Editor’s note: Sept. 24 marks Gold Star Mother’s and Family’s Day, a holiday with roots that pre-date World War II and serves to honor those whose sons, daughters, parents and siblings have made the ultimate sacrifice.

Marine Lance Cpl. Christopher Phoenix-Jacob Levy made such a sacrifice Dec. 10, 2011, three days after suffering fatal wounds during combat operations in Afghanistan’s Helmand province. That story, told here by Levy’s Gold Star Mother, Amanda Jacobs, is one of thousands honored by family members and others not just on Sept. 24, but throughout the year:

He was 11 when 9/11 hit ... and I picked him up at school. They were shutting down schools, they were shutting down everything. At this point, only one of the towers had fallen. And by the time I’d picked him up, the second tower had fell. He was curious about what’s going on and I said, “Well, they’re thinking it’s terrorists. They don’t know.”

And he said, “I want to get the person who did that.”

And I said, “Well, they’ll get him.”

He said, “No, I’m going to get him. I want to be a Marine.”

He’d never mentioned anything about the military. And I was like, “Well, by the time you get old enough, all the threats will be over.” Of course, in my lifetime, I’d never seen any extended wars. You’d have some conflict, and no big deal. So I had no reason to believe it wouldn’t be over by the time he’d graduated high school.

Unfortunately, in 2009, when he graduated, it still wasn’t over. He did the Delayed Entry Program with the Marine Corps and left Father’s Day of 2009 for boot camp, which was probably the longest 13 weeks of my life. You know, you’re used to talking to him every day, seeing him every day, fussing at him every day, then all of a sudden, 13 weeks and I’ve got to wait for someone to tell me I can talk to my kid? I was not a happy mom.

He came home, he graduated, and I just remember at his graduation, he pulled me to the side and he said he had a gift for me. …

For 18 years, I got nothing but handmade stuff from school, or pictures, or something — kids don’t really think, “Oh, I need to invest in something for Mom and Dad for their birthday,” which is fine.

He had bought me a ring. A smaller version of his Marine Corps ring. … He said, “Mom, I’m a Marine and I only made it this far because of you.” …

He told me he got what he wanted for his MOS. And I said, “Really? Tell me what you’re going to be doing, what you’re going to be working on.” And he said, “Infantry!”

Again, not what I wanted to hear, but he was happy.

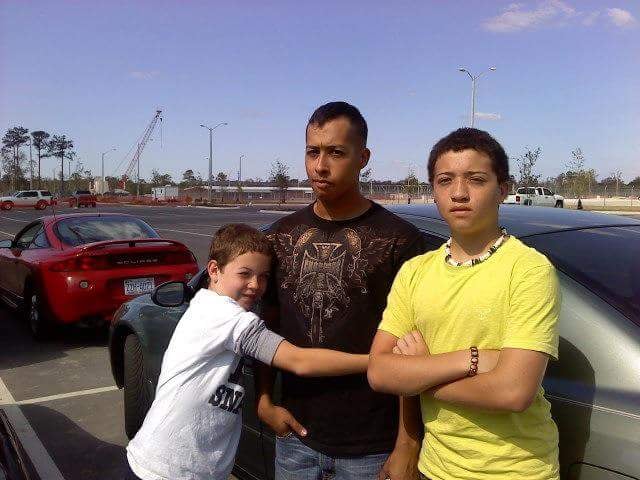

Levy would be stationed at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, only a three- or four-hour drive from his family home.

He called and said, “We’re going to Afghanistan. To combat.” I’m like, not good, not good. Outside looking in, all of us ordinary people were seeing that it’s really getting crazy over there, with bin Laden, and they’re trying to find him, they can’t find him. He said, “Don’t worry, I’ll keep you posted.”

We had a lot of conversations, nothing to really freak out about. So we’re watching the news, and of course he tells me, “Don’t watch the news. I’ll let you know if I’m OK.”

And I remember like it was yesterday, watching the news saying bin Laden’s dead. … About 30 minutes later, I get a phone call: “Momma, I’m coming home.” And I say, “You’re coming home! Do you know bin Laden’s dead?” And he’s like, “I’m here. I know.”

He actually came home Mother’s Day 2011. It was a great Mother’s Day. Between that time and his 21st birthday, I couldn’t ask for anything else. … My little boy was no longer a little boy.

The Marine soon decided his work wasn’t done in Afghanistan. He wanted to go back before his unit was scheduled to return.

I said, “Isn’t your group scheduled to go back in February?” And he said, “Yes, but I need to get back over there. Some of my buddies are over there and I want to finish what I started.” And I said, “Well, just wait.” And he said, “Well, it’s a little late — I’ve already volunteered to go back with another group.”

I was like, “Really?” He said, “Yes.”

He was going back as what they call [a] “combat replacement.” And I said, “You understand what that means? You are replacing men who were in combat, who didn’t make it or will never go back.” And he said, “I know, but I’ll be fine. I made it through the first one. …”

He left on October the 7th. I got emails, phone calls, off-and-on stuff. The last phone call was November the 14th. I was hoping he was calling to say, “Hey, I’m gonna be home for Thanksgiving,” because he had not been home for Thanksgiving or Christmas the past couple of years.” And he was like, “No, but I need to tell you, we’re going into a hot spot, and I won’t be able to talk. It’s for a couple of weeks, no phone calls, no emails, but everything will be fine.” ...

Jacobs worked at a courthouse. It was early December, less than a month since she had heard from her son.

I was at work. And at 12:32, I got — you get a coded message on your phone. And then after that came a message, you’ll get a phone call. There’s something serious.

I got the call, and they asked where I was at … they said, “We need you to come home.” And at this point, I was like, “No, you need to tell me what’s going on.” And they said, it’s in regards to Lance Cpl. Levy, let us know how long it’s going to be until [you get home] and we’ll meet you there.”

Forty-five minutes seemed to turn into three hours, driving home. And I came down my road, and I could see the car. They followed me in, and we got into the house. And not the recruiter or individuals I was used to seeing. This person was a little more decorated than usual.

They had regretted to inform me that my son had sustained a gunshot wound to the head and was in surgery. And so, at that point, I was like, “He’s alive?” And they tell me, “Yes ma’am, he’s alive, they’re working as hard as they can.”

Well, what do I need to do? They told me to pack my clothes, I was going to Germany for 30 days. ... They gave me a number to call every hour on the hour if I wanted to, which I did, finally getting a confirmation that he was out of surgery, and was stable. I was getting ready to get onto the plane to head to Landstuhl. …

RELATED

When I got off the plane … the chaplain met me. And he wanted to know what the last information that I had was. I said, “Well, they were going to run some tests, he was having some issues, but they were going to run some tests, and they’d keep me posted.”

The chaplain told me that at this point, it was only the machines keeping him alive.

Through a hospital with “individuals torn to pieces,” Jacobs made her way to her son’s bedside.

He’s got a bandage around his head. I pull the covers back, counting fingers and toes. There was no other scars. No bruising, no shrapnel, nothing. They were explaining to me that he had no voluntary brain activity. It had ceased, and they had put him on life support.

The doctor comes in, and he says, “Ma’am, I just need to tell you your son never should’ve made it this far.” I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “Your son had a DNR. They should’ve never operated on him in Kandahar. … But by the time we realized it, we knew you were en route. ... I couldn’t not do anything, my conscience wouldn’t let me stop.”

I said, “I appreciate that.”

RELATED

And then he said, “I wanted to let you know that your son’s an organ donor.” I didn’t even know that. … And he said, “It’s still your decision, if you choose not to, but if you’re going to go with his decision of being an organ donor, this is the window we have of using the organs for anything.”

At this point, I didn’t feel any duress, or pressure, or anything … I thought about how things had fallen into place. I got to say my goodbye ... and he’d made the decision so I won’t have to worry about it. I agreed to go ahead with the organ donation.

I tell people often, I’d only give my life for two sets of people, my children and my parents. And for my son to sign on the dotted line, willing to do that, just to give his life for people he didn’t know, and then he took the next step to give his body. So there are seven people living a better life today.

Her son’s final gift to others isn’t the only gift that lives on.

On December 7 [2011], I had just put my Christmas tree up with just the lights on it … the trees hadn’t been decorated. I had presents under there. Presents I had bought for Jacob, and nothing else. Fortunately, some of the [Marines] called to check on me. They said, “How’s it going?” And I said, “Well, the other ones [Jacob’s brothers] won’t have anything for Christmas, because I’m not going out.”

Well, these guys went out and bought all kinds of boys’ stuff — video games, all that — and wrapped them, stuck them under the tree, decorated the tree before Christmas.

So that’s our little tradition: They come in, they put the trees up, they bring ornaments that remind them of Jacob, or we make ornaments here, so now we’re up to three Christmas trees. … They’re coming in and bringing their wives and their families, and it’s getting bigger and bigger. They enjoy it because they’ve gone from seeing each other every day, to now, they know they’ll at least see everybody in December.