you'll be great together."

When they married in 1981, the groom wore his dress blues. It was, Dan would say in an interview at Embry-Riddle some three decades later, his best day in uniform.

Woodward joined Dan at Columbus Air Force Base, Miss., in 1983. Fighters would remain off-limits to women for another decade, which left Woodward with few options. But they were enough.

Woodward became a T-38 instructor pilot — a small coup since Dan, too, was on the T-38.

"I was really lucky. I had a commander who was a little forward-thinking who said, 'If she wants to fly the 38 I don't see why her and her husband can't fly together,' " Woodward said. "I absolutely loved flying in little airplanes, going upside down and pulling Gs."

When people asked if she wanted to be the first woman fighter pilot, she told them she didn't want to be the first at anything. She did not aspire to reach the rank of general someday, or to fly into Panama on the first night of the 1989 invasion, or in the Kosovo conflict a decade later, or to command air refueling missions in Iraq and Afghanistan, all of which she did.

Nor did she imagine she'd be the first woman to direct an air campaign, over Libya in 2011, which earned her a spot among Time magazine's 100 most influential people that year.

"I'm not a very long-visioned person that way. I think I was mostly enjoying being in the moment. I can never, ever remember having a goal beyond wanting to be really good at what I was doing in the current job. I loved all my jobs, especially command opportunities. But I don't ever remember thinking I want to go do that," Woodward said.

"That's how she ended up being so successful," Lt. Col. Jill Whitesell, a spokeswoman in the sexual assault prevention and response office, said during Woodward's interview.

Woodward waved off the compliment, but Whitesell continued. "You're not careerist, you're not doing things for the wrong reasons, trying to get yourself promoted. You're just doing a good job in the job you're in. I'm sorry, ma'am. It's true."

"I think I'm successful because I had Dan ahead of me as a role model," Woodward said. "I'm serious. I would watch him and learn from him. Every time I thought I was breaking a trail I realized he'd been there first and he showed me the way."

"She always tries to deflect any attention away from her," her executive officer, Lt. Col. Eric Westby, said outside her office later.

Woodward hadn't liked being singled out by Time magazine, she confessed, because it took away from the rest of the team that had come together on short notice and without the resources they really needed to get the job done anyway.

"The only reason she gives interviews is so she can talk about what the people under her do. She does care about every single person under her charge. She pours her heart into whatever job she's doing," Westby said.

Woodward demanded a lot but never more than she gave herself, he continued. And you always knew she had your back. "I've never seen anything like it. I think she actually should be much more of an icon of the American Air Force."

A final challenge

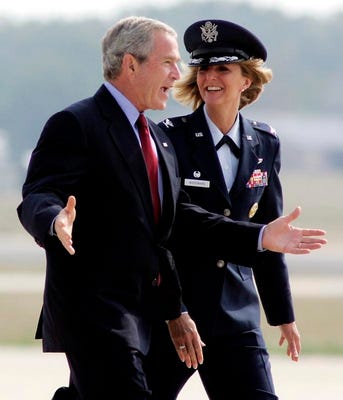

Thirty years in the Air Force left Woodward with too many memorable days to pick just one. But some stand out: Flying in formation with Dan. Seeing the U.S. aircraft in the sky around her as she entered Panama. Watching black smoke swelling against a brilliant blue sky over the Pentagon one September morning. Getting to know President George W. Bush as she escorted him between his helicopter and Air Force One at Joint Base Andrews, Md., despite his staff's admonishment to speak to the commander in chief only when the commander in chief speaks to you. Enduring four endless hours after the crash of an F-15 over Libya before learning the crew was safe. Proving that a mobility pilot could command an air campaign just as proficiently as a fighter pilot. Sponsoring, as the chief of safety, a group of airmen that planted an Air Force flag atop Mount Everest. And all the people who were a part of those moments.

"The quality of folks that come in, the dedication and selflessness, it's like something you never get to experience anywhere else," Woodward said. She paused, tearing up again. "When you have a group of people who are passionate about what they do, who are committed to something that's much bigger than themselves, and they come together as a team, there is absolutely nothing they can't accomplish."

Then came the final year, when she was counting down the days until retirement, when she would get to ride again — a love she'd given up decades earlier in order to fly. Woodward had her eye on Sir Wexford Seascape, an event horse who would retire along with her.

Now the Air Force vice chief of staff wanted Woodward to take on sexual assault in the last months of her career.

Before Lackland, she'd dealt with the issue only twice before. While commanding the 6th Air Mobility Wing at MacDill Air Force Base, Fla., in the mid-2000s, two airmen reported sexual assaults.

Woodward instinctively believed them. Others involved in the case questioned their stories, and both airmen eventually recanted. Woodward figured she'd been wrong, that the assaults really hadn't happened.

"The more you understand it [the crime], the more it really changes the way you view it. All the things we have our whole lives believed or taken at face value — what's a given, what's a known — it has turned that around," Woodward said in her office in December.

As head of sexual assault prevention and response efforts, she assembled a team of experts: a former first sergeant and a former squadron commander, lawyers and researchers, investigators and victim advocates.

"This is really what we consider an insurgency," Woodward said, and it would require an attack on multiple fronts. The Air Force would have to create a climate where victims felt comfortable coming forward and perpetrators found it hard to operate. And when they did, they'd have to be held accountable.

"Having learned everything I've learned, it's really common for survivors to recant for many different reasons. I look back on [the MacDill cases] and think odds are my initial impression was right, that both of them were very accurate in their reports," Woodward said. "They just reached a point where they had to withdraw. I think I would have reached out more to both of them and I hope I would have been able to keep them strong enough to be able to go through the process until the end. These cases are really hard to get convictions on. I still think it's very healing for our survivors to be able to report, to be believed, to go through the process no matter how difficult ... even if we aren't able to get a conviction."

The work moved Woodward so much she has decided to volunteer for organizations that support sexual assault victims.

"You can't be involved with this and not be moved," she said.

Some days left her frustrated because change doesn't happen overnight, Woodward said. And not everyone is open to it.

"But we've got amazing commanders out there who are really going out of their way to understand this issue," Woodward said. "I know it's in the right hands. I know progress is being made."

The next chapter

On Jan. 31, Woodward pinned on her grandfather's wings from World War I, a nod to the first pilot she ever knew to mark the end of her own career.

The retirement ceremony,at the Women in Military Service for America Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery outside Washington, D.C., began with a montage of photographs spanning more than three decades — Woodward in planes and with presidents and pinning on stars. There was Woodward on her wedding day, Woodward on vacation, Woodward in a pirate costume and a Darth Vader mask, Woodward laughing and standing stoically at attention.

"Each one of those pictures has a caption," said her husband, Dan, launching into dozens of stories from her career. "I had the great privilege of standing beside her ... through 32 years of marriage and 34-plus years of knowing her."

They never thought they'd both get the chance to retire from the Air Force. They thought one would have to get out in order for them to stay together. With each new assignment, they told themselves they'd stick it out for one more. In that way, the years and the decades passed. Woodward will tell you Dan made more career sacrifices than she did. Still, there were long stretches apart: They lived in the same house for only 10 months from 2000 to 2007.

"We got to this point in the usual way," Dan told their family and friends. "She came home one day and said she was ready to retire. I was surprised and asked her why. She said, 'It's time for me to spend more time with my big stud.' That's really how it happened."

From her seat nearby, Woodward laughed. Perhaps that's not exactly how the conversation went. But it wasn't far off.

"As soon as Dan retired, I longed to join him to make up for those lost years," Woodward said when it was her turn to speak at the ceremony.

The separations were hard but you endured them and you didn't complain because that was the choice you had made, she said.

Being apart was like going into an altitude chamber, where pilots learn to recognize symptoms of hypoxia, Woodward said. You take off your oxygen mask and try to do equations and look at the pictures in front of you, one of which is a pie chart of colors. Gradually, you notice the need for oxygen and throw the mask on.

"The pie chart explodes with a rainbow of beautiful colors," she said, and only then do you realize the chart had faded to shades of gray.