BEIRUT — In a corner of northwestern Syria packed with nearly 3 million people, the government and its opponents are preparing for a final, bloody showdown.

The campaign for Idlib, the opposition’s only remaining stronghold in the country and now a refuge for over a million displaced Syrians, is likely to be the last major theater of battle after seven years of brutal civil war.

It is also potentially the most dangerous.

The U.N. and aid workers are bracing for disaster, warning that up to 800,000 people are in danger of renewed displacement if a government offensive gets underway. A massive military buildup in nearby areas suggests an assault — at least to regain parts of the province — may be imminent.

Turkey, which backs the rebels in Idlib, has warned against a military solution and is reportedly negotiating with Russia in an effort to avoid a full-scale offensive.

Concern is mounting meanwhile over the potential use of chemical weapons, and the Russian navy is building up its presence in the Mediterranean Sea.

Here's a look at what lies ahead for Idlib:

THE OPPOSITION’S LAST REFUGE

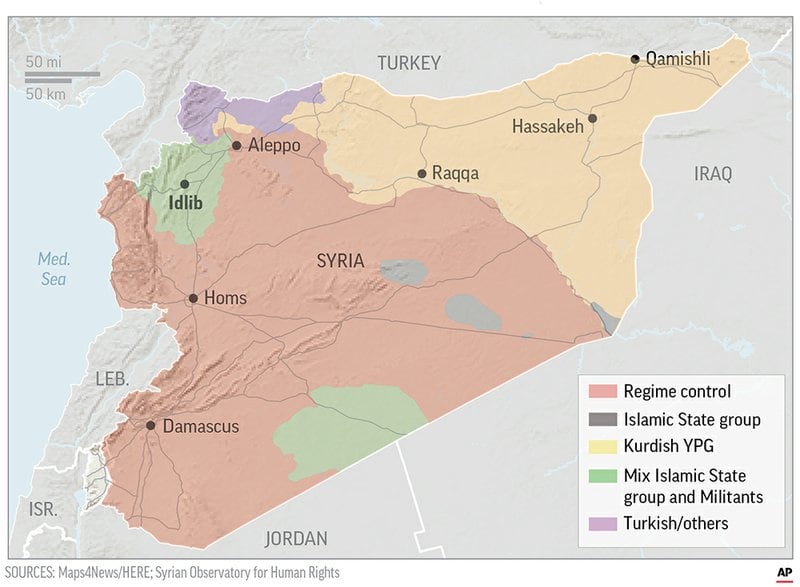

After seven years of war, President Bashar Assad has largely quashed the popular revolt that erupted against his family's decades-long rule in 2011, which was inspired by the Arab Spring protests that swept the region that year.

Idlib now amounts to the last refuge for the opposition, as well as the al-Qaida-linked insurgents that have fought alongside it.

President Bashar Assad is determined to retake Idlib, and has vowed to eventually bring all of Syria back under his government's control.

At one point, the opposition controlled parts of Syria's largest cities and most of the territory around Damascus, the capital. But Russia launched an air campaign in support of Assad in 2015, and Iran has sent thousands of military advisers and allied militiamen to aid his forces. In the last year alone, the government has forced its opponents out of Damascus, Homs, Daraa, and Quneitra, four provinces and cities that were longtime opposition strongholds.

As government forces advanced, they offered residents and one-time opponents the choice either to reconcile with Assad's rule or board buses for Idlib, where al-Qaida-linked groups have eclipsed the moderate opposition.

Tens of thousands of people chose to leave to Idlib, fearing they could be face imprisonment, forced conscription, or worse at the hands of government forces.

Now they have nowhere left to turn, after other opposition pockets have collapsed, and Turkey has largely sealed its borders to new refugees.

THE CHEMICAL WEAPONS FACTOR

The U.S. State Department has said it will hold Moscow, an ally of Damascus, responsible if government forces use chemical weapons in the battle for Idlib.

U.N. investigators have already attributed several chemical attacks in Syria to government forces, including one attack using the nerve agent Sarin gas against the Idlib town of Khan Sheikhoun in April 2017.

That attack prompted the U.S. to carry out a rare strike against a Syrian military installation. In April, the U.S., France and Britain launched punitive strikes after a chlorine gas attack on a suburb of Damascus then held by the opposition. The U.S. also holds the government responsible for a Sarin gas attack that may have killed over 1,000 people in August 2013 in the Ghouta suburbs of Damascus.

Syria's government denies ever using chemical weapons and says it disposed of its stockpiles under an agreement brokered by the U.S. and Russia after the 2013 Ghouta attack.

Chemical attacks have only accounted for a small fraction of the estimated 400,000 people killed in the civil war.

Now, Moscow and Damascus say the U.S. is planning to fabricate a chemical attack or encourage rebels to execute one, as a pretext to launch renewed strikes against Assad's forces. But there is scant evidence that rebels have used chemical weapons in the past, and the U.S. has shown little appetite for taking forceful military action against the government.

On Tuesday, U.S. Defense Secretary James Mattis said Washington was in "active" communication with Russia about preventing another chemical attack.

A CATASTROPHE IN THE MAKING

The U.N. says a battle for Idlib would cause a humanitarian catastrophe. With Turkey closing its borders to new refugees, it is unclear where civilians might go. Many are already living in camps in Idlib amid dire conditions, with 2 million in need of humanitarian aid.

The leaders of Russia, Iran, and Turkey are slated to meet next week in the northern Iranian city of Tabriz, where many are hoping for a deal to avert a calamitous battle over Idlib.

In the meantime, the government is amassing its forces around the province, and Russia has positioned at least 10 warships and two submarines off the coast, according to Russian media reports.

If a campaign does proceed against Idlib, it is likely to follow the formula set in previous battles. Russian and Syrian warplanes would launch wave after wave of devastating airstrikes, before government forces besiege towns and cities, forcing residents to surrender or starve.