WASHINGTON — America’s long-running reluctant relationship with the International Criminal Court came to a crashing halt on Monday as decades of U.S. suspicions about the tribunal and its global jurisdiction spilled into open hostility, amid threats of sanctions if it investigates U.S. troops in Afghanistan.

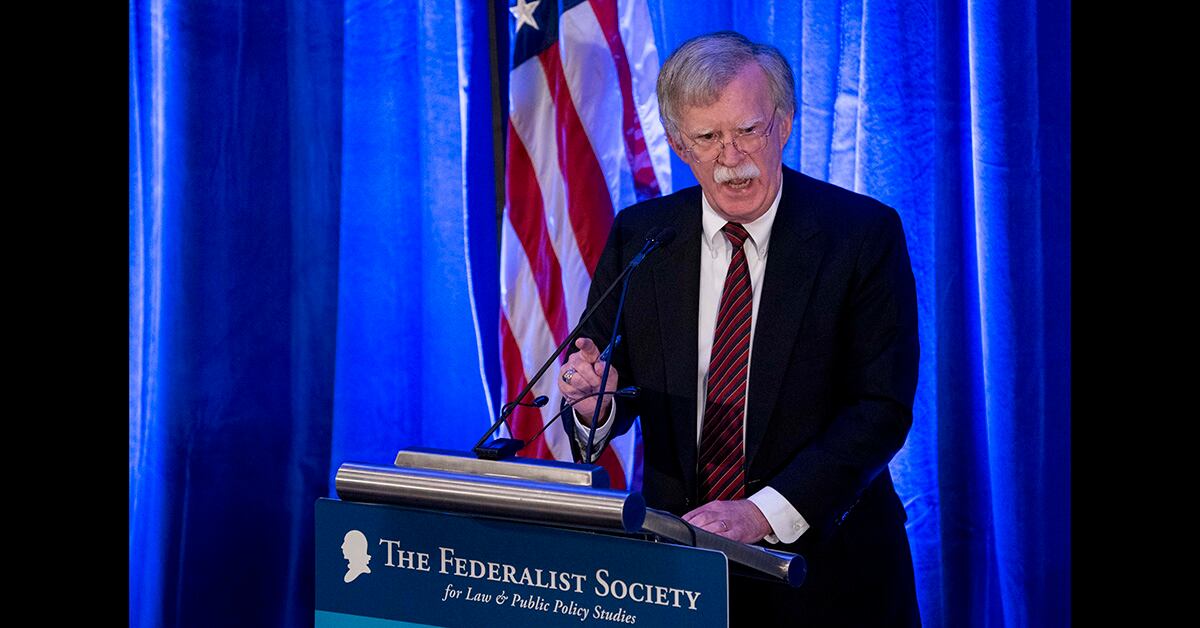

National security adviser John Bolton denounced the legitimacy of The Hague-based court, which was created in 2002 to prosecute war crimes and crimes of humanity and genocide in areas where perpetrators might not otherwise face justice. It has 123 state parties that recognize its jurisdiction.

Bolton’s speech, on the eve of the anniversary of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, came as an ICC judge was expected to soon announce a decision on a request from prosecutors to formally open an investigation into allegations of war crimes committed by Afghan national security forces, Taliban and Haqqani network militants, and U.S. forces and intelligence in Afghanistan since May 2003. The accusations against U.S. personnel include torture and illegal imprisonment.

RELATED

"The International Criminal Court unacceptably threatens American sovereignty and U.S. national security interests," Bolton told the Federalist Society, a conservative Washington-based think tank. Bolton also took aim at Palestinian efforts to press war crime charges against Israel for its policies in the West Bank, east Jerusalem and Gaza.

He said the U.S. would use "any means necessary" to protect Americans and citizens of allied countries, like Israel, "from unjust prosecution by this illegitimate court." The White House said that to the extent permitted by U.S. law, the Trump administration would ban ICC judges and prosecutors from entering the United States, sanction their funds in the U.S. financial system and prosecute them in the U.S. criminal system.

"We will not cooperate with the ICC," Bolton said, adding that "for all intents and purposes, the ICC is already dead to us."

It was an extraordinary rebuke decried by human rights groups who complained it was another Trump administration rollback of U.S. leadership in demanding accountability for gross abuses.

"Any U.S. action to scuttle ICC inquiries on Afghanistan and Palestine would demonstrate that the administration was more concerned with coddling serial rights abusers — and deflecting scrutiny of U.S. conduct in Afghanistan — than supporting impartial justice," said Human Rights Watch.

The American Civil Liberties Union, which represents several people who claim they were detained and tortured in Afghanistan from 2003 to 2008 and could be victims or witnesses in any ICC prosecution, said Bolton's threats were "straight out of an authoritarian playbook."

"This misguided and harmful policy will only further isolate the United States from its closest allies and give solace to war criminals and authoritarian regimes seeking to evade international accountability," the ACLU said.

The ICC did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Since its creation, the court has filed charges against dozens of suspects including former Libyan dictator Moammar Gadhafi, who was killed by rebels before he could be arrested, and Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, who is accused of charges including genocide in Darfur. Al-Bashir remains at large, as does Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony, who was among the first rebels charged by the court in 2005. The court has convicted just eight defendants.

The court has been hobbled by the refusal of the U.S., Russia, China and other major nations to join. Others have quit: Burundi and the Philippines, whose departure, announced earlier this year, takes effect next March.

The Clinton administration in 2000 signed the Rome Statute that created the ICC but had serious reservations about the scope of the court's jurisdiction and never submitted it for ratification to the Senate, where there was broad bipartisan opposition to what lawmakers saw as a threat to U.S. sovereignty.

When George W. Bush took office in 2001, his administration promoted and passed the American Service Members Protection Act, which sought to immunize U.S. troops from potential prosecution by the ICC. In 2002, Bolton, then a State Department official, traveled to New York to ceremonially "unsign" the Rome Statute at the United Nations.

Bush's first administration then embarked on a diplomatic drive to get countries who were members of the ICC to sign so-called Article 98 agreements that would bar those nations from prosecuting Americans before the court under penalty of sanctions. The administration was largely successful in its effort, getting more than 100 countries to sign the agreements. Some of those, however, have not been formally ratified.

In Bush's second term, the U.S. attitude toward the ICC shifted slightly as the world looked on in horror at genocide being committed in Sudan's western Darfur region. The administration did not oppose and offered limited assistance to an ICC investigation in Darfur.

The Obama administration expanded that cooperation, offering additional support to the ICC as it investigated the then-Uganda-based Lord’s Resistance Army and its top leadership, including Kony.

On Monday, Bolton effectively turned Washington's back on the court, accusing it of corruption and inefficiency. Above all, he took aim at the court's view that citizens of nonmember states are subject to its jurisdiction.

"The ICC is an unprecedented effort to vest power in a supranational body without the consent of either nation-states or the individuals over which it purports to exercise jurisdiction," Bolton said. "It certainly has no consent whatsoever from the United States."

Associated Press writer Mike Corder in The Hague, Netherlands.