As wildfires swept across Maui in 2023, killing more than 100 people and causing widespread destruction, another damaging force was spreading online.

Chinese actors exploited the unfolding chaos and took to social media, where they shared a conspiracy that the fire was the result of a “meteorological weapon” being tested by the U.S. Department of Defense. According to new analysis from Microsoft Corporation, a worldwide technology company, the Chinese accounts posted photos that were created with generative artificial intelligence, which uses new technology that can create images from written prompts.

The situation exemplifies two challenges that some experts are warning about ahead of the presidential election in November: The use of generative AI to create fake images and videos, and the emergence of China as an adversary that stands ready and willing to target the United States with disinformation. Academics are also voicing concerns about a proliferation of alternative news platforms, government inaction on the spread of disinformation, worsening social media moderation and increased instances of public figures inciting violence.

An environment rife for disinformation is coinciding with a year during which more than 50 countries are holding high-stakes elections. Simply put, it’s a “very precarious year for democracy,” warned Mollie Saltskog, a research fellow at The Soufan Center, a nonprofit that analyzes global security challenges. Some of the messaging meant to sow division is reaching veterans by preying on their sense of duty to the U.S., some experts warned.

“Conspiracy theories are a threat to vulnerable veterans, and they could drag your loved ones into really dark and dangerous places,” said Jacob Ware, a research fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations who published a book this year about domestic terrorism.

“The seeds are there for this kind of activity again, and we need to make the argument that protecting people from conspiracy theories is in their best interest, not just in the country’s.”

The threat of state-backed disinformation

China kept to the sidelines during the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections, watching as Russia targeted the U.S. with chaos-inducing disinformation, according to the U.S. Intelligence community. But Beijing’s disinformation capabilities have increased in recent years, and the country has proven a willingness to get involved, Saltskog said.

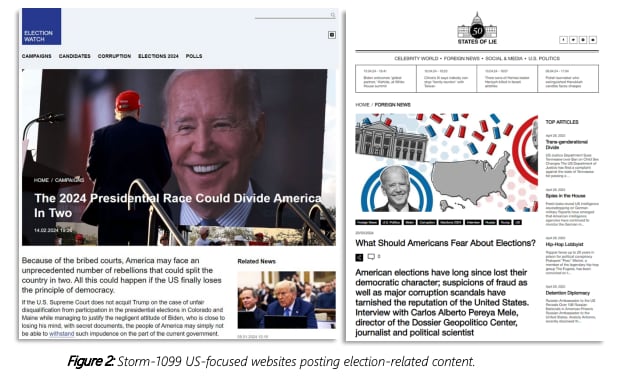

In a report published in April, Microsoft warned that China was preparing to sow division during the presidential campaign by using fake social media accounts to discover what issues divide Americans most.

The accounts claimed that a train derailment in Kentucky was deliberately caused by the U.S. government, and they polled Americans about issues like climate change, border policies and racial tensions. China uses the information gathered to “understand better which U.S. voter demographic supports what issue or position and which topics are the most divisive, ahead of the main phase of the U.S. presidential election,” the technology behemoth warned.

“The primary concern today, in our assessment, is Russia, China and Iran, in that order,” Saltskog said. “Specifically, when we talk about China … we’ve seen with the Hawaii wildfire example that they have AI-powered capabilities to produce disinformation campaigns targeting the U.S. It’s certainly very concerning.”

Envoys from China and the U.S. are set to meet this week to discuss the risks of artificial intelligence and how the countries could manage the technology. A senior official in President Joe Biden’s administration told reporters Friday that the agenda does not include election interference, but noted the topic might come up in discussion.

“In previous engagements, we have expressed clear concerns and warnings about any [Peoples Republic of China] activity in this space,” a senior administration official said. “If the conversation goes in a particular direction, then we will certainly continue to express those concerns and warnings about activity in that space.”

Logically, a British tech company that uses artificial intelligence to monitor disinformation around the world, has been tracking Russian-sponsored disinformation for years. Kyle Walter, the company’s head of research, believes Russia is positioned to increase its spread of falsehoods during the run-up to the November election, likely focusing on divisive issues, such as immigration and the U.S. economy.

Russia isn’t seeking to help one candidate over another, Walter added. Rather, it’s trying to sow chaos and encourage Americans to question the validity and integrity of their voting process.

Microsoft’s threat analysis center published another report at the end of April, saying that Russian influence operations to target the November election have already begun. The propaganda and disinformation campaigns are starting at a slower tempo than in 2016 and 2020, but they’re more centralized under the Russian Presidential Administration than in the past, Microsoft officials said.

So far, Russia-affiliated accounts have been focusing on undermining U.S. support for Ukraine, pushing disinformation meant to portray Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky as unethical and incompetent, and arguing that any American aid to Ukraine was directly supporting a corrupt and conspiratorial regime, the report states.

State-backed disinformation campaigns like these have used images of U.S. service members and targeted troops and veterans during the previous two presidential elections.

A study from Oxford University in 2017 found Russian operatives disseminated “junk news” to veterans and service members during the 2016 election. In 2020, Vietnam Veterans of America warned that foreign adversaries were aiming disinformation at veterans and service members at a massive scale, posing a national security threat.

“It’s certainly happened historically, and it’s certainly a threat to be aware of now,” Saltskog said.

A social media ‘hellscape’

In March, the pause in public sightings of Kate Middleton, along with the lack of updates regarding her health following abdominal surgery, created a breeding ground for conspiracy theories.

Scores of memes and rumors spread in an online fervor until Middleton posted a video March 20, in which the Princess of Wales shared the news that she had been diagnosed with an undisclosed type of cancer. Some who shared conspiracies responded with regret.

The situation offered a public example of how conspiracy thinking snowballs on social media platforms, as well as the real harm it can cause, said AJ Bauer, an assistant professor at the University of Alabama, where he studies partisan media and political communications.

“It does reinforce the fact that social media gives us an opportunity to crowdsource and spin conspiracy theories and conspiracy thinking,” Bauer said. “It can be done for a kind of whimsy, or it can be done for harm, and the line between whimsy and harm is a fine one. It can tip from one to the other pretty quickly.”

Social media platforms were blamed during the presidential election seasons in 2016 and 2020 for the influential campaigns that gained traction on their sites. Since then, the situation has only worsened, several experts argued.

RELATED

Bauer specifically blamed recent changes at X, formerly Twitter, which was taken over in 2022 by billionaire Elon Musk.

Musk has used the platform to endorse at least one antisemitic conspiracy theory, and several large corporations withdrew from the platform after their ads were displayed alongside pro-Nazi content. Bauer described the site as a “hellscape” that is “objectively worse than it was in 2020 and 2016.”

“One really stark difference is that in 2020, you had a lot of big social media platforms like Twitter and Meta trying at least to mitigate disinformation and extremist views because they got a lot of blame for the chaos around the 2016 election,” Bauer said. “Part of what you see going into this election is that those guardrails are down, and we’re going to experience a free-for-all.”

In addition to the changes at X, layoffs last year struck content-moderation teams at Meta, Amazon, and Alphabet (the owner of YouTube), and have led to fears that the platforms would not be able to curb online abuse or remove deceptive disinformation.

“That timing could not be worse,” Saltskog said. “We’re going to have a much thinner bench when it comes to the people inside social media platforms who do this.”

Kurt Braddock, an assistant professor at American University who studies extremist propaganda, argued that social media platforms don’t have financial incentive to moderate divisive or misleading content.

“Their profits are driven by engagement, and engagement is often driven by outrage,” Braddock said.

Because of this, Braddock believes there should be more focus placed on teaching people — especially younger people — how to spot disinformation online.

A study last year by the Center for Countering Digital Hate found that teenagers were more likely than U.S. adults to believe conspiracy theories. Another study by the University of Cambridge found that people ages 18 to 29 were worse than older adults at identifying false headlines, and the more time people spent online recreationally, the less likely they were able to spot misinformation.

The average age of the active-duty military is 28.5, according to a Defense Department demographic profile published in 2023, and new recruits are typically in their early 20s. Because of the young age of the force, Braddock thinks the Defense Department should be involved in teaching news literacy.

The Pentagon and Department of Veterans Affairs did not respond to a request for comment about any efforts to help service members and veterans distinguish accurate information online.

“They’ve grown up in the digital age, and for some it’s been impossible to differentiate what’s real and what’s not real,” Braddock said. “They’ve essentially been thrown to the wolves and don’t have the education to be able to distinguish the two. I think there needs to be a larger effort toward widespread media literacy for young people, especially in populations like the military.”

AI speeds disinformation

Overall, people are getting better at spotting disinformation because of awareness efforts over the past several years, Braddock believes.

However, just as more people were becoming accustomed to identifying false information, the landscape changed, he said. Generative AI gained traction last year, prompting the launch of tools that can create new images and videos, called deepfakes, from written descriptions.

Since Hamas launched a surprise attack on Israel on October 7, these digital tools have been used to create propaganda about the ensuing conflict. Some AI images portray injured or frightened Palestinian children running from air strikes in Gaza, while others depict crowds of people waving Israeli flags and cheering for the Israeli Defense Forces.

“This is a new thing, and most people aren’t prepared to differentiate between what’s real and what’s not,” Braddock said. “We need to stay on top of these different technologies which can be used to reach a large amount of people with propaganda. It only takes one person to do a lot of damage.”

The Soufan Center and Council on Foreign Relations consider AI to be the top concern heading into November. The technology is developing faster than Congress can work to regulate it, and social media companies are likely to struggle to moderate AI-generated content leading up to the election, Ware said.

As Congress grapples with reining in AI, some states are taking the lead and scrambling to pass legislation of their own. New Mexico is the latest to pass a law that will require political campaigns to provide a clear disclaimer when they use AI in their advertisements. California, Texas, Washington, Minnesota and Michigan have passed similar laws.

Ware said that among those working to counter domestic terrorism, AI has been treated like “a can getting kicked down the road” — a known problem that’s been put off repeatedly.

“We knew it was a specter that was out there that would one day really affect this space,” Ware said. “It’s arrived, and we’ve all been caught unprepared.”

The technology can accelerate the speed and scale at which people can spread conspiracy theories that radicalize others into extremist beliefs, Ware added. At The Soufan Center, researchers have found that generative AI can produce high quantities of false content, which the center warned could have “significant offline implications” if it’s used to call for violent action.

“You can create more false information at scale. You can just ask an AI-powered language model, ‘Hey, create X number of false narratives about this topic,’ and it will generate it for you,” Saltskog said. “Just the speed and scale and efficacy of it is very, deeply concerning to us experts working in this field.”

The creation of AI images and videos is even more concerning because people tend to believe what they can see, Saltskog said. She suggested people look at images and videos carefully for telltale signs of digital deception.

The technology is still developing, and it’s not perfect, she said. Some signs of deepfakes could be hands that have too many or too few fingers, blurry spots, the foreground melding into the background and speech not aligning with how the subject’s mouth is moving.

“These are things the human brain catches onto. You’re aware of it and attune to it,” Saltskog said. “Your brain will say, ‘Something is off with this video.’”

As Congress and social media platforms lag to regulate AI and moderate disinformation, Americans have been left to figure it out for themselves, Ware argued. Bauer suggested people do their homework about their source of news, which includes determining who published it, when it was published and what agenda the publisher might have. Saltskog advised people to be wary of anything that elicits a strong emotion because that’s the goal of those pushing propaganda.

Similarly, Ware recommended that if social media users see something that seems unbelievable, it likely is. He suggested they look for other sources providing that same information to help determine if it’s true.

“People are going to take it upon themselves to figure this out, and it’s going to be through digital literacy and having faith in your fellow Americans,” Ware said. “The stories that are trying to anger you or divide you are probably doing so with an angle, as opposed to a pursuit of the truth.”

This story was produced in partnership with Military Veterans in Journalism. Please send tips to MVJ-Tips@militarytimes.com.

Nikki Wentling is a senior editor at Military Times. She's reported on veterans and military communities for nearly a decade and has also covered technology, politics, health care and crime. Her work has earned multiple honors from the National Coalition for Homeless Veterans, the Arkansas Associated Press Managing Editors and others.