Editor’s note: This piece was first published in The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization dedicated to educating the public on military service. Subscribe to their newsletter.

During the first week of December 1991, my wife, Lin, and I met our friend Richard Fiske for dinner at the Chart House in Honolulu, Hawaii, as we had done on many occasions.

I’d been stationed at Hickam Air Force Base, Hawaii, for three years in the late 1960s. After I retired from the federal government, Lin and I moved to Oahu, where we lived aboard our sailboat in Ala Wai Harbor. By the 80s, Lin worked at what was then Banana Republic Travel & Safari, and she first met Mr. Fiske there.

He volunteered for the USS Arizona Memorial and liked the sort of clothing sold by Banana Republic. That day, he walked in wearing his tour guide vest and a World War II Arizona Survivor garrison cap, and soon, he was one of Lin’s regular customers.

During one visit, Lin told Mr. Fiske that her father planned to visit us in Hawaii—his first trip to the island since World War II. He’d sailed into Pearl Harbor on a minesweeper and later served as a sailor aboard the USS Natrona.

Mr. Fiske encouraged Lin to bring her father to the Arizona Memorial and ask for him so they could meet. Of course, we did, and the two World War II veterans hit it off wonderfully. That meeting also began our tradition of bringing friends to meet Mr. Fiske. We’d always call to let him know we were coming, and he’d meet us at the memorial. Afterward, we’d walk to the Chart House restaurant and break bread together.

Mr. Fiske was a jovial man, but he was unusually quiet over this particular dinner in December 1991.

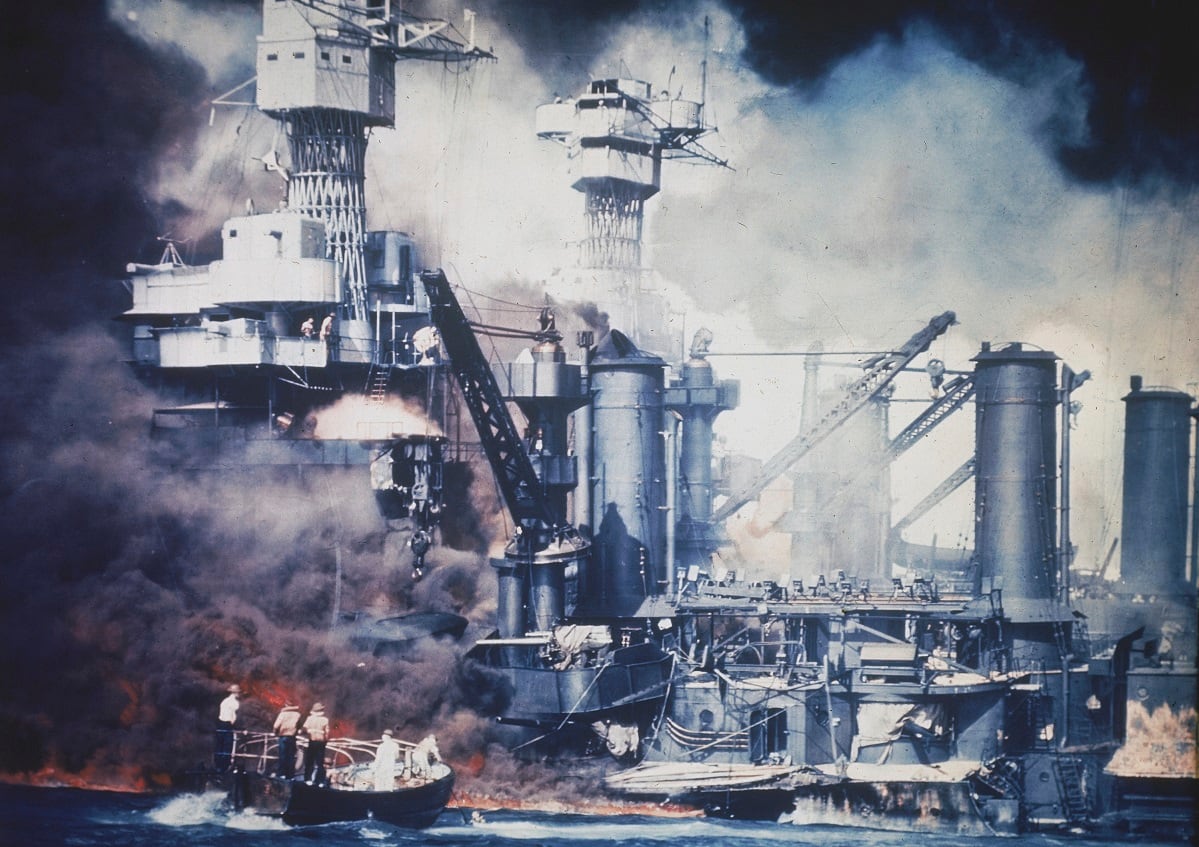

Fifty years earlier, Mr. Fiske served as a young private and bugler on the USS West Virginia. He stood on the quarterdeck on the morning of Dec. 7, 1941, when the second wave of Japanese planes flew up The Slot—the Kolekole Pass through the Waiʻanae mountains on Oahu.

Mr. Fiske recalled that as the dive-bombers wreaked havoc, he saw a plane headed straight for the West Virginia. He told us it came so close he could make out the pilot’s face. A tremendous explosion followed. Mr. Fiske took cover with the rest of the men until they received orders to abandon ship. Mr. Fiske jumped overboard into the acrid water, slick with fuel, hot with flames, and alive with the terrible cries of his injured shipmates.

That was Mr. Fiske’s introduction into World War II. Three years later, he landed on Iwo Jima, which he once described as “36 straight days of Pearl Harbor.” At the war’s end, he joined the Air Force and served in Korea and Vietnam before retiring as a master sergeant in 1969—the same year I left Hickam.

He told us that despite all he’d witnessed and experienced, the pilot’s face at Pearl Harbor still haunted him 50 years later. He’d woken up in cold sweats countless times over the decades, even as he served as a tour guide near the very place that changed him and the course of history.

“Will you be at the 50th anniversary ceremonies at Pearl Harbor?” a quiet Mr. Fiske finally asked us.

When we answered that we planned to be there, he seemed unsettled, and we asked if he was OK.

RELATED

“He’ll be there this time,” Mr. Fiske answered.

“Who will be there?” I asked.

“The pilot who sunk my ship. I have hated that SOB for 50 years, and now I’ll finally see him again, but not through my gun sights.”

Mr. Fiske was visibly upset now and hardly ate any of his supper. At the end of the meal, Lin hugged him goodnight. We watched worriedly as he walked off toward his apartment.

As promised, Lin and I arrived at Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1991. Through the tourists and members of the news media, we spotted Mr. Fiske. He stood among other Pearl Harbor survivors dressed in white garrison caps as they reminisced.

Suddenly it turned eerily silent.

I looked up and saw an older Japanese man dressed in business clothes. His name was Zenji Abe, I would later learn. Just then, Mr. Abe nodded and bowed his head in honor as he slowly walked toward the group. Mr. Fiske acknowledged him and began slowly walking toward Mr. Abe.

When they were about two feet apart, a look of peace seemed to settle over Mr. Fiske’s face and he reached for Mr. Abe. They embraced and held on to each other, tears streaming down both their faces. I began to cry. So did the other bystanders. There was no applause. Just respectful silence among the several hundred survivors and family members.

I believe that for Richard Fiske and Zenji Abe, it was official. The war was over at long last.

That evening, in the waning daylight, Mr. Fiske played taps as the sun melted into the sea—an emotional and fitting close to the day.

Both men remained friends for the rest of their lives. Mr. Abe paid to have roses sent to the Arizona Memorial every year, and Mr. Fiske would place the flowers in front of the memorial and play taps on his bugle. After Mr. Fiske’s death in 2004, Mr. Abe traveled from Japan to pay his respects.

This week marks 82 years since the attack on Pearl Harbor and 32 years since I witnessed the remarkable birth of a friendship between two men who’d once been at war. It’s hard to believe that so much time has passed and that many of these men are now gone. This is my story of the events of that day as I remember them.

Rest in peace, you gallant warriors. You now belong to the ages.

Frank A. Vargo is a veteran of the Air Force, where he served as a squadron photographer. He has also worked as a legislative aide for the Hawaii state senate and as an FBI identification specialist. He retired as a federal police officer. He lives in Montana with his wife, Lin.