BEIRUT — Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi sought to establish an Islamic “caliphate” across Syria and Iraq, but he might be remembered more as the ruthlessly calculating leader of the Islamic State group who brought terror to the heart of Europe and set up a short-lived organization so extreme that it was shunned even by al-Qaida.

With a $25 million U.S. bounty on his head, al-Baghdadi steered his chillingly violent but surprisingly disciplined followers into new territory by capitalizing on feelings of Sunni supremacy and disenfranchisement at a period of tumult after the Arab Spring.

One of the few senior ISIS commanders still at large, al-Baghdadi died Saturday when he detonated his suicide vest in a tunnel while being pursued by U.S. forces in Syria’s Idlib province, killing himself and three of his children, U.S. President Donald Trump announced Sunday. He was believed to be 48.

“He didn’t die a hero, he died a coward, crying, whimpering and screaming,” Trump said.

RELATED

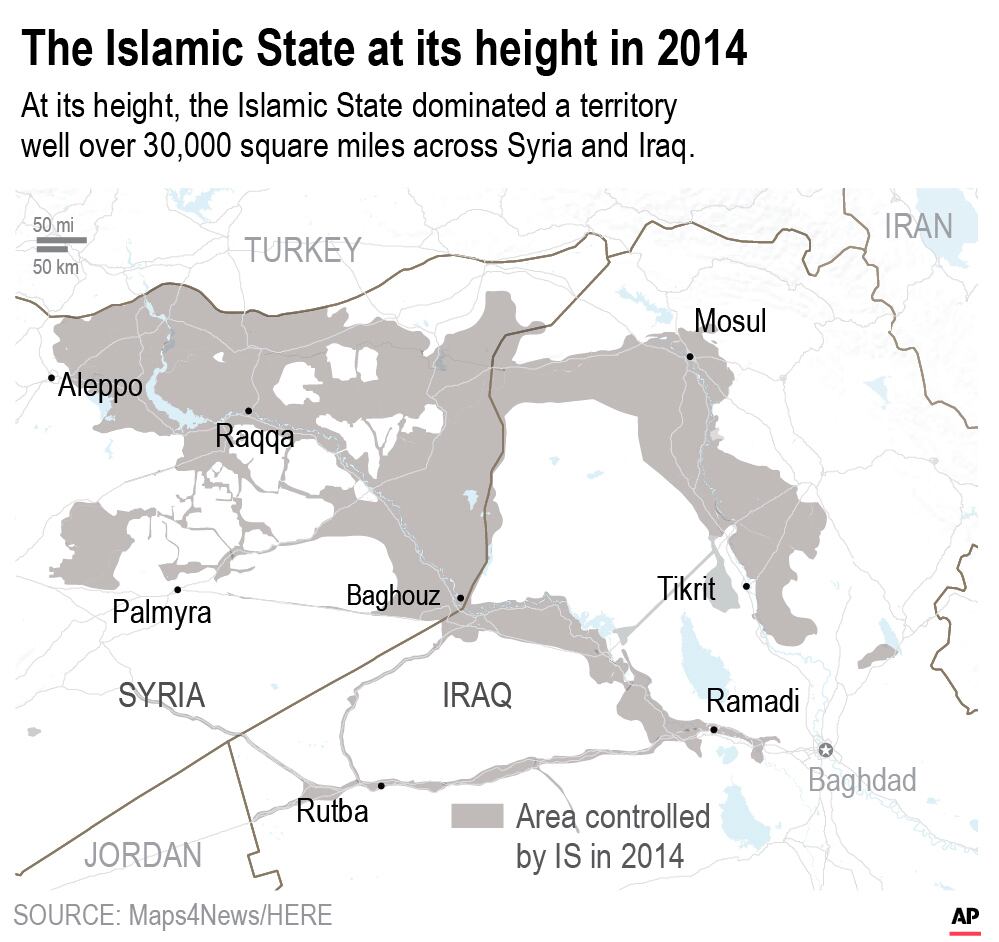

News of his death came five years after the Islamic State humiliated Iraq’s military by seizing nearly a third of the country. Steady battlefield losses in the last two years saw the group’s territory shrink from an area the size of Britain to a speck in the Euphrates River valley. In April, Kurdish-led forces backed by Washington declared the territorial defeat of IS after liberating the village of Baghouz in eastern Syria, the group’s last bastion.

Militants under al-Baghdadi’s command deftly exploited social media to tout the group’s military successes, document their mass slaughter, beheadings and stonings, and promote their cause to a global audience.

The impact of al-Baghdadi’s death on future attacks is unclear: The shadowy leader had been largely regarded as a figurehead of the global terror network and was described as “irrelevant” by a coalition spokesman in 2017. The group also has lost many of its senior commanders in airstrikes since 2015.

Al-Baghdadi was born as Ibrahim Awwad Ibrahim Ali al-Badri al-Samarrai in 1971 in Samarra, Iraq, about 95 kilometers (60 miles) north of Baghdad, according to a U.N. sanctions list.

A 2014 biography in online jihadi forums traced his lineage to the Prophet Muhammad’s Quraysh tribe. Its unconfirmed claims said al-Baghdadi earned a doctorate from Saddam University for Islamic Studies. It says he promoted the Salafi jihadi movement, which advocates “holy war” to bring about a strict version of Islamic law, or Shariah.

According to ISIS-affiliated websites, al-Baghdadi was detained by U.S. forces in Iraq in 2004 for his militant activity, although he was considered a civilian detainee. He was released 10 months later and joined the al-Qaida branch in Iraq of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi.

After Al-Zarqawi was killed by a U.S. airstrike in 2006, al-Baghdadi became a trusted aide to two senior figures, Abu Omar al-Baghdadi and Abu Ayyub al-Masri, assuming control of the group, known then as the Islamic State of Iraq.

The group, al-Qaida’s official franchise in Iraq, had been weakened by years of U.S. and Iraqi raids and the mobilization of Sunni fighters opposed to its extremist ideology. But al-Baghdadi deployed suicide attackers, car bombs and gunmen against Iraqi forces and Shiite civilians as the U.S. drew down its troops ahead of a 2011 withdrawal. Prison breaks bolstered his group’s ranks.

RELATED

Amid the uprising against President Bashar Assad in Syria, he sent comrades there to create a Sunni extremist group known as the Nusra Front, which more moderate Sunni rebels initially welcomed.

Over time, more of his fighters and possibly al-Baghdadi himself relocated to Syria, pursuing plans to restore a medieval Islamic state, or caliphate, spanning both Iraq and greater Syria. In April 2013, al-Baghdadi announced what amounted to a hostile takeover of the Nusra Front, merging it into a new group known as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. The move caught both the Nusra Front and al-Qaida’s central command off guard.

Nusra Front leader Abu Mohammad al-Golani refused to accept the takeover. Ayman al-Zawahri, al-Qaida’s top leader, ordered al-Baghdadi’s group abolished. Al-Baghdadi would not compromise, and al-Qaida eventually distanced itself, saying it had no connection to al-Baghdadi’s group.

It went on to take control of key cities such as Raqqa, Syria, and Fallujah, Iraq. Then came the June 2014 offensive that drew the U.S. back into Iraq: Al-Baghdadi’s militants and allied Sunni fighters seized Iraq’s second-largest city of Mosul and other Sunni-dominated communities. Government troops put up little resistance, and al-Baghdadi’s fighters posted videos of its forces killing captured Shiite troops.

The group announced its own state governed by Islamic law, with al-Baghdadi as “caliph.” Muslims worldwide were urged to pledge allegiance to him and the newly renamed Islamic State group. On June 29, 2014, a video emerged of a man purporting to be al-Baghdadi giving a sermon at a Mosul mosque.

President Barack Obama launched airstrikes against ISIS on Aug. 8 to safeguard U.S. interests after thousands of Iraqi Yazidis, followers of an ancient religion, were targeted by al-Baghdadi’s fighters. ISIS militants responded by beheading Western captives, starting with freelance American journalist James Foley, and posting their deeds in gruesome online videos.

The U.S. and Arab allies launched airstrikes in Syria to help U.S.-backed Kurdish fighters battle the group. ISIS militants turned outward, claiming the Nov. 13 attacks in Paris that killed 130 people and the March 22 attacks in Brussels that killed 32.

Iraqi officials said al-Baghdadi was wounded in an airstrike on Nov. 8, 2014, in Iraq’s Anbar province. Days later, an audio message purportedly from him urged followers to “explode the volcanoes of jihad everywhere.”

On April 30, 2019, he appeared in a video for the first time in five years, acknowledging defeat in the group’s last stronghold in Syria but vowing a “long battle” ahead. He claimed the Easter bombings in Sri Lanka that killed over 250 people were part of the battle that “will continue until doomsday.”

Schreck reported from Bangkok. Associated Press writer Maamoun Youssef in Cairo contributed.