WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. — Over the last eight years, Christopher Simmons has turned his classroom at Meadowlark Middle School into a safe space for students with special needs.

“If they need anything,” he said one afternoon after the last of his students filtered out of his room, “that door is open.”

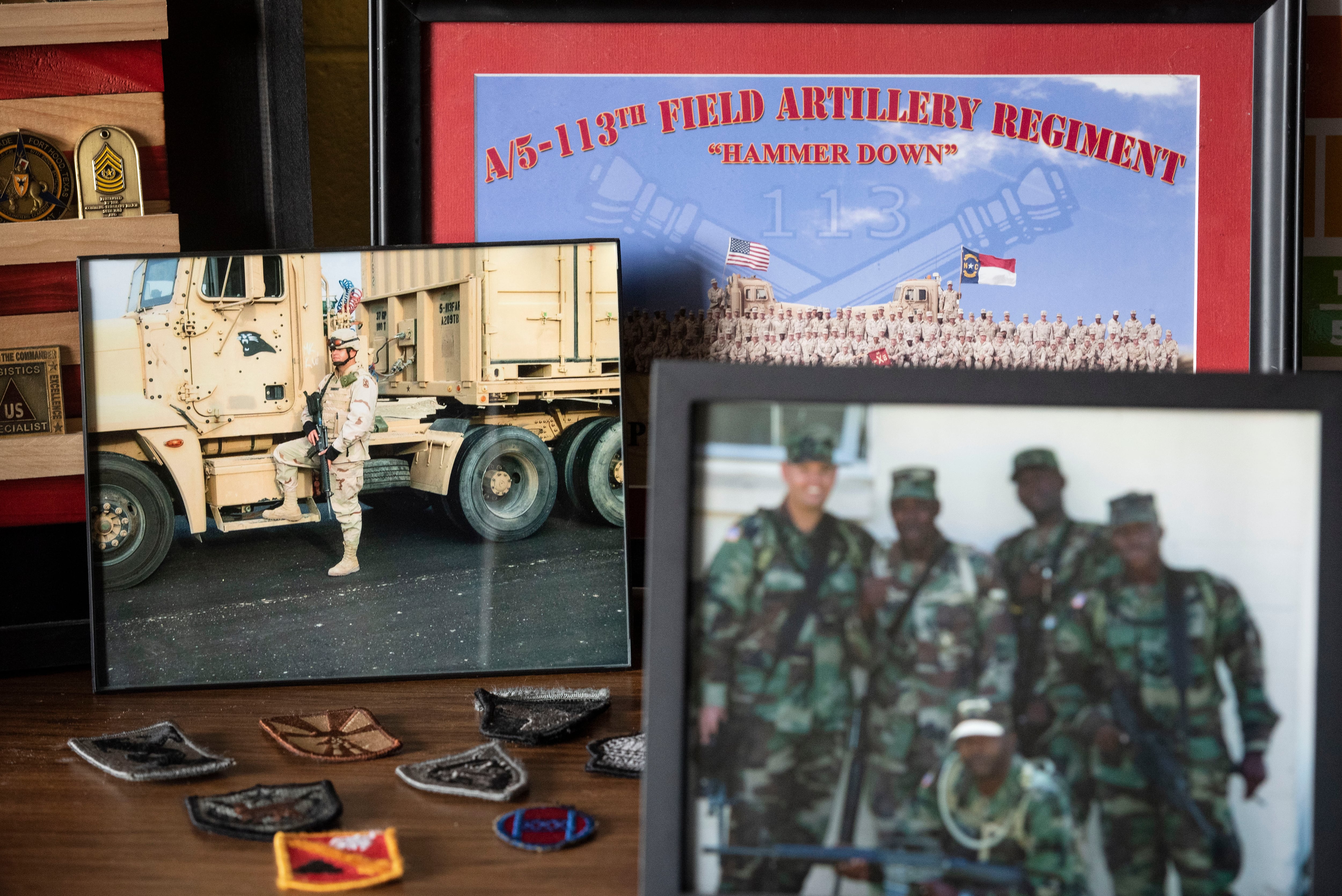

A bright room decorated with posters on decimals and percentages and an American flag, Room 602 has also been a sanctuary for Simmons after his years of feeling adrift following a forced medical retirement from the Army.

Helping a student work out a math problem, Simmons feels a world away from Fallujah, Mosul, Baghdad, and all of the trauma and ensuing depression that came from serving in a war zone, where he was always on alert and always fearful of being killed or having to kill.

Simmons credits the Army with helping him become a better teacher. He doesn’t give up on students, just as his drill sergeants never gave up on him.

But his military service, what he once considered his life’s calling, no longer defines him.

Something else does. Those kids.

“I’m not a soldier anymore,” Simmons said. “I’m a teacher.”

Getting to that point, where he could freely shed the image of himself as a soldier and embrace being a teacher has been its own hard-fought battle, one that nearly broke him.

A natural progression

Simmons was born in Lumberton, then moved with his family to Florida.

His struggles in school started early.

“I couldn’t grasp language. I couldn’t read,” Simmons said.

In those early days of special education, his parents and teachers collaborated on ways to help him with what he guesses would today be labeled as dyslexia.

Simmons took speech therapy, went to after-school tutoring and was retained a grade by his parents.

Even after he began to grasp concepts and make good grades, he couldn’t shake the notion that he was not as smart as other kids.

One day, he joined the Boy Scouts. Something clicked. He felt comfortable and confident, feelings he never experienced in the classroom.

“The organization, the structure,” Simmons said. “I got it.”

The military seemed a natural progression. He dropped out of high school, got his equivalency diploma and joined the Army in 1989.

When he put on the uniform, all those lingering feelings of inadequacy, of being the kid who needed special help with his school work, dissipated.

RELATED

The way the Army taught things, breaking down difficult concepts and tasks, clicked with him. He passed tests with the highest marks.

“You’re taught step 1, step 2, step 3 in such a way that you can’t fail, and I started to excel in that,” he said. “That’s when I realized, ‘I’m capable.’”

Simmons served in the infantry in Operation Desert Storm from December 1990 through the end of May 1991.

A few years later, he went to UNC Wilmington, then joined the National Guard as a way to supplement his salary while teaching in Davie County Schools. During his stint in Davie County, the United States entered wars with Iraq and Afghanistan.

In the early days of those conflicts, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld decided to increase the number of National Guard units deployed to both theaters. Simmons’ unit was called, so he left the classroom to serve in field artillery, supporting troops in a “beans and bullets” mission.

“We’d take supplies and guns from Kuwait to Mosul, Tikrit and Balad and other [forward operating bases] around Baghdad,” Simmons said. “It was one of the most dangerous jobs over there.”

On his first mission, a man with an AK-47 stepped out of his Toyota truck and opened fire.

There was no damage to the truck Simmons was riding in, but he was rattled.

“And that was my introduction to driving the roads in Iraq,” he said.

Another time, his convoy passed what appeared from a distance to be a man sitting on the side of the road dressed in traditional clothing.

It was actually a camouflaged 55-gallon drum filled with fuel that detonated as the convoy passed. Flames soon engulfed the fuel-covered vehicles. Luckily, no one was injured.

“Those that were trying to kill us were constantly studying us,” Simmons said.

In all, Simmons estimates that his transportation unit was hit more than 200 times in his first tour.

Within three months after his tour ended, Simmons was back in the classroom, a head-spinning transition that he likened to going from 120 to 20 miles per hour.

“I’m in Iraq doing my thing and three months later, I’m teaching elementary kids,” Simmons said. “I had no time to process the trauma I had encountered, no time to re-adjust to anything. It messes with your mind.”

After several months back in the classroom, one of his students became particularly disruptive. It triggered something in Simmons, and he walked out of the classroom, realizing he was not in the right mindset to be with children. He soon resigned and volunteered to go back to Iraq.

He was done with education.

“I was going to be a soldier until I was 55,” he said.

Back in the classroom

Unresolved trauma, which led to depression, laid waste to that plan. Simmons fell into a dark place.

At one point, he tried to kill himself, something he is willing to share because “people need to talk about about this kind of stuff.”

The Army forced him to medically retire after a series of tests indicated he was not fit for duty.

RELATED

Reeling but determined to get better, he sought counseling at a Veterans Affair Hospital and began restoring his mental health.

One problem remained. He needed more money. His military retirement wasn’t enough to pay the bills.

One day out of the blue, he got an email from a principal in Iredell County who needed an exceptional children’s teacher. Simmons took the job out of desperation.

“I took it out of necessity, not desire,” Simmons said.

As he readjusted to being in the classroom, something magical started to happen. He began to see himself in these students, kids with learning disabilities who needed extra guidance, instruction and someone in their corner telling them they are important and capable.

Simmons came to Meadowlark in 2015, teaching math to students with special needs in grades 6-8. He leads the school’s Students Against Violence Everywhere, or SAVE, Promise Club, and he and his kids take care of the American flag outside of the school each day.

Principal Matt Dixson said Simmons always puts kids first.

“Anything to reach or benefit the kids, he’s willing to do,” Dixson said.

As for the kids?

“He’s fantastic and cool,” one of them said recently as he was exiting Room 602.

Simmons sets high expectations for his students. He’s relentless in making sure they reach them.

“We’re not going to settle on what a test says, or what a data point says,” Simmons said. “We’re just going to work hard and we’ll push ourselves until we can find who we truly are.”

For as much as Simmons has given his students, what they’ve radiated back to him is something far greater.

When a struggling student understands a multiplication problem, when he’s invited to a former student’s graduation or gets a card from a grateful parent that reads, “Hey, my kids love you,” Simmons realizes that he has found his purpose.

Not in uniform, but the classroom.

“I realize,” he said, “there’s no greater job than helping these kids believe in themselves.”

If you or a loved one is experiencing thoughts of self-harm or suicide, you can confidentially seek assistance via the Military/Veterans Crisis Line by calling 988 and dialing 1, via text at 838255 or chat at http://VeteransCrisisLine.net.