It's been a humbling few weeks for the Pentagon's central strategy of training and equipping foreign forces to fight on the ground so U.S. troops don't have to.

In Syria, a yearlong effort to train and equip a moderate rebel force was abandoned as a failure.

In Iraq, the local army's campaign against the Islamic State remains stalled outside Ramadi despite support from daily U.S. airstrikes and thousands of boots-on-the-ground advisers.

In Afghanistan, the Taliban in September overran and seized a major city for the first time since 2001. A few weeks later, President Obama scrapped his timeline for ending the U.S. military mission there by the end of next year and said the Afghan army will need support from American troops into 2017.

The series of setbacks in short succession is prompting Washington to take an increasingly skeptical look at the train-and-equip model on which the U.S. military is hinging its strategy.

Congress is holding hearings about "security cooperation" policies. The Defense Department's inspector general is ratcheting up its scrutiny of the train-and-equip efforts. And military officials are facing new and pointed questions about when such missions no longer are worth the effort and should be deemed hopeless.

"I'm looking for some certain rules of the road, kind of like we have on the military intervention side with the Powell doctrine, you know, 'These eight preconditions must exist before you commit U.S. forces,' " Rep. Beto O'Rourke, D-Texas, said in an Oct. 21 House Armed Services Committee hearing on security cooperation issues.

Experts say clear-cut rules are hard to define for security cooperation missions. Obviously, U.S. train-and-equip efforts are more effective when the countries involved are not embroiled in a war, when they have stable central governments, strong economies, functioning ministries of defense and can physically secure their own borders.

Unfortunately, those conditions are rare in many of the places where U.S. military personnel are currently embroiled.

"The hard question is, OK, if you don't have all those things, do you engage anyway?" asked Rep. Mac Thornberry, R-Texas, chairman of the House Armed Services Committee.

"What if you're in a messy place without a strong political infrastructure to work with — do we not engage? ... Do we engage with much lower expectations of what can result?" I don't know the answers," Thornberry said.

Stonewalling in Iraq

The DoD inspector general recently shed new light on the details of U.S. train-and-equip efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan. The IG, an independent watchdog, has launched a series of reports spotlighting the effectiveness of security cooperation efforts, and on Oct. 22 announced a new investigation into the Pentagon's effort to train, advise and equip Kurdish security forces.

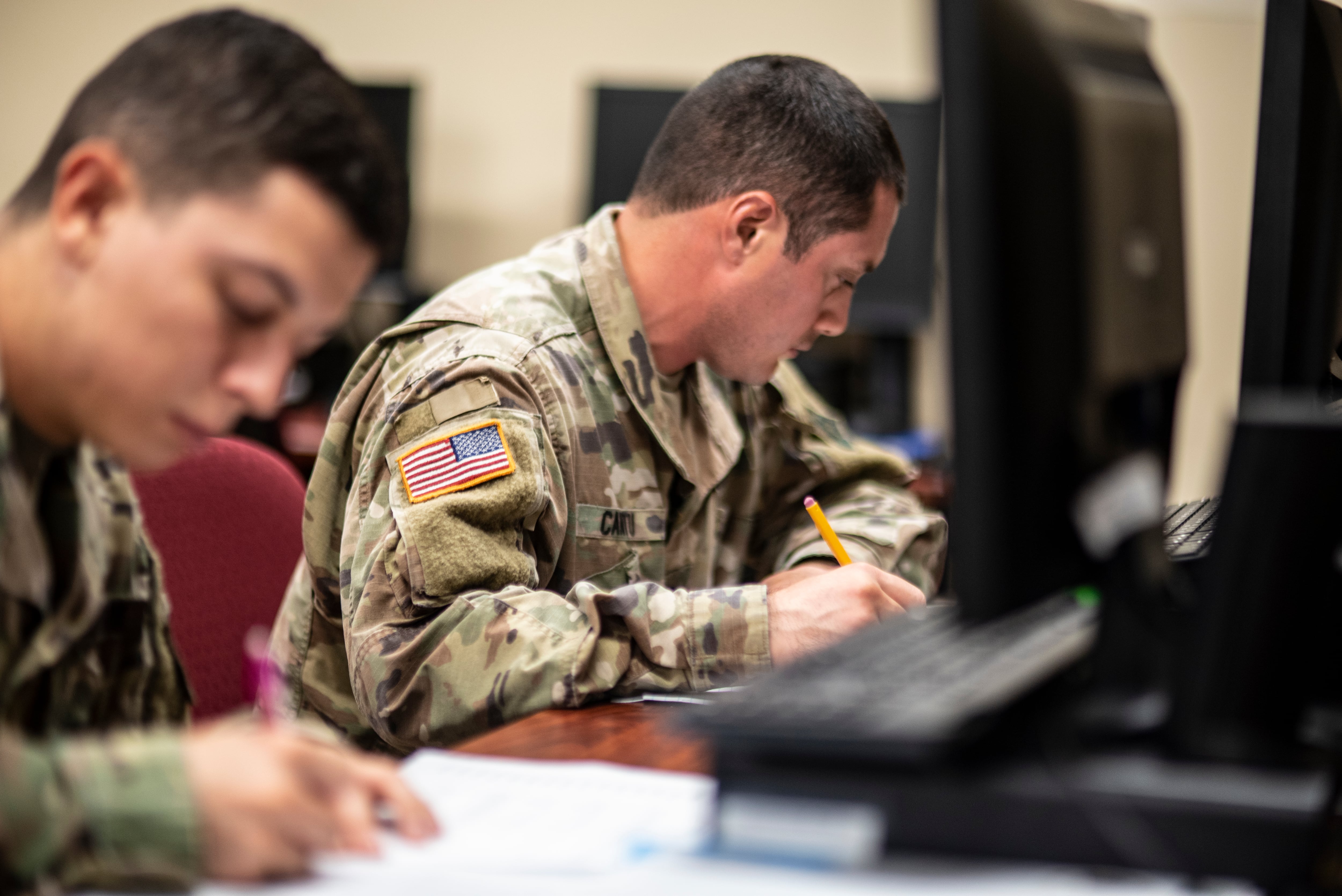

Staff Sgt. Taylor Rouse poses with Iraqi soldiers after their graduation from a six-week training course Feb. 13 at Camp Taji, Iraq. Rouse and other U.S. soldiers helped train more than 1,400 soldiers during the course.

Photo Credit: Staff Sgt. Daniel Stoutamire/Army

Another recent report focused on the current mission in Iraq, where nearly 3,500 American troops are trying to arm, train, advise and assist Iraqi security forces in their fight against Islamic State militants.

The report outlined what American troops found recently upon returning to a boots-on-the-ground training mission: only limited evidence of the previous U.S. training effort in Iraq that ended in 2011.

In the few years since, the Iraqi force had reverted to a manual, paper-based system for tracking supplies and equipment.

Iraqi troops were living in squalor: At Al Asad Air Base, there was no running water and the troops were using slit-trench latrines. There was no mess hall; soldiers were responsible for procuring their own food. And housing was overcrowded, with up to 14 Iraqi soldiers squeezed into individual "containerized housing units," where typically two or three U.S. troops would live.

Even basic trust and good will were in short supply, as Iraqi officers refused to grant their Americans advisers access to most weapons storage facilities, making it impossible for the U.S. personnel to assess what was on hand and what more might be needed.

That stonewalling and lack of cooperation posed a serious threat to the mission, the IG said.

The Iraqi army's "inability or refusal to conduct complete inventories of its equipment and supplies on hand, or to allow U.S. advisors access to supply warehouses," threatens to impede the U.S. training-and-equipping mission, as well as the Iraqi army's ability to sustain combat operations, the IG bluntly reported.

Lowered expectations

A team of national security experts told lawmakers on Capitol Hill that these train-and-equip missions are inherently fraught with challenges, and military and civilian leaders should avoid high expectations.

"One of the findings of our research is that you can't want it more than they do," Christopher Paul, a researcher with the Rand Corp., told the House committee in that Oct. 21 hearing.

"Willingness to fight, this is an incredibly difficult thing to assess," Paul said. "It's incredibly difficult to know how willing to fight a force is until they are battle tested. ... Lack of willingness can disrupt security cooperation at many different levels, any of which can result in delay, diminished success, or outright failure."

Even when the host-nation military is extraordinarily motivated, such missions still can fail if the government is ineffective or unpopular.

"Unless there is a legitimate, semi-stable political authority that can control a border and actually run a government, efforts to reinforce another country's military are going to have limited success," said Derek Reveron, a national security professor at the U.S. Naval War College.

Some shortcomings within the U.S. military itself also have contributed to some of the failures in recent years, experts said.

Several experts told lawmakers that a "rotational culture" hampers efforts to forge strong relationships with foreign militaries and follow through on new programs needed to support them.

Many U.S. troops also lack a solid "understanding of whatever culture and whatever military we're working with," said retired Air Force Gen. Douglas Fraser, who testified at the hearing.

"I just don't think we're very good at that," Fraser said. "We tend to mirror-image our perspective on other governments and other cultures, and we need to do a better job of understanding what's important within that culture."

Reveron agreed, saying the U.S. military's personnel system "is not producing sufficient talent to support these missions. American forces no longer operate in isolation and need an appreciation of the historical, cultural and political context of where they operate."

U.S. failures

The DoD IG also has found that many problems with these missions are rooted in the U.S. military's own culture.

In some situations in Afghanistan, U.S. advisers "lacked skill because Coalition leadership had not adequately identified the qualifications and experience necessary" for those personnel," according to an IG report released in March.

In addition, the IG noted, the U.S. military's promotion system continues to value traditional operational assignments with combat units over assignments advising and assisting foreign militaries. "There were few personnel incentives to attract more highly skilled and experienced candidates as advisors," the report stated.

Corruption often is cited as a key problem in the governments and defense ministries of nations in which the U.S. is engaged in train-and-assist missions. Yet the IG said U.S. officials may not be focusing on that issue to the degree warranted.

"Efficient and accountable resource management by these ministries was not an advisory priority emphasized in the early stages of U.S. and Coalition involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan," the report said.

Underlying many of the stalled train-and-equip programs is simple illiteracy. And U.S. forces often fail to fully appreciate how limited the education levels are in places like Afghanistan.

An Afghan air force C-130 Hercules pilot flies a training mission to Kandahar Airfield in Afghanistan last Nov. 23 with advisers from the U.S. Air Force's 538th Air Expeditionary Advisor Squadron to Kandahar Airfield.

Photo Credit: Staff Sgt. Perry Aston/Air Force

The result is foreign militaries filled out with units that might be able to run fire-and-maneuver drills but cannot maintain a larger command-and-control system or the technological infrastructure that an American-style command requires.

"Low literacy rates, inadequate generation and distribution of electricity, and lack of information networking capacity were command and control limitations inherent to Afghanistan," the IG's March report concluded.

'Free riders'

Many military experts worry that these multibillion-dollar security cooperation programs are creating "free riders" — allies who come to rely too heavily on the U.S.

While American officials often are eager to assure allies that the U.S. is not leaving anytime soon, that sparks concerns that "other countries will rely on the U.S. to subsidize their own defense budgets, creating a free rider problem," Reveron said at the Oct. 21 hearing.

Rep. Jim Cooper, D-Tenn., noted that in some respects, "security cooperation is almost a host-country stimulus program."

"We don't want the partner country to think that U.S. assistance is going to be there no matter what, because then they will fail to develop the capacity and capabilities that are necessary for them to be able to take on their challenges without U.S. aid in the future," O'Rourke added.

"When do we draw the line and say ... yes, I know we want to get this government up and running, but maybe they're not ready yet to do it with our dollars?" said Rep. Richard Nugent, R-Fla.. "Do we ever … turn off the tap and say, 'Hold on a second, you're not meeting the goals?' "

Rep. Jackie Speier, D-Calif., agreed. "How do we put in place some sort of governance of these efforts so that when they are failing, we just fess up to it and pull that plug?" she said.

Andrew Tilghman is the executive editor for Military Times. He is a former Military Times Pentagon reporter and served as a Middle East correspondent for the Stars and Stripes. Before covering the military, he worked as a reporter for the Houston Chronicle in Texas, the Albany Times Union in New York and The Associated Press in Milwaukee.