source GAIA package: Sx_MilitaryTimes_M6201410304070021_5675.zip Origin key: Sx_MilitaryTimes_M6201410304070021 imported at Fri Jan 8 18:18:15 2016

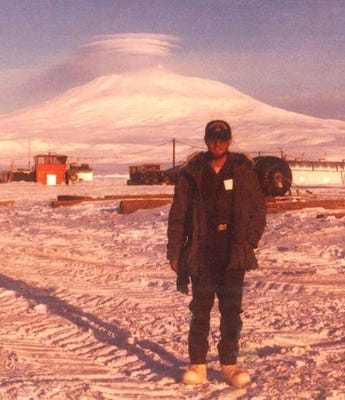

Nearly 35 years ago, a group of Navy helicopter aircrewmen helped the New Zealand government recover the bodies of more than 250 passengers and crew after their commercial airliner crashed into Mount Erebus, Antarctica's highest peak.

Nearly 35 years ago, a group of Navy helicopter aircrewmen helped the New Zealand government recover the bodies of more than 250 passengers and crew after their commercial airliner crashed into Mount Erebus, Antarctica's highest peak.

It was the deadliest disaster in the country's history.

The aviators finished their tour at Antarctica's McMurdo Station with Antarctic Development Squadron 6 and got on with their Navy careers and post-military lives. But in late 2012, retired Chief Aviation Electronics Technician (AW/NAC) Erich Eggers learned that the New Zealand Defence Force was looking for Americans who'd helped in the weeks-long recovery effort.

Eggers, now 55 and working for Iowa's transportation department, contacted the NZDF, who said they'd been looking for him, but a spelling error in his name led them to a dead end.

In 2006, the government had authorized a New Zealand Special Service Medal, the highest award given to citizens of other countries, for participants in Operation Overdue, the recovery effort's official name. Since then, a few dozen Americans have received the award, in addition to hundreds of New Zealand rescue personnel.

"I just kind of figured all of the other guys already had theirs," he told Navy Times in a March 11 phone interview.

Then the representative asked Eggers, who received his medal last summer, if he'd take a look at their list of crew members to help fill in any gaps. He asked if it included more than pilots, he said, and they assured him it did. He didn't see any helicopter aircrewmen, though.

"When this thing happened I was the youngest kid in the squadron," he said. "I was only 20, and they were all my instructors, they were all my big brothers. When I got the list and found out that I was only one on it, my heart kind of sank."

Through a Facebook page dedicated to his old unit, Eggers found four more of his fellow crew members , who will receive their medals April 2 in a ceremony at the New Zealand Embassy in Washington, D.C.

Responding to disaster

The squadron deployed to Antarctica in support of the National Science Foundation, transporting glaciologists, volcanologists and other researchers around the region as part of Operation Deep Freeze.

On Nov. 28, 1979, the squadron went on alert after New Zealand Air Flight 901 lost contact during a sightseeing trip.

The flight was a daylong tourist excursion aboard a DC-10-30 that left from New Zealand's Auckland International Airport at 8 a.m., spent the day flying over Antarctica, then returned to Auckland at 9 p.m.

McMurdo Station's U.S. military air traffic control was responsible for the flight, so when the pilot stopped responding to radio transmissions that afternoon, the Navy released a situation report. A ski-equipped LC-130 and two UH-1N Huey helicopters went to search for the plane and any signs of life the next day.

The LC-130 found the plane, which had slammed into the side of Mount Erebus. A lengthy and controversial investigation into the cause of the crash concluded the pilots and crew hadn't been informed of a change in the flight plan, which shifted flying coordinates to about 27 miles east of the previous path.

While the pilots thought they were flying over the McMurdo Sound, the investigation found, they were actually flying straight into the mountain.

A white cloud resting on the snow-covered volcano looked to them like the Ross Ice Shelf, a large piece of floating ice.

By the time the plane's warning system alerted the pilots that they were dangerously close to land, it was too late. Everyone aboard — 237 passengers from eight countries and 20 New Zealand crew members — died instantly.

Former Aviation Machinist's Mate 1st Class (NAC) Ken Becker, now 60 and working as a helicopter engineer for Boeing in Northern California, was on one of the Hueys, which flew to the crash site after the LC-130 spotted the wreckage.

"One of the first things we saw was the debris trail going up the mountain," he told Navy Times in a March 24 phone interview. "So it was sort of black and snow and ice and parts and pieces everywhere. We were able to recognize some of the larger pieces, you know, the tail with the New Zealand emblem on there."

Retired Chief Aviation Structural Mechanic (AW/NAC) Hector Rodriguez, now 60 and a robotics engineer in San Diego, was the crew chief of the first Huey to reach the site. That crew determined there were no survivors, but the wind and angle of the mountain made it too dangerous to land.

When conditions cleared up a few days later, the crews began the weeks-long process of bringing in New Zealand police and mountaineers to investigate, while flying remains back to Auckland for identification.

Providing closure

Eggers, Becker and Rodriguez all recalled Operation Overdue as the most significant mission of their Navy careers.

For Eggers, it was his first flight as a certified aircrewman, without an instructor. Becker and Rodriguez had flown rescue missions before but usually with better outcomes.

"In my mind, we were returning those bodies, those souls, back to their homelands so that they could be buried and for their families' sake," Becker said. "So from that perspective, it's a feeling of accomplishment that we were able to support that."

Becker and Rodriguez will reunite with retired Senior Chief Aviation Machinist's Mate (AW/NAC) Joe Madrid and retired Senior Chief Aviation Structural Mechanic (AW/NAC) Bob Cox for the ceremony in Washington, D.C.

"The only thing I can say is, I just don't want anyone to think that we're like, 'Oh boy, we're getting a medal,' " Rodriguez said. "For most of us, it puts kind of the icing on the cake of a big event in our lives, and there's nothing better than to get together for it."