WASHINGTON — “What the hell are we doing here?”

That was the question then-Col. Randy George asked then-Lt. Col. Brad Brown when he first visited Combat Outpost Keating in Afghanistan in late 2008.

Ahead of their official deployment to Afghanistan, the two were attending a memorial service for the most recent commander of the base, who had been killed by a roadside bomb that exploded nearby, Brown recalled in an interview with Defense News. That commander wasn’t the first soldier to die there or the last.

Brown said it was clear to George the outpost, along with several others in the northeast region of the country, needed to close.

COP Keating, nestled in a valley and surrounded by insurgents roaming the mountains, relied almost entirely on support from helicopters because the single road leading to the post was difficult to access for anything larger than a Humvee.

The outpost had been named for 1st Lt. Ben Keating, who died when his vehicle fell off a cliff near the base, but closing the facility proved difficult.

Afghanistan in 2008, Brown said, “really became sort of a cyclical process where you just go, you do your time, you try not to get anybody killed and you leave and hand it over to the next guy.”

“For Randy, that wasn’t good enough,” Brown said.

George declined requests for an interview ahead of the Senate confirmation process.

“The guy that may have established that base ... as a battalion commander is now a division commander,” Brown said. “When you say, ‘Well, this is a stupid place to put a base,’ you’re effectively telling the person who did that, that was dumb, it was a mistake and everybody that fought there and died there wasted their time.”

George still wanted to move forward and eventually received approval, but in fall 2009, before it could be closed, the vulnerable outpost was nearly overrun by Taliban fighters. The attackers killed eight U.S. soldiers and four Afghan army soldiers defending the outpost.

In a 2017 Army video, George recounted how the troops “were in a very difficult position in very difficult terrain at the bottom of a mountain, basically the bottom of a hole and were attacked by more than 300 Taliban.”

After an investigation into the attack, Brown and a captain received formal reprimands, while George and a second captain received admonishments — a similar but less severe form of administrative punishment. George continued to seek to close COP Keating and other remote outposts, shuttering them by the end of his year-long deployment.

“He did everything to ensure that the people that were there got every bit of support that they could get,” Brown said. “I always felt that he was in our corner.”

Now George, the vice chief of staff of the U.S. Army, is nominated to become the service’s top uniformed officer and the principal military adviser to Army Secretary Christine Wormuth. Former colleagues say he will benefit from his experience working to advocate for troops, like he did for those who defended COP Keating, as recruitment and retention are expected to take center stage.

At the same time he’ll have to manage the pressure on force structure, he is also set to face tightened budgets and a push to get dozens of key modernization programs to troops.

“He’s getting squeezed on all fronts,” said Tom Spoehr, a retired Army three-star general who is now with the Heritage Foundation. “He’s getting squeezed on manpower, is being squeezed on money and ... for the foreseeable future, there’s going to be trade-offs that need to be made.”

George is set to appear Wednesday at a confirmation hearing before the Senate Armed Services Committee.

In your corner

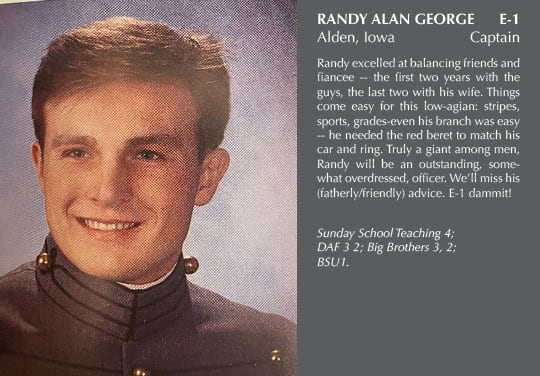

George, who was born in Iowa, graduated from West Point in 1988. He began his career as an infantry officer and served in Desert Storm as a lieutenant in the 101st Airborne Division.

He initially deployed to Iraq in 2003 as deputy commander of the 173rd Airborne Brigade based in Italy, and again in 2004 as the commander of the 1st Battalion, 187th Infantry Regiment.

According to colleagues who saw him lead, like Brown, he quickly gained a reputation as relatable and a supporter of his troops.

Retired Lt. Gen. James Pasquarette, who worked with George multiple times in his career, told Defense News George is authentic.

“That’s what makes him connect with soldiers,” he said.

At a conference in Asadabad, Afghanistan, in late 2009, George sought common ground with the audience of Afghan leaders.

“I came from a very small, small village town like many of you find right here,” he told them, according to an Army video. “My father was a farmer, he didn’t have a lot of land. We weren’t a very wealthy family and we relied on the government to help us contribute to society. We relied on the government to help protect us and provide the right environment to raise a family.”

While serving as a brigade commander in Afghanistan, George outfitted his entire brigade with lighter equipment, Brown said, including armor, knee pads and sleeping bags, to cope with challenging mountainous terrain.

“We were famously the first unit to go in in like non-standard boots,” Brown said.

George bought high-quality hiking boots — two pairs for every soldier in the unit — even though the shoes weren’t Army-approved, Brown said.

“It’s breaking the norms that the Army has that are so ingrained about uniformity and what’s issued,” he added.

When George was serving as I Corps commander at Joint Base Lewis McChord in Washington state during the COVID-19 pandemic, he walked the base with his wife Patty, a fellow West Point graduate, stopping people along the way to see if he could help them, Shane Pospisil, who was I Corps’ command sergeant major at the time, told Defense News.

Those conversations almost always led to action, Pospisil said; if George couldn’t solve the problem, he’d contact the person to explain why.

During this stint, George secured funding to fix the runway at the base and identified private money to open the first Defense Department Children’s Museum there, Pospisil said.

George prefers face-to-face interactions over video teleconferences or phone calls, the sergeant major noted. He often chose to walk around the base with Pospisil and other staff to discuss work rather than hash things out in the office.

His focus on respectful connection also extended to those whom he met for less-favorable reasons, according to retired Maj. Gen. Pat Donahoe. The two-star general’s retirement was delayed in 2022 due to an inspector general investigation into his social media conduct, which threatened to see his retirement pension docked.

George was the Army’s messenger about his fate, Donahoe recounted in an exclusive January interview. But rather than focusing on Donahoe’s social media policy violations, or the media controversy they caused, the once-admonished vice chief wanted to hear how the Army could improve its administrative investigation processes and modernize its approach to social media.

“He took notes through the whole 45 minutes; he was inquisitive; he wanted to understand my perspective,” Donahoe recalled, noting the “cordial and professional” interaction was their first.

Challenges ahead

Just as he did in closing Keating and other remote outposts in Afghanistan, George will face a series of strategic decisions if confirmed as Army chief of staff.

George would take command of an Army that has struggled in recent years to meet recruiting goals. As a result, it has reduced its end-strength numbers and its objectives even as Army officials want to see the force grow.

The Army’s planned end strength in fiscal 2024 is 452,000 active duty troops. In FY23, the Army planned for a force of 473,000. The service expected in its FY23 budget to increase its end strength back to 485,000 active duty soldiers within five years, but is now projecting 464,000 active duty troops in FY28.

War is raging on in Ukraine, and the Army continues to send weapons and equipment in large numbers as it works to rapidly replenish stock. The Army is expected to soon decide how much it will need to replenish munitions expended in the war in Ukraine to ensure the right balance of stock to support allies and partners while preparing for potential large-scale wars in the future.

And the Army is pushing hard to modernize, investing billions in over 35 new programs meant to help the service be able to fight near-peer adversaries across all domains. This modernization initiative follows years of failure to develop and procure new weapon systems and could face headwinds due to projected flat budgets and higher inflation.

His past suggests George will prioritize soldiers and their families, according to many of his former colleagues.

Recruiting and budget issues will likely be George’s biggest challenges and he’s already tackling these issues as vice chief of staff, Spoehr, the Heritage analyst, told Defense News.

George has shown he’s willing to make hard decisions, said Tony DeMartino, a retired Army colonel, who served with George multiple times throughout his career, including in Afghanistan. “The Army needs that, the Army doesn’t need to muddle along.”

It is not the first time Wormuth and George have worked together, which will be beneficial, Brown said. George collaborated on the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review Wormuth led as under secretary of defense for strategy, plans and forces. At the time, George was deputy director for regional operations and force management in the J-3.

If confirmed, George and Wormuth together will likely have to make tough decisions when it comes to how it meets ambitious modernization goals using newer tools like Army Futures Command to usher in not just new tech, but redesigned formations that make sense for evolving warfare against near-peer enemies.

Brown said he hopes George will “break the model [and] be innovative,” rather than accepting the “way we’ve always done it.”

Jen Judson is an award-winning journalist covering land warfare for Defense News. She has also worked for Politico and Inside Defense. She holds a Master of Science degree in journalism from Boston University and a Bachelor of Arts degree from Kenyon College.

Davis Winkie covers the Army for Military Times. He studied history at Vanderbilt and UNC-Chapel Hill, and served five years in the Army Guard. His investigations earned the Society of Professional Journalists' 2023 Sunshine Award and consecutive Military Reporters and Editors honors, among others. Davis was also a 2022 Livingston Awards finalist.