This year marks the 70th anniversary of the integration of the U.S. armed forces. But by the time President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9981 declaring “that there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion, or national origin,” Frederic Davison had been to war for his nation and back again.

Commissioned as an Army Reserve lieutenant in 1939, Davison was called to active duty in the spring of 1941 and served in the 92nd Division (Colored) as a platoon leader, company commander, and then battalion S3 (operations/training) officer in the 366th and 371st regiments.

These units deployed to North Africa and saw combat in Italy during World War II. Known as the “Buffalo Soldier Division,” the 92nd was part of a segregated Army where black soldiers were assigned to formations under the command of white officers. While several accounts disparage the performance of African-American units in World War II, Davison commented that “we [the 366th Regiment] had two enemies to fight. We had to fight the Germans in the Apennines, and we had to fight the 92nd Division hierarchy.”

In his judgment, “It almost seemed as though there was a design for failure” as units of the division were ill-trained and under poor senior leadership.

Upon his unit’s deactivation and return to the U.S. after the war, Davison briefly rejoined his alma mater Howard University as a medical school student before accepting a regular Army commission.

Davison continued to serve, training an ROTC unit in South Carolina from 1947 to 1950. But like many returning servicemen, he was fully cognizant that the rights his soldiers fought and died to bring to those in Europe were not part of a social contract for African-American citizens on their home soil.

Within the issuance of Truman’s order in July 1948, perhaps Davison felt his faith and commitment to service would be justified. His subsequent assignments to military bases in the U.S., Germany and South Korea over the following decades of service would test this faith — his commitment never wavered.

While the Army resisted integration using arguments about morale, unit cohesion, and readiness, Davison flourished as a military leader and officer.

More: Black Military History Month

Recognized for his performance and potential, he attended professional military education programs like the infantry officers advanced course.

He was selected to be a student of the Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and ultimately selected to attend the Army War College. Then-Lt. Col. Davison joined New York Army National Guard Lt. Col. Otho van Exel as the first African-American officers to graduate from that prestigious program in 1963.

As senior military officers, Davison and van Exel witnessed a fundamental shift in a turbulent American society. The August 1963 March on Washington served as a precursor to the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Following his war college graduation assignment to the Pentagon and command of a training brigade in Texas, Davison served in combat during the Vietnam War. He was selected to be the deputy brigade commander and then commander of the 199th Infantry Brigade during the Tet Offensive of 1968.

Twenty years after Truman’s executive order, Davison was promoted to the rank of brigadier general, becoming only the third African-American to attain that rank in the U.S military.

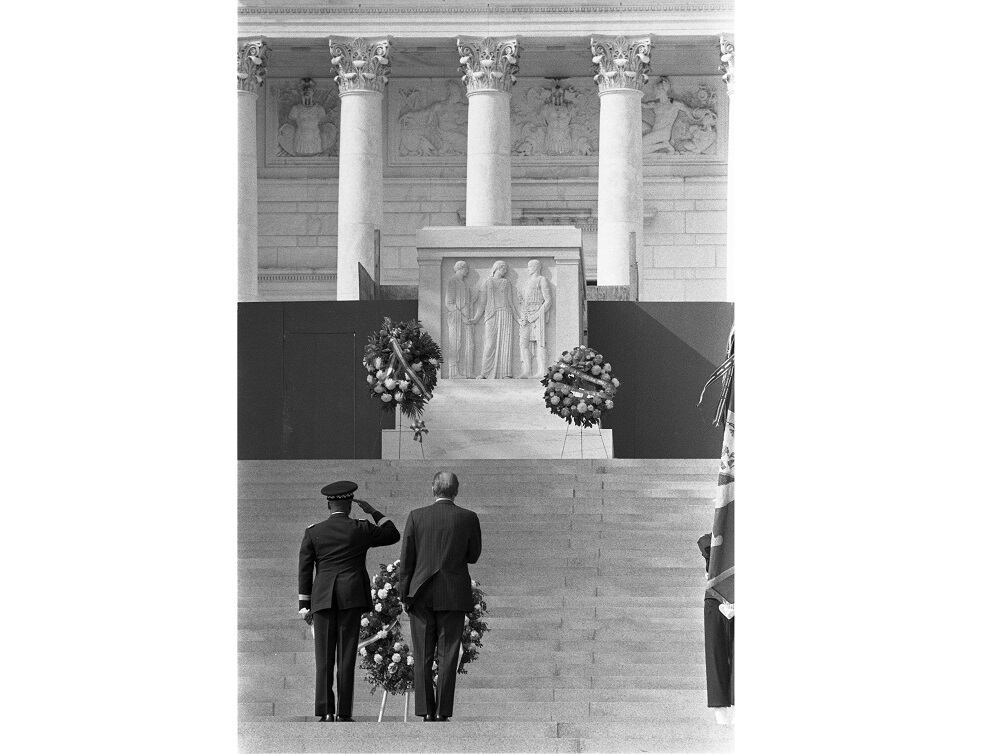

He later commanded the 8th Infantry Division in Germany before his final active- duty assignment as head of Military District Washington. It capped a career full of firsts: First African-American two-star general, first African-American to command a brigade in combat, and first African-American division commander, among others.

RELATED

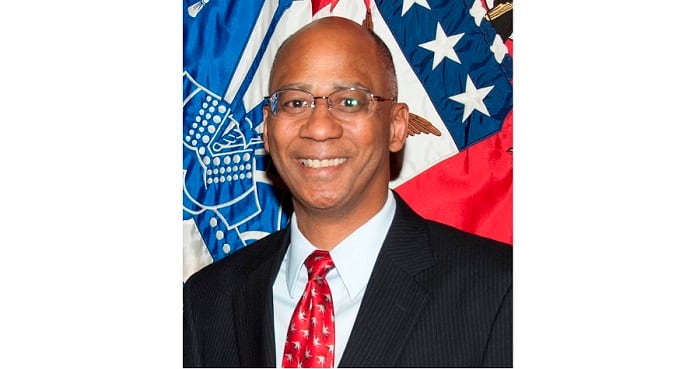

His legacy continues today in his hometown, with the current acting commanding general for District of Columbia, Army National Guard Brig. Gen. William Walker. He also helped pave the way for Lloyd Austin — an Army four-star general who was the first African-American to lead U.S. Central Command — and Gen. Vincent Brooks, now in his second four-star assignment as head of U.S. Forces-Korea.

The history of America necessarily includes the history of African-American citizens, whether civilian or military. Executive Order 9981 was immediately preceded by EO 9980, in which Truman ordered that “[a]ll personnel actions taken by Federal appointing officers shall be based solely on merit and fitness; and such officers are authorized and directed to take appropriate steps to insure that in all such actions there shall be no discrimination because of race, color, religion, or national origin.”

Progress will be demonstrated by whether people like Frederic Davison are judged by their “merit and fitness” and able to leave a legacy that makes us proud to be Americans.

Retired Army Col. Charles D. Allen is a professor of leadership and cultural studies at the Army War College.