![118540539[ID=26465019] ID=26465019](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/9087ec86f1c31763242d9a511c44275d43af3953/c=588-0-4871-3661/local/-/media/2015/04/27/GGM/MilitaryTimes/635657434791870464-TNS-powdered-alcohol-1.JPG)

But troops hoping to take a few pouches of powdered alcohol along on their next deployment or camping trip may have to wait awhile as states decide whether to regulate the dried booze known as Palcohol — and the company that makes it explores manufacturing and distribution options.

The product Palcohol — dried alcohol that can be mixed with a liquid to become an alcoholic beverage — received federal approval from the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau in March. The agency enforces laws regulating alcohol production, importation, and marketing and advertising.

But its official stamp does not mean the beverage mix, intended to be sold in liquor and ABC stores, will be available anytime soon.

According to Palcohol creator Mark Phillips, the product's parent company, Lipsmark, is deciding where to locate its manufacturing plant and watching as states debate the product's pros and cons.

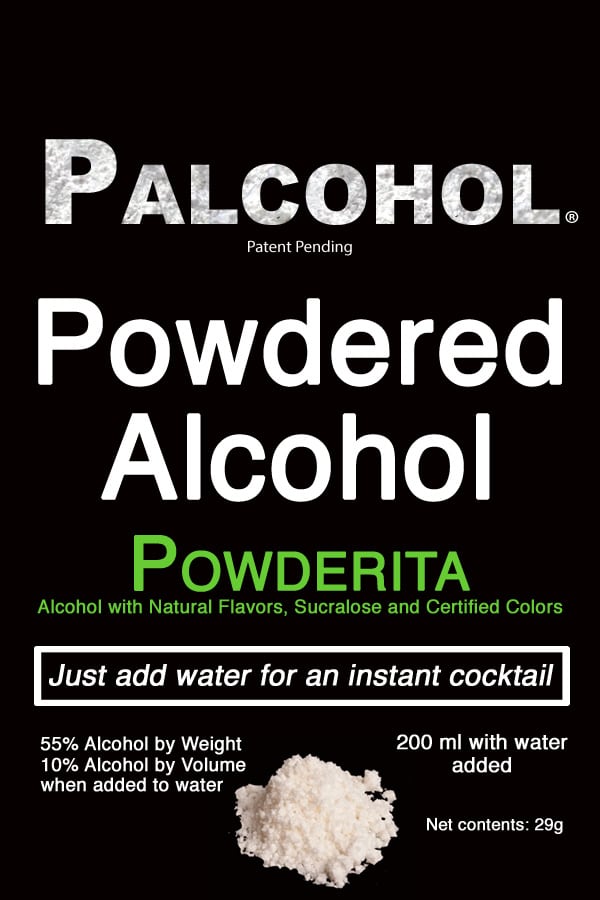

The label of the Powderita variety of Palcohol.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Palcohol

In many places, Palcohol, which will come in five different flavors — vodka, rum, cosmopolitan, lemon drop and "powderita" — faces an uphill battle. Due to concerns over public consumption, safety, and potential risk for underage drinkers, many states are moving to ban its sale.

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, Palcohol is already forbidden in six states — Alaska, Louisiana, South Carolina, Utah, Vermont and Virginia — and will be strictly regulated as concentrated alcohol in Colorado, Delaware and Michigan.

And more than 70 bills have been introduced in state legislatures to ban or restrict the product. If a state doesn't specifically ban or restrict its sale, then stores licensed to sell alcohol will be able to sell it.

But the biggest threat to Palcohol's commercial availability is Sen. Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., who introduced a bill on March 12, S. 728, to ban its manufacture, sale, distribution or possession.

Palcohol, Schumer says, "creates an immense danger to teens and others."

"I am in total disbelief that our federal government has approved such an obviously dangerous product, and so, Congress must take matters into its own hands and make powdered alcohol illegal," Schumer says in a release after the bureau's decision.

The concerns of Schumer — and others — center around the product's potential appeal to adolescents, who could slip it into their sodas or sprinkle it on food for a surreptitious buzz.

Parents have voiced concern that youth would snort it to achieve a direct-to-the-bloodstream high.

In a YouTube video, Phillips acknowledged that Palcohol could be snorted but noted that it would take an hour to snort the amount of powder that is the equivalent of a shot of vodka and says it would hurt. A lot.

"Why would anyone spend an hour in pain and misery snorting all this powder just to get one drink into their system?" he says.

Powdered alcohol is not new. General Foods in 1972 patented an "alcohol-containing powder," making a "high ethanol containing carboyhydrate powder which readily dissolves in cold water to form a clear, low-viscosity, colorless liquid."

Their efforts were successful, creating a product that made an "acceptable wine beverage" and could be sprinkled over fruit cocktail or added to Bloody Mary mix for a brunch treat.

But General Foods' product never materialized on store shelves. And while other companies and manufacturers have tried to bring it to market, no attempts had made it past the ATTTB until now.

Phillips says he decided to create a marketable product because he is an "active guy who likes to have a drink every now and then in places where bottles and mixers are inconvenient."

Palcohol creator Mark Phillips.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Palcohol

"When I hike, kayak, backpack, whatever, I like to have a drink when I reach my destination ... bottles are just impractical," Phillips says.

Palcohol, he says, is lightweight and would come in its own self-standing, just-add-liquid pouch similar to the foil packs of Capri-Sun and other sturdy, portable juice beverages.

"I see it as being good for any outdoor activity where weight is a factor and liquid is not convenient," Phillips says.

He also plans to market and sell Palcohol for other uses, such as fuel for camp stoves, a portable antiseptic, emergency fuel or as a dried concentrate for window washer fluid.

"There are many many more positive potential uses of Palcohol besides drinking it," Phillips says.

One packet of Palcohol contains about half a cup of the product and weighs an ounce. It equals one shot of liquid alcohol and is intended to be mixed with five ounces of liquid or water to create an alcoholic beverage of similar strength to a basic mixed drink.

It's more expensive than a rail liquor brand, however. According to Phillips, a packet would cost about four times the amount of an equivalent ounce of liquid alcohol.

Phillips says he is considering a number of locations for a Palcohol manufacturing plant, but concrete plans are on hold while state legislatures and the U.S. Congress consider whether to ban the product.

His commercial aspirations received a boost on April 14, when Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey vetoed a bill that would have banned powdered alcohol in the state.

Lipsmark is a Tempe, Arizona-based company.

"Once the bill was sent to the governor, I personally wrote him a letter to educate him about the product. People — critics — are making decisions knowing nothing about it," Phillips says.

In his veto letter, Ducey says it made sense to monitor the product but that a ban right now is inappropriate.

"I have instructed the director of the Department of Liquor Licenses and Control to review administrative rules to ensure that powdered alcohol is regulated to the same extent as other spiritous beverages," Ducey wrote.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., has called Palcohol a "tragedy waiting to happen" and supports legislation to ban it nationwide.

"It can be taken anywhere easily and therefore is readily susceptible to abuse," Blumenthal says during a press conference in Hartford on April 10.

Even if it's not banned nationally, it still may be a while before Palcohol arrives on store shelves. And officials with the military exchange systems say don't look for it in Class Six stores any time soon.

AAFES spokesman Judd Anstey says decisions on new products are made after monitoring customer demand and deciding whether a new product fits into AAFES' assortment of offerings.

"Currently, the Exchange does not have a contractual agreement with a vendor to carry powdered alcohol," Anstey says.

Officials for Navy and Marine Corps exchanges say their systems have no plans to carry the product.

Patricia Kime is a senior writer covering military and veterans health care, medicine and personnel issues.