On Jan. 6, 2021, myths about voter fraud in the 2020 presidential election drove supporters of former President Donald Trump to the U.S. Capitol, where they attempted to stop Congress from certifying the results. About one in six people charged for storming the Capitol that day had connections to the military.

That event and others like it have opened a flood of debate about veteran and military communities being targeted with disinformation and the rise of extremism among the ranks.

Consider how Jan. 6, 2021 is described: as the “Capitol riot” or “insurrection” by most Democrats and many independents and centrist Republicans, or a “peaceful protest” by GOP supporters of President Donald Trump, shows a deepening divide between the two main U.S. political parties – a gulf arguably widened and supercharged by political-party- and nation-state-sponsored disinformation, leaving disgruntled followers potentially vulnerable to extremist ideology.

As part of an 18-month project through a partnership between Military Times and Military Veterans in Journalism, we’ll be reporting about disinformation and extremism as the issues relate to veterans and military communities. To start, we’ve compiled a list of frequently asked questions about extremism and disinformation in the military we will update throughout the year.

If you have a tip or idea, please email us at MVJ-Tips@militarytimes.com.

What is disinformation?

To start with, in the broadest definition, disinformation is any false information that is created deliberately to mislead people. It’s often spread covertly with the intention of influencing public opinion or obscuring the truth, according to Merriam-Webster’s dictionary

U.S. government leaders have taken a more nuanced approach. The Department of Homeland Security says disinformation can be targeted toward an individual, social group, organization or country. It’s typically spread with malice or greed and in pursuit of political, social or financial agendas, according to the Anti-Defamation League. At the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Department of Defense said the most harmful disinformation is that which sows global mistrust and confusion.

This kind of disinformation can come in various forms and includes hoaxes, propaganda and spear phishing, according to the United Nations.

Another tool for spreading disinformation, known as synthetic media, is becoming more prolific following recent advances in artificial intelligence. Synthetic media refers to AI-created text, images and audio. One of the most notorious forms of synthetic media are deepfakes, images or videos in which the face of one person is overlaid onto another person, often in real time.

What is misinformation?

Among the slightly varying descriptions of disinformation from dictionaries, government agencies, nonprofits and international organizations, one key word is consistent: “deliberate.” The deliberate nature of disinformation is what differentiates it from misinformation.

Misinformation, while also false, is not shared with the intention of causing harm, DHS says. Or as the American Psychological Association put it, misinformation is getting the facts wrong.

How about the lesser-known term, malinformation?

Unlike both disinformation and misinformation, malinformation is based on fact. It’s true information that is used for harmful or manipulative purposes, according to DHS.

In many cases, malinformation refers to situations in which facts are used out of context, such as editing a video to remove key information. It can also refer to information that stems from the truth but has been exaggerated to mislead, the Government of Canada said in a recent report. For example, some alternative media sites that rely on outrage to generate views will distort headlines, a tactic known as “click-bait.”

Doxxing – the practice of publicly revealing someone’s private information without consent – also falls under the umbrella of malinformation, the Anti-Defamation League said.

Who is deploying disinformation?

A variety of sources from homegrown extremists to foreign adversaries create disinformation targeted toward the American public.

Disinformation is spread by foreign states, including Russia, China and Iran, as well as transnational criminal groups and human smuggling organizations. Other governments have accused the U.S. of spreading disinformation in their countries, too. China said earlier this year that the U.S. spread rumors about data security issues with the Chinese company TikTok in an effort to suppress foreign businesses.

The State Department works to counter disinformation from Russia, which creates and spreads false narratives in order to confuse people and advance the Kremlin’s policy goals, the agency said. Russia and other actors spread disinformation to exploit the American public, and they often target the country during national emergencies, according to DHS.

Particularly after disasters, disinformation spreaders use social media to deny the event ever happened or claim it’s a “false flag,” meaning a covert operation by authorities that frames someone else. One of the most recent examples of this came after a train carrying hazardous items derailed in Ohio, when conspiracy theories spread that the wreck was a planned, deliberate attack by the U.S. government.

Disinformation can also come from U.S. citizens. Alex Stamos, Facebook’s former security chief, went so far as to say in 2020 that “the future of disinformation is going to be domestic.”

So-called domestic disinformation, which comes from message boards, websites and social media accounts, is created by both far-left and far-right individuals. However, two recent studies from the University of North Carolina and New York University found it’s more often a right-wing phenomenon. This homegrown disinformation bubbles up from message boards and finds its way onto ideological websites and social media. Its consequences are sometimes deadly. The Center for Strategic and International Studies, or CSIS, reported there were a historically high number of far-left and far-right terrorist attacks in 2021, and far-right attacks were more lethal.

Elected officials also have participated in the spread of disinformation. The University of Oxford found that politicians running for office in 45 democracies, including the U.S., have shared false information to gain voter support.

What is extremism?

When officials talk about extremism in the military, they generally focus on extremism in terms of religious, political or social ideologies.

The Pentagon lists one broad definition of extremism in the Department of Defense Instruction 1325.06. The directive makes clear that the actions matter most, specifically, violent action: “Advocating or engaging in unlawful force, unlawful violence, or other illegal means to deprive individuals of their rights under the United States Constitution or the laws of the United States…” And also advocating, engaging in, supporting or encouraging things like subversion, sedition or unlawful discrimination.

Each branch develops its own policies to enforce the DoD’s top-down guidance.

However, anti-extremism watch groups and academia break down extremism into non-violent extremism and domestic violent extremism.

DHS and Federal Bureau of Investigation use the term domestic violent extremism to refer to domestic terrorism threats, or U.S.-based, non-foreign influenced actions “through unlawful acts of force or violence dangerous to human life.” There’s an emphasis here on the “action,” since harboring extreme or hateful opinions or ideology may be considered protected under the First Amendment’s freedom of speech. You can have a hateful thought or opinion, you can voice that thought or opinion, but you can’t perform a hateful act without legal consequences.

One report by the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), an academic research center, collected data on instances of extremism since World War II and defines non-violent extremism as “individuals who engage in illegal extremist activity short of violence or who belong to a violent extremist group but do not participate in violent activities.” Again, the key here isn’t simply having an extreme belief, but acting violently from or on behalf of that belief.

How widespread is extremism and disinformation among military communities?

The extent to which extremism has seeped into military and veteran communities is a contentious debate on Capitol Hill and around the country. The argument about whether it’s a problem has heightened since the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol, when some Trump supporters believed the election was stolen and sought to overturn his loss.

There’s a lack of data about the infiltration of extremism in the active-duty military, according to the Council on Foreign Relations, a bipartisan, nonprofit think tank. Experts generally agree that only a small number of service members have been involved in extremist activities, but some argue that even a tiny proportion could damage the military’s reputation and harm U.S. security.

There’s more data available about veterans’ adoption of extremist views, and research in this arena has increased in the past two years.

Here’s a snapshot of what the data says:

• Of the rioters in the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol, 17% were veterans, Harvard University found. The same study showed that nearly all participants in the siege that day had shared or received misinformation about the 2020 election on social media platforms.

• Veterans were responsible for 10% of all domestic terrorist attacks and plots between 2015 and 2021, according to the CSIS. Veterans make up about 5% of the overall adult population in the U.S., according to data from the Bureau of Labor and Statistics in May.

• Individuals with military backgrounds make up 15% of the cases in a database kept by the University of Maryland that tracks people who were driven by their extremist views to commit criminal offenses. Together, veterans and service members account for 6% of the U.S. population as of May.

• The University of Maryland’s data shows a “significant uptick” in the past five years of people with military backgrounds who have committed extremist offenses. From 1990 to 2010, an average of seven people with military histories were added to the database every year. That increased to 63 people per year from 2018 to 2022.

A brief history of violent military extremists

Acts of violent extremism aren’t new to the U.S. military. The DOD tried addressing tensions following the Civil Rights Movement in a policy in 1969, but incidents continued.

Then in the early 1980′s former Army Green Beret and retiree Frazier Glenn Miller started a white nationalist paramilitary group called the White Patriot Party in Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Miller’s recruits wore Battle Dress Uniforms with Confederate flag patches sewn onto the left shoulder. Miller had plans to start a race war and used active-duty soldiers to create a weapons cache. Federal agents infiltrated the group before a major catastrophic event.

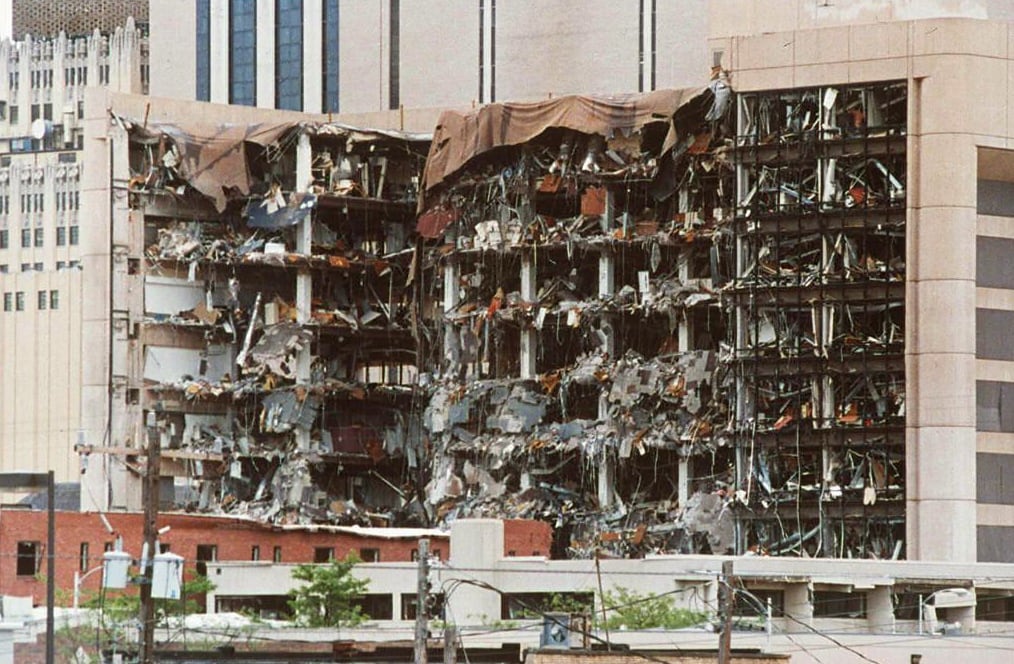

On April 19th, 1995 a former Army sergeant and special forces selection washout named Timothy McVeigh bombed a federal building in Oklahoma City killing 168 and injuring 684. That event is known as the deadliest domestic extremist act in the U.S. to date. Federal investigators later found McVeigh harbored antigovernment extremist ideology and even visited the Branch Davidian compound in Waco before the federal standoff there. The bombing in Oklahoma City prompted the Department of Defense’s next revision of its extremism policies.

Nidal Hasan’s name went down in infamy on November 5th, 2009. The then Army major opened fire on soldiers and civilians preparing to deploy at a readiness processing center on Fort Hood (now Fort Cavazos) near Killeen, Texas. Hasan killed 13 and injured more than 30 others. Prosecutors later argued in his trial that he had planned his attack to align with his views on Islamic extremism. He acted alone, but under the umbrella of a hateful or extremist ideology.

In terms of disinformation, one example occurred in March 2015, when residents in small towns across Texas began hearing whispers among social media networks that an annual military exercise known as “Jade Helm” was actually an attempt to suppress the locals, seize guns, and enforce martial law. The uproar kicked up enough of a ruckus that the governor enacted the Texas State Guard to oversee the national military’s operations. Years later, a former Central Intelligence Agency director revealed that Russia had launched a disinformation attack against the U.S. government.

What is Congress’ role in helping solve these problems?

Republicans and Democrats disagree about whether it’s necessary to address extremism among military and veteran communities.

In the wake of the Jan. 6 attack, Democrats urged the Pentagon to do more to counter extremism in the ranks, and they pushed the Department of Veterans Affairs to intervene when veterans show signs of being susceptible to recruitment by extremist groups.

Many Republicans, however, have attempted to halt Defense Department training aimed at countering extremism, criticizing it as a distraction from military preparedness and an effort to politicize the armed forces. Some Republicans have taken issue in particular with a daylong extremism “stand-down” in 2021, a military-wide training on the dangers of extremist ideology.

Lawmakers opposed to such training were able to cut seven of eight measures aimed at combatting domestic extremism from the annual defense policy bill, a legislative fight that is sure to come up in defense budget wrangling again this year.

This story was produced in partnership with Military Veterans in Journalism. Please send tips to MVJ-Tips@militarytimes.com.

Nikki Wentling is a senior editor at Military Times. She's reported on veterans and military communities for nearly a decade and has also covered technology, politics, health care and crime. Her work has earned multiple honors from the National Coalition for Homeless Veterans, the Arkansas Associated Press Managing Editors and others.

Allison Erickson is a journalist and U.S. Army Veteran. She covered military and veterans' affairs as the 2022 Military Veterans in Journalism fellow with The Texas Tribune and continues to cover the military community. She has written and reported on topics such as migration, politics, and health.