SEOUL, South Korea — For all its bluster and over-the-top propaganda, North Korea often does just what it says it will do when it comes to its weapons development.

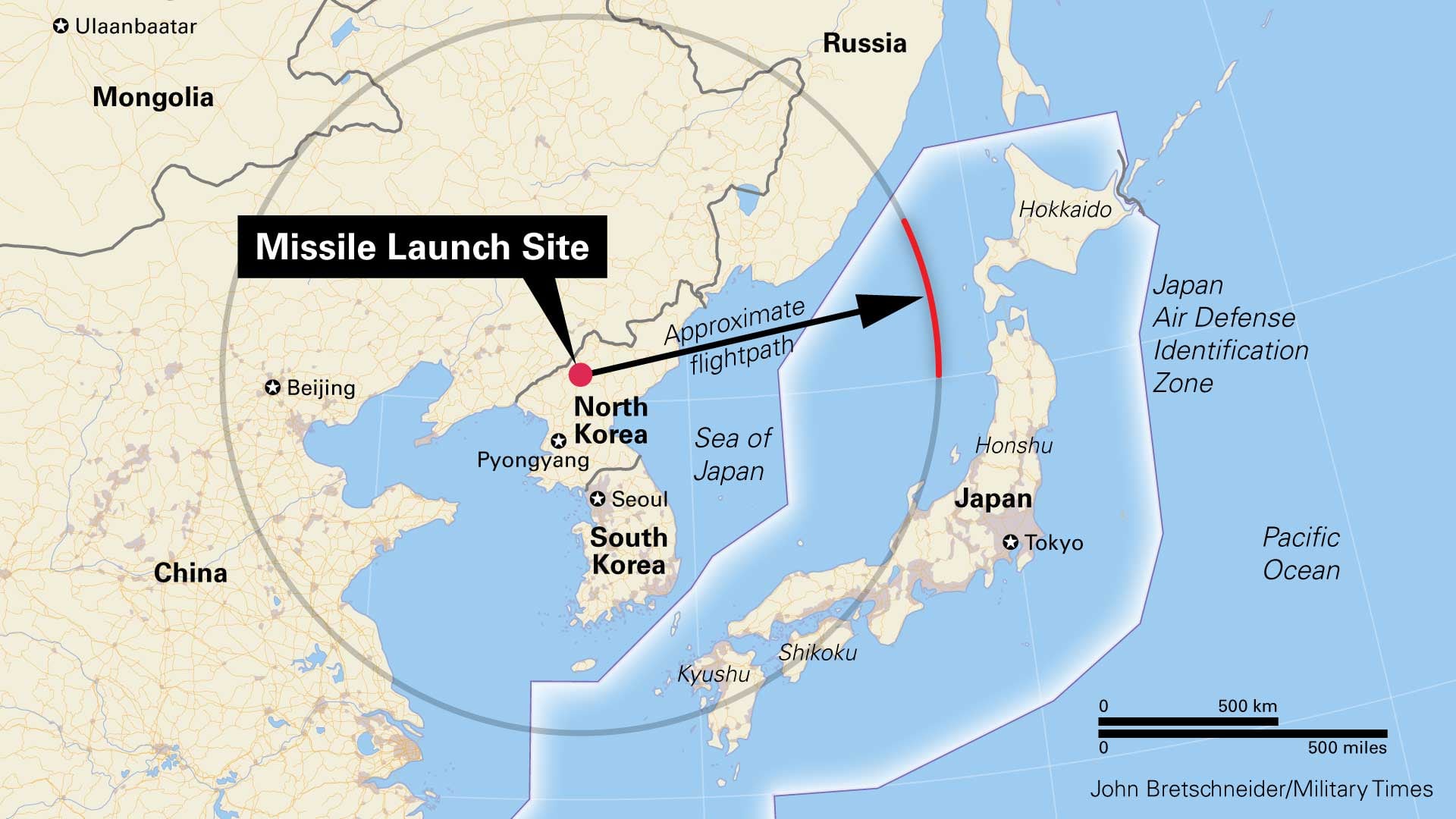

So it goes with its lightning-quick push to perfect an intercontinental ballistic missile. The clear message after Friday’s late-night test, the second in a month of a missile that may be able to reach most of the U.S. mainland: Get used to this — it’s the new normal.

So what exactly does that mean?

From the West’s point of view, it portends more and scarier missile and nuclear tests, each one more powerful than the last; a dogged determination by the North to ignore, as it has for decades, financial sanctions and other outside pressure, including a slightly more forceful clampdown from its biggest enabler, China; and an increasing likelihood that a determined, unchecked North Korea will soon turn its rhetoric about being capable of nuking America’s heartland into a reality.

All this is meant to force the United States to accept terms that Pyongyang favors: a formal end to the Korean War that would remove U.S. forces from the Korean Peninsula, weaken ties between Seoul and Washington, and make it much more likely that the North’s ultimate dream of a Korea united under its rule comes true.

Outsiders have long dismissed or ignored North Korea’s atomic boasts and propaganda, even as they’ve failed through sanctions, threats and isolation to hinder the North’s progress. It remains to be seen whether an effort led by a Trump administration distracted by political infighting can rise to the most serious challenge yet in what has been a decades-long nuclear standoff.

To see exactly what North Korea is aiming for, just read its propaganda.

The North promised a stream of missile “gift packages” for the United States after its first ICBM test on July 4. Then on Saturday, hours after its second test of the Hwasong-14, the country’s leader, Kim Jong Un, was quoted as saying by the North’s official Korean Central News Agency that “the U.S. trumpeting about war and extreme sanctions and threat against the (North) only emboldens the latter and offers a better excuse for its access to nukes.”

Friday’s test “is meant to send a grave warning to the U.S.,” Kim said, and “make the policy-makers of the U.S. properly understand that the U.S., an aggression-minded state, would not go scot-free if it dares provoke the” North.

That does not mean North Korea is planning to attack the United States with a nuclear missile. The country’s leadership values its survival above everything else, including the welfare of its people. North Korea’s huge artillery and missile armament along the North-South border could do serious damage to Seoul, but such an attack would spell the end of Pyongyang because of Washington’s massive weapons advantage. Nor is the North quite there militarily. It must still prove that its ICBMs can navigate the multitude of technical hurdles needed to accurately strike a faraway target.

Each new test, however, makes that more likely.

Having a working “nuclear strategic force” would also allow the North to introduce doubt into the U.S.-South Korea alliance. If fighting broke out between the rival Koreas, the argument goes, would Washington really rush in knowing that Pyongyang could hit the U.S. heartland with its nukes?

The latest test also does something that North Korea strives for in every word of its propaganda: It bolsters the dignity of the proud, authoritarian state, which has long seen itself as surrounded by hostile nations bent on its destruction. How many Third World U.S. enemies, after all, have built ICBM programs?

The message is as much for the elite in Pyongyang as for the North’s enemies, intended to solidify support for a leader who, despite massive external pressure, can stand up to the superpowers threatening his people.

Unless Seoul, Washington and their partners can find a way to stop the North, the near future looks pretty clear.

“More tests are needed to assess and validate the reliability of the Hwasong-14, so North Korea is sure to follow this launch with many more,” missile expert Michael Elleman wrote on the 38 North website after Friday’s launch.

More tests. More instability. More pressure to pursue indigenous nuclear programs among North Korea’s other presumed targets, Seoul and Tokyo, as they lose faith in the U.S. “nuclear umbrella.” And more possibility that a miscalculation in one of the world’s most heavily armed regions could lead to fighting.

That’s the new normal.

Foster Klug is AP’s Seoul bureau chief and has covered the Koreas since 2005.