Americans, federal employees and politicians know budget shutdowns to be a near annual fixture of governance.

The threat of one, at least, has become standard operating procedure, and agencies by now are used to expending more effort than they’d like planning for a lapse in appropriations, whether it happens or not. Data from 2013 shows at least $2 billion worth of work-hours were lost during a two-week shutdown.

To prepare for what is often an up-to-the minute change, agencies are expected by the White House to have shutdown contingency plans at the ready that are updated regularly, not just when a funding gap seems imminent. Even short-term continuing resolutions require agencies to divert attention from their normal business and have a predetermination of what, and who, is affected.

“It requires a lot of manpower and hours and time to actually prepare for either the possibility of a shutdown or the likelihood, based on recent historical experience of a CR,” said Andrew Lautz, a senior analyst at the Bipartisan Policy Center. “There’s an opportunity cost to that, too, in the weeks and months leading up to Oct. 1.”

That said, federal agencies have good practice operating under CRs at this point, Lautz added, and so the planning that goes into this time of year is not paranoia, but preparedness.

RELATED

For one, the more extreme shutdowns since the 1990s have lasted several weeks and were damaging to the federal workforce, the contracting industry and the taxpayer, numerous watchdog reports have said.

Yet for those who remember, there was a time when shutdowns spanned less than a week, sometimes just a few hours, if they even happened at all.

And when it did happen, there was still political infighting and dogma underlying it as there is today, though now it feels more poignant, experts said.

“In my whole career, most of the things that happened in the government were essentially uncomplicated,” said Reg Jones, a retirement expert for Federal Times and assistant director of the U.S. Office of Personnel Management from 1979 to 1995. “There were debates at the Bureau of the Budget ... trying to balance out income versus outgo, and so forth. Of course, you’ll have to remember, too, that in those older days, many in the House and the Senate were overwhelmingly run by one party.”

Today, in a divided government with Republicans controlling the House against a democratic executive branch, that balance point teeters back and forth, Jones said, “allowing for more carrying on and foolishness.”

“The real question is why most Republicans will not jettison a hard line from the Freedom Caucus that almost all Republicans know will hurt the party?” said Roy Meyers, a professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. “And why won’t they deal with Democrats to pass a bipartisan appropriations bill? If policy was the only issue, rather than partisan conflict, I think there’d be a lot of Republicans that would be willing to deal.”

And the “must-pass” nature of fiscal policy can make it even more difficult for budgets to be reconciled in a divided government, wrote Molly Reynolds of the Brookings Institute in 2019.

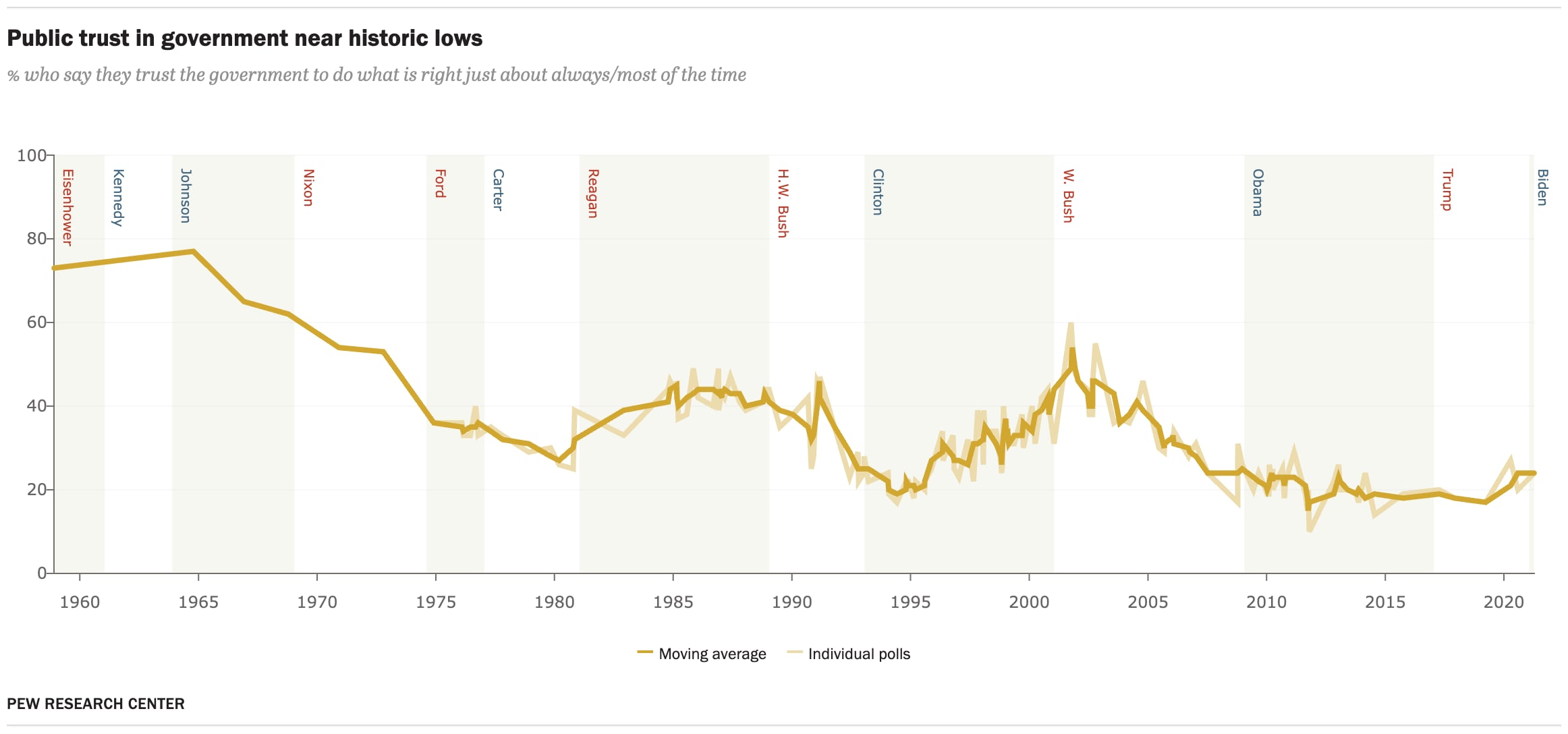

Meanwhile, the Pew Research Center shows in a September report that public trust in government has fallen once again to near-record lows. Further, while public views of lawmakers have historically been poor,” the share of Americans giving Congress an unfavorable rating is now among the highest in nearly four decades of polling,” according to the report.

The other historical difference accounting for perhaps a “new age” of shutdowns is the major legislative reforms that shaped the budget process, and congressional proceedings, that hum in Congress today.

Generally, prior to 1980, the government continued operations through funding lapses, according to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. It found that since 1981, 10 funding gaps of three days or fewer have occurred.

“[Congress] just kept appropriating possibly year-round, and there was no schedule for doing it, and so you didn’t really have to worry about government shutdowns,” said Carl Cavalli, a political science professor at the University of North Georgia. “There may have been arguments over individual appropriations bills and things like that, but you didn’t have this everything coming to a head every September and October like you do now.”

Begging the question: how did we get here?

Congress changed the budget process in the 1970s with the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act and other reforms that added structure, deadlines and lines of authority over the federal purse. It established the House and Senate budget committees and the Congressional Budget Office, which added organization but also complexity and urgency.

“Those rule changes, plus the growing power of the Republican Party, which means the two parties are more evenly divided and much more likely to trade off control every now and then, is why we almost never finish the budget process on time [nowadays],” Cavalli said.

President Jimmy Carter’s attorney general also had a lot to do with the way the executive branch responds to Congress’ inability to pass a budget.

“You have asked my opinion concerning the scope of currently existing legal and constitutional authorities for the continuance of government functions during a temporary lapse in appropriations, such as the government sustained on Oct. 1, 1980,” Benjamin Civiletti wrote to his president three months later.

The conclusion he came to was agencies could avoid spending money they didn’t have and running afoul of the Antideficiency Act by suspending agency operations until appropriations are made. He was careful to carve out an exception for agency functions that affect “the safety of human life or the protection of property,” offering a yardstick for deciding which agency employees are considered “essential” during a lapse.

Today, that decisionmaking is still a part of agencies’ contingency plans on file with the Office of Management and Budget.

“What happens is that the essential things that are necessary for the government to continue in operation will continue,” said Jones. “They may be restricted. They may be minimal, but they will be there because there’s no way they can’t be there. At the end, after all the brouhaha ... it all goes back essentially to where it was, but at an extreme cost.”

Molly Weisner is a staff reporter for Federal Times where she covers labor, policy and contracting pertaining to the government workforce. She made previous stops at USA Today and McClatchy as a digital producer, and worked at The New York Times as a copy editor. Molly majored in journalism at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.