BETHESDA, Md. — Running away from the sound of gunfire and IED blasts toward a shelter door, Army 2nd Lt. Rowan Sheldon suddenly stopped dead and gasped out an expletive: It wasn't an escape, it was a solid wall.

Behind him, all the medics and others in his platoon were carrying badly wounded soldiers, looking to him to lead them to a safe spot where they could triage, put on tourniquets, get patients on litters and move them away from the battlefield for treatment.

There are tough final exams. There are grueling final exams. And then there is the test at the nation's medical school for the military, in which students must navigate a simulated overseas deployment culminating in a staged mass-casualty incident with deafening explosions, screaming, smoke, gunfire and fake blood everywhere.

In the intense stress of that moment, sweating fourth-years have to pull up the lessons learned in class to bring order to chaos. Enough order, at least, to get people somewhere safe enough to start healing.

"It's the most important week of medical school," said Arthur Kellermann, dean of the F. Edward Hébert School of Medicine at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. It's the week when students camped at a National Guard base take on every challenge instructors can think to throw at them. Suicide bombers. Unraveling diplomatic relations. An influx of refugees. A sexual assault. And hundreds of wounded soldiers.

"We had a great plan going in," Sheldon said. "But they say no plan passes first contact with the enemy, right? We quickly realized there was no way this plan was going to work."

The country's only medical school for the military began in an unlikely spot: on the third floor of a corner lot in Bethesda, above a drugstore and a bank.

That was in 1972, not long after President Richard M. Nixon called for an end to the draft. Now the school sits on the grounds of Naval Support Activity Bethesda, next to the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, across from the National Institutes of Health.

The school serves 1,200 students, including 700 medical students among nursing candidates and those studying public health and other disciplines. Medical students pay no tuition in exchange for a commitment to serve across the armed forces; some are already active-duty members of the military while others have no military experience. They receive a commission when they enroll.

They learn the same medicine all doctors do, said John Prescott, the chief academic officer at the Association of American Medical Colleges. But the school is also "preparing them to work in hostile environments, to work and think with an international perspective, to think with a public-health understanding," he said.

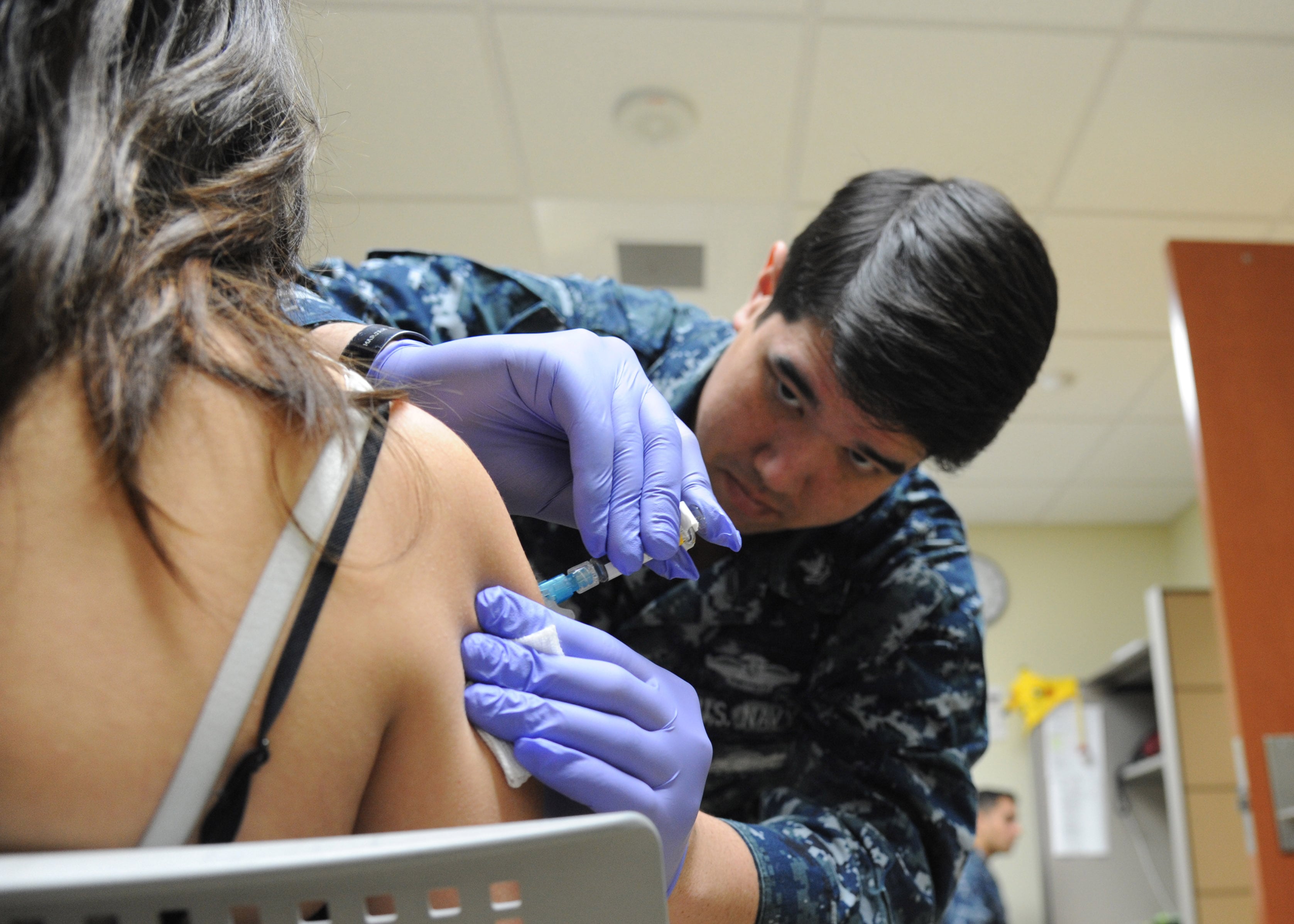

That means they learn to not only deliver a baby, but also to fire a gun and defend themselves in hand-to-hand combat. After they graduate in May, the fourth-year medical students will go on to residency programs.

First, though, they have to get through this test, the defining moment of their medical education.

A radio was crackling with orders inside a shipping container where men and women in combat fatigues were packing medical supplies, which were running short.

As part of their fourth-year clinical rotations, they had planned this simulated overseas deployment to "Pandakar," with a crash course on diplomatic relations, cultural issues and the advances of a rebel group fighting the U.S.-allied regime.

During a series of cold, rainy days on base at Fort Indiantown Gap in central Pennsylvania, they had dealt with challenges both simulated (a boiler explosion, a suicide bomber, an ambush, sniper attacks, a helicopter evacuation, a cholera outbreak) and real (physical and mental exhaustion, stress, uncertainty.)

A few miles away, the sound of rapid-fire gunshots, explosions and helicopters echoed through the woods, which were filling with thick smoke. Sheldon's platoon had prepared for facing a mass-casualty incident, but when it got to the scene, there were so many wounded soldiers and so much chaos that many of the students looked lost. Some tried to drag bleeding men to safety, or they looped arms around their necks to carry them.

Sheldon found the entrance to a shelter and improvised a triage area. There were patients screaming in agony, officers bellowing orders, a second wave of attacks that produced another flood of incoming patients, at least one man slumped lifeless on the ground and two "Pandakaris" wandering incongruously through it all.

Fourth-year student Shira Paul knew the chain of command, but once on the ground, she couldn't see or hear any leadership. She began helping people begging for aid nearby.

"He's got a gun!" a woman shouted suddenly, and someone else wrested away a pistol and restrained a man.

"I need help, now!" a medic shouted, bending over another patient. "He's bleeding from his head!"

There were 33 wounded and 24 there to help get them to safety. Meghan Quinn, a first-year student with fake blood coming out of her ears, kept staggering to her feet, dazed, and tottering around into the midst of the whole mess. Other patients clutched at the sleeves and pant legs of medics. Someone yelled for a tourniquet, and a man ran over unlooping his belt, then tightened it around a patient's upper thigh.

"Let's go! Let's go! Let's go!" an officer roared. "They need to be out of here in six minutes!"

They began loading people into a light tactical vehicle and a field ambulance, with a couple of soldiers ducking behind the wheels and firing at the insurgents nearby. "Let's GO!" the officer shouted, frantic and hoarse, as students heaved litters aboard and then scrambled up behind them as the trucks' heavy tires cut through the mud, rumbling away.

Afterward, back at the makeshift forward operating base, they sat on the grass to hear from instructors about how they had done. Everyone was exhausted, even students such as Anthony Romero, a large-framed 40-year-old with years of military service. Paul, a slight 25-year-old from south Florida who came to Uniformed Services University straight from Vanderbilt University, was so tired and sore that she warned the others: "I'm not sure I'm safe to lift a litter anymore."

Afterward, she realized clearly what she had done wrong. "I needed to find my leader, find out what I needed to be doing." The hardest thing all week, she said, was learning to be flexible.

Playing the role of surgeon in the mass casualty, Sheldon, 28, blew up their first plan for triaging patients inside the square shelter, and then a second one.

"Our triage was laid out with the sickest people who need care immediately. To do that, you have to keep walking by people who are still suffering. Every time you do that, you think, 'I can't do this,' and get on one knee, say, 'I'll be back to you as soon as I can. Put pressure on it,'" to stop the bleeding. "But if you do that every single time, you don't get the job done. You're trying to get people out, save as many lives as possible. You have to suppress that human side of you a little bit by understanding the overall goal of what you're doing."

It wasn't pretty. It wasn't perfect. But by the end, he was yelling: "You got this one? You got this one? I got this one, this one."

"And," he said, "we got everyone out."