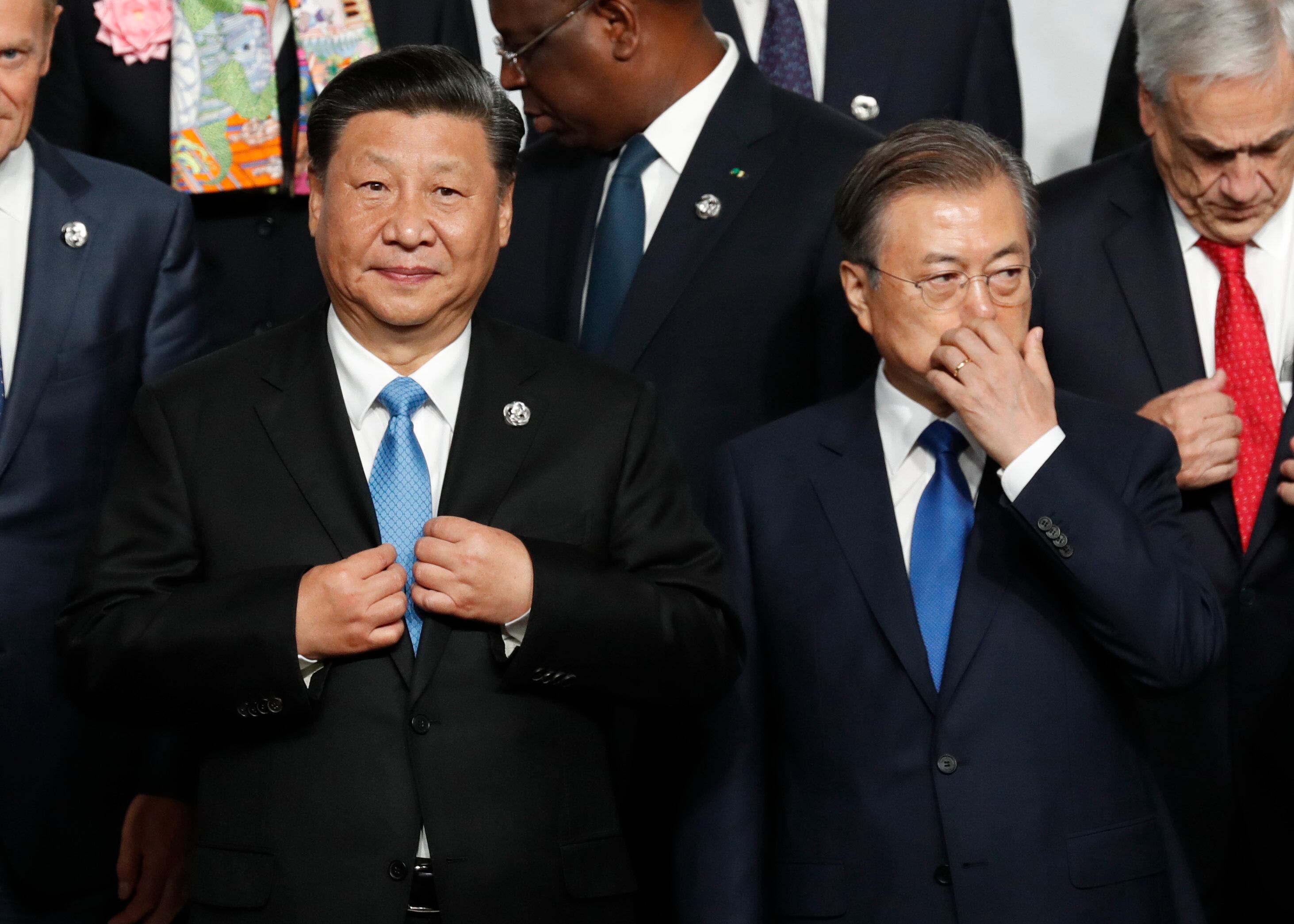

WASHINGTON — The tweet came Aug. 2, following an emergency meeting of the South Korean government. It was a photo of President Moon Jae-in, sent out from the government’s official Twitter feed, with text plastered over it and a succinct message:

“We will never again lose to Japan.”

In what the U.S. has declared to be an era of great power competition, part of the plan to blunt Chinese influence in the region comes from relying on Japan and South Korea, two key American partners, to focus on shared threats in the region. But since October, new rifts have formed in the Japan-South Korea relationship, with the two countries in the last few weeks trading major economic blows and neither side dialing down the rhetoric.

Now, there are concerns that what have been social and economic tensions could boil over and destroy a key intelligence sharing arrangement, one the U.S. had hoped to use as a platform for building greater defense cooperation between the two neighbors. Should that happen, it may impact America’s long-term strategy in the region.

“This isn’t Japan and Korea going to war,” said Patrick Cronin, a regional expert with the Hudson Institute. “But it is a worse situation than we should be allowing right now, and it’s dangerous if it spills over into things like severing the intelligence sharing arrangement. It’s dangerous for all three countries."

“You have literally the foundation of America’s Indo-Pacific strategy being called into question at a time when it’s vital for the United States to be showing this strategy” can work, Cronin added. “We’ve had ups and down. But I don’t want to sugarcoat the fact that this deterioration of the relationship we’ve witnessed since October 2018 is fundamentally against U.S. national interests.”

Economic tensions hit military

The latest round of problems between the two countries started in October, when a South Korean court ruled that Japanese company Nippon Steel could be held liable for the use of slave labor when Japan occupied South Korea before and during World War II.

Japan has argued that the 1965 agreement that reopened relations between Seoul and Tokyo covered any questions of reparations.

Since that ruling, a series of small military incidents have inflamed the historic bilateral tensions, with cultural tensions boiling over into economic disputes in July when Japan blocked the transfer of key materials used in semiconductors and flat screens — major exports for South Korea — claiming Seoul was not preventing those key technologies from ending up in North Korea.

Then on Aug. 1, Japan removed Seoul from its “white list,” the first time a country has been removed from Tokyo’s list of trade partners with minimum export regulations. Two weeks later, South Korea returned fire by announcing it would remove Japan from its own white list.

The damage caused by this mini trade war could prove dangerous for the global economy, but national security experts are also nervously eyeing a statement from South Korean officials that it might next tear up a key intelligence sharing agreement known as the General Security of Military Information Agreement, or GSOMIA.

Signed in 2016 following years of diplomatic efforts by the United States, GSOMIA is an agreement between Tokyo and Seoul to share information about North Korea. Under the deal, Japan provides satellite imagery and electronic information among other intel to South Korea, which in turn provides human intelligence to Japan for analysis.

The deal is automatically extended each year, but either side can exit the agreement if notification is provided to the other 90 days in advance of that automatic extension. That 90-day deadline for this year falls on Aug. 24.

Experts such as Chun In-beom, a retired lieutenant general of the South Korean Army, worry that walking away from GSOMIA could result in Seoul losing access to key North Korean information.

“If GSOMIA is not extended, cooperation [with Japan] will be harder and really does not achieve any tangible benefits to South Korea,” said Chun, a former special warfare commander who had overseen combined training exercises with U.S. forces in Korea. “Information sharing will become harder and might even become worse. There is no benefit, period.”

Added Cronin: “By walking away from GSOMIA, you’re weakening deterrence and early warning, and that becomes more dangerous. It’s in nobody’s interest."

“If you throw that on the fire for political reasons, you are burning really three decades of hard-won progress in this strategic partnership that we thought we were growing,” he said.

While GSOMIA itself is fairly limited, it’s worth considering that the U.S. invested significant diplomatic effort to get the agreement signed specifically to serve as a building block to future agreements, explained Eric Sayers, a former special assistant to the head of U.S. Pacific Command, now with the Center for a New American Security.

“The medium- or long-term desire was to use this as events allowed for, the politics allowed for, to build to something bigger. You could dream on it growing to include missile defense issues because that’s not an offensive capability and is something both countries are interested in. Maybe anti-submarine operations as well,” Sayers said of the agreement.

“Getting back to the place we thought we were at after GSOMIA will be a few years away at least,” he added. “It’s like alliance ‘Chutes and Ladders,’ and we’ve just hit the big chute and gone all the way back to the beginning.”

Those looking for positive signs have pointed out that since the threat of cutting of GSOMIA was first floated this summer, South Korean officials have somewhat massaged it down, and there is a sense that military leaders there see value in the agreement. But tensions may further bleed into the military realm thanks to Dokdo, the easternmost islets of South Korea, which Japan has historically claimed as its own territory.

South Korea annually holds two rounds of combined maritime training exercises near Dokdo, but this year’s first round was delayed because of the impact it may have on the diplomatic relations between the neighboring countries. Should Seoul see Tokyo as escalating the current situation, the drills could be reactivated with little delay, according to a source at Seoul’s Ministry of National Defense.

The combined drills involve the forces of the Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps, as well as Coast Guard members. The exercises usually mobilize a 3,200-ton destroyer and a 6,500-ton Coast Guard patrol vessel, along with F-15K fighters, P-3C maritime surveillance planes and UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters.

Domestic disputes and the China factor

From a broad U.S. military perspective, the current fight between the two nations shouldn’t have a major impact on the National Defense Strategy, or NDS, said Sayers.

“Korea is very much about the [Korean] Peninsula, and to the extent the NDS means keeping the focus on great power competition, the Korean alliance and trilateral relations are about ensuring North Korea remains a cold crisis," he said. “I think the U.S.-Japan alliance is in a strong position despite some of the concerns with the potential for a rift over economic issues. And I think that alliance is the more pivotal one to the success of the National Defense Strategy in Asia.”

And some analysts are convinced China would attempt to take advantage of the situation, most likely by trying to woo Seoul — which is already more willing to engage with Beijing than Japan — through economic means.

Cronin, of the Hudson Institute, pointed to a situation from several years ago when South Korea allowed the deployment of American Terminal High Altitude Area Defense systems onto its territory.

China, claiming THAAD radars could be used to spy on its mainland, turned to economic reprisals, including cutting off tourists to South Korea, barring K-pop groups from visiting China and reducing imports of Korean made goods.

China “weaponizes everything from bananas to tourists, and it will absolutely use trade as an investment to try and sway South Korea closer to cooperation with China,” Cronin said. “South Korea being even 10 degrees less aligned with Japan gives them a path.”

He said one warning sign would be a offer from China to replace materials withheld by Japan.

This would be a problem for the increasingly China-focused Pentagon. It is no surprise U.S. Defense Secretary Mark Esper reportedly urged Japanese and South Korean leaders to maintain the agreement, during a recent visit to the region.

But experts are skeptical either side is willing to step back from the series of escalations. And that’s partly because of domestic politics.

Moon’s approval rating has increased notably in recent months as nationalistic fervor against Japan has grown. Sung-Yoon Lee, a professor of Korean studies at the Tufts University Fletcher School, said to expect Moon to “ride the crest of the waves of anti-Japanese sentiment as long as possible with the view toward winning the general election in April 2020."

“Unless [Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo] Abe backs down and expresses regret, Moon will not be the one to flinch — no matter how damaging such a standoff is to [South Korea’s] national security and economy,” Lee said. “His core support base is anti-Japan, and anti-Japanese politics always sells. U.S. mediation or exhortations will be received politely, then put away in storage.”

Abe, too, benefits domestically by not backing down to South Korean demands, with a history of visiting controversial nationalist shrines and a stated desire to push Japan into more of a global role militarily. The move to block the materials for Korean parts came as Japan was gearing up for a national election that saw Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party take a majority.

This is hardly the first time the two nations have entered into a spat, but traditionally the United States has stepped in and deescalate the situation. Analysts are skeptical that will happen this time, given President Donald Trump’s flavor of diplomacy, and because he is currently applying public pressure on Seoul to pay more for its own defense.

“The U.S. administration deserves some responsibility, however, for the spiraling downturn,” said Victor Cha, a former director for Asian affairs at the National Security Council, now with the Center for Strategic and International Security. “There was a time when the deputy secretary of state would hold quarterly trilaterals that was as important for signaling as it was for strategy. None of that exists today.”

Those looking for signs of optimism can point to Moon’s Aug. 15 keynote address to the nation, in which he said: “If Japan chooses the path of dialogue and cooperation, we will gladly join hands. We will strive with Japan to create an East Asia that engages in fair trade and cooperation.”

However, in the same speech, Moon hit Japan for its “unwarranted export restrictions," and he closed the speech with a pledge that economic development is “the road to overtaking Japan and guiding it toward a cooperative order in East Asia."

Ultimately, any wedge between two major U.S. allies in the region benefits the players who would like to see limits on American influence in the Pacific, said Cronin.

“Beijing, Moscow, Pyongyang — whatever else they are doing, one thing they are trying to do for sure is find seams in U.S. alliances in the region. Their power grows without doing anything as long as the power of the three democracies is not harnessed,” he said. “This situation seems very much in both their political and military interests.”

Jeff Jeong in Seoul contributed to this report.

Aaron Mehta was deputy editor and senior Pentagon correspondent for Defense News, covering policy, strategy and acquisition at the highest levels of the Defense Department and its international partners.