Inside a hospital tent in England on the night of June 5, Army Nurse Opal Grapes was relaxing after another long day of getting prepared for the invasion of Europe. By the time she arrived in England in the spring of 1944 there were already rumors that the invasion was coming soon.

As celebrations take place in France and around America honoring the men and women who took part in that mission on its 75th anniversary, there are fewer and fewer who remember it firsthand. Grapes, 98 and living in Houma, Louisiana, is one of five American D-Day survivors to share those recollections with Military Times.

“I just remember the night before, a group of nurses and I were sitting around talking and we heard the sky roaring with planes and so we knew that D-Day was happening,” Grapes said.

RELATED

Grapes was right. The planes she heard marked the beginning of Operation Overlord, the invasion of Normandy.

“I wasn’t afraid, I just knew it was happening,” Grapes said. “I certainly knew we had to kick the Germans out.”

A retired Army Nurse, Grapes remembered the invasion from the moment the first planes flew across the English channel to mid afternoon.

By then her hospital was already filled with hundreds of casualties.

♦ The Sky ♦

On June 6, 1944, in the dark hours just after midnight, over 13,000 American paratroopers were poised to spearhead the largest military invasion in history. Standing by anxiously waiting inside twin-engine C-47 Skytrains, the paratroopers of the 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions were determined to accomplish one of the most critical and risky missions ever undertaken. One, if successful, that would forever change the history of the world.

Still in his early twenties, 1st Lt. Gerald “Bud” Berry, assigned to the 91st Squadron of the 439th Troop Carrier Group was among them.

“We carried the 101st Airborne E Company and D Company and they jumped from our airplanes,” Berry said.

Flying co-pilot to his squadron commander, Berry recalled that the mission was going smoothly up until they hit an enormous cloud bank over the coast of France which made the already near impossible flight optics of the mission even worse.

“You can’t tell anywhere about where you are at night, whether you’re at the dropzone or over the dropzone,” Berry said.

As the hundreds of other aircrews entered the cloud bank that would soon surround them, some pilots started to either gain or lose altitude in hopes to quickly bypass the storm before they made it to the dropzone. Berry, however, decided that it was best to stay on course in hopes that the skies would soon clear.

Berry’s swift decision worked out, although when the clouds finally cleared there was no time to spare. They were only about two minutes away from their designated dropzone.

In the midst of hellish German anti-aircraft fire, Berry had to instantly adapt to his surroundings before signaling to the paratroopers behind him when it was time to jump.

“The only thing we were concerned with was the troopers and how they were making it off,” Berry said.

After releasing all the men in the back of his plane, Berry was headed back to England along with the rest of the pilots that made it through that unbelievable flight to await further orders.

♦ Omaha Beach ♦

About the same time as Berry’s wheels were touching down in England, 19-year-old Staff Sgt. Harley Reynolds was among the first Americans landing on Omaha Beach.

“All we could do is guess at what it could be like,” Reynolds said.

Reynolds, from St. Charles, Virginia, served as a machine gun section leader assigned to company B; 16th Infantry Regiment, First Infantry Division, during the D-Day invasion.

Although their mission that day was tremendous their orders were straightforward.

“Get ashore and get as far inland as we could,” Reynolds said.

Reynolds said that because of the storm that morning, many landing craft were blown off course, adding to the chaos. His landing craft was one of the few that made it all the way to the beach and he was able to get out without having to go in the water.

“That doesn’t mean that it was easy,” Reynolds said.

As they hit the beach, the men were first held up by an impenetrable barbed wire fence. Laying on the beach taking cover from relentless enemy fire for about an hour, Reynolds and his men held tight waiting for someone to come blow it.

Suddenly, a man appeared next to Reynolds with a bangalore torpedo, a device that was designed to breach barbed wire. Just as the man finished detonating the bangalore, the man was hit and died instantly.

As soon as the barbed wire was blown, Reynolds instantly began his advance, making him the first man to clear the barbed wire on the beach.

Although he finally made it through the wire, Reynolds said that due to all the other obstacles and land mines planted throughout the beach, progress was extremely slow, and almost stagnant at times.

“I had one man go around me and try to get in front of me because he thought I was going too slow. He only got 10 or 12 steps in front of me before he stepped on a mine and blew off his left heel,” Reynolds said.

By the end of the day, Reynolds and his men had fought their way a few hundred yards inland, exhausted, they slept wherever they stopped.

♦ Utah Beach ♦

While Reynolds and the rest of the First Infantry division pushed inland at Omaha Beach, to the west, Gunners Mate 3rd Class Tolley Fletcher remembers standing by as the hundreds of LCVPs lined up for the assault on Utah Beach

Aboard the wooden submarine chaser USS SC-1301 which is apart of what is known as the “Splinter Fleet” Fletcher spent his day protecting LCVPs from potential submarine attacks while they rushed ashore.

“They used us to escort the LCVPs into Utah Beach,” Fletcher said.

Along with the other 150,000 troops taking part in the invasion, Fletcher already had been ready for this moment for over 24 hours. They originally tried to cross on June 5th, but because of the weather the waters were too rough so the invasion was postponed.

“It changed the whole world just about, since then the whole United States has changed,” Fletcher said.

Fletcher, only 19 at the time, didn’t see any infamous German U-Boats that day. But he did see the entire day unfold before his eyes.

“As we got in further the water was already full of bodies,” he said.

♦ The Dead ♦

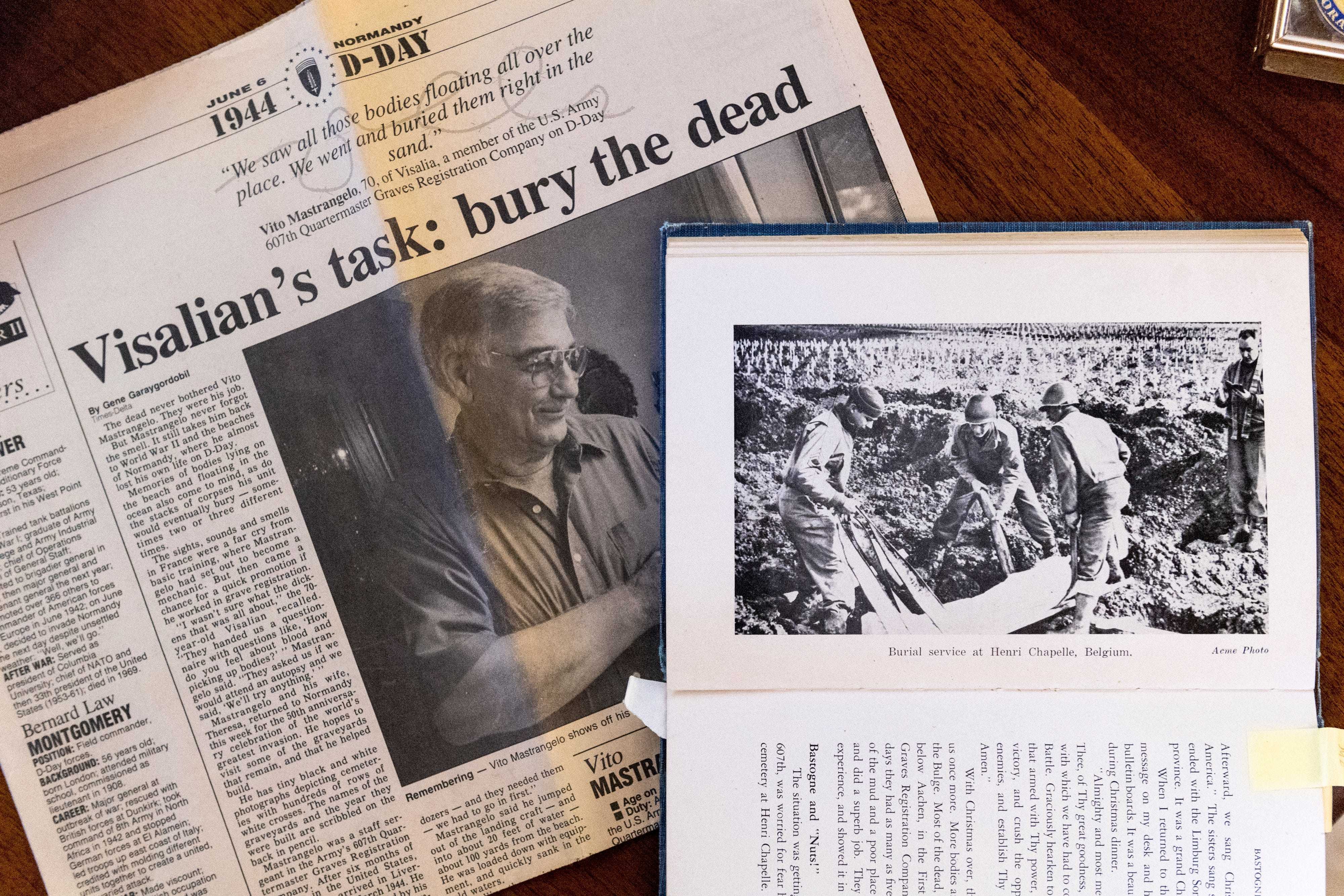

Technical Sergeant Vito Mastrangelo, just 20, was in charge of taking care of those bodies as a member of the 607th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company. He wasn’t supposed to be landing until the following day, but due to the chaos and tremendous number of casualties, he was ordered to start tending to the thousands of bodies that were already scattered all over the water and sand. He recalls that even by the time he landed at Omaha Beach the rotting stench of death had already filled the air.

Mastrangelo spent his first night in Normandy on the beach cold and wet inside a German trench. When he woke up the next day he and his company went to work burying over 400 young men on the beach right next to the waters edge.

“I still think about those boys everyday," Mastrangelo said.

“I happened to be in church the other day and the Father was talking about Veterans Day, and I stood up and I said, ‘Father John, I am one of those vets of D-Day and there is not a day that passes that I don’t think about those boys,’” Mastrangelo said.

According to Mastrangelo, as the Allied forces kept pushing further inland the men originally buried on the beach were dug back up and moved to another cemetery on top of the bluff in the days that followed. By the time they were finished, Mastrangelo says that he and his company had buried over 18,000 young men on top of the bluff.

The cemetery Mastrangelo left atop of the bluff at Omaha Beach is a lot different than what it looks like today. Since many of the families wanted the remains of their loved ones brought home, just over 9,000 out of the original 18,000 are still buried there.

Mastrangelo said that years later sometimes he’d be outside and smell something dead. The first few times it happened he thought it was a dead animal, only later did he realize it was an olfactory memory of the young men he buried.

Like many Veterans, he never talked about what he did during the war. He didn’t start opening up about his experiences until he revisited the Normandy beaches on D-Day’s 50th anniversary.

♦ Today ♦

To commemorate the invasion’s 75th anniversary, some of these D-Day veterans plan to attend ceremonies to honor the sacrifices on that day. For others, it will be just another day of remembering.

“A lot of people come up to me and ask, ‘Were you there?' and I say, ‘I’m still there,’" Mastrangelo said.

For Berry the day is “all in the past” but he still recalls just how important that day was.

Just shy of 100 years old, Grapes, the nurse, is proud of how so many young people joined together to drive the Germans out of Europe. She still remembers everything from that day and how thousands gave or risked their lives for other people that they had never met.

“I’m so honored that I could be there and take care of the brave men who fought,” Grapes said.

Fletcher, now 94, will be a guest speaker at the National World War II Museum in New Orleans looking back on the historical importance of D-Day. Like Grapes, Fletcher wants people to remember one thing.

“How important it is that people are willing to give their lives to protect other people,” Fletcher said.

Reynolds, also now 94, will be the guest of honor at a D-Day commemoration being held at MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa, Florida.

“I feel damn lucky," he said. “I’m not religious but I could not deny having a little divine help because I made it through and a lot of people didn’t.”

Image 0 of 24