In November 1863, Sergeant William Walker of the 3rd South Carolina Infantry took dramatic action to express a grievance shared by thousands of African American troops in the Union Army.

The 23-year-old former slave “did unlawfully take command” of Company A and march the troops to his commanding officer’s tent. There, as court-martial specifications later documented, he “ordered them to stack arms,” and when asked what this meant, replied, “We will not do duty any longer for seven dollars per month.” Walker refused an order to return to duty and told his company “to let their arms alone and go to their quarters.” They did, and “thereby excited and joined in a general mutiny.”

The young sergeant would pay for his defiance with his life. Despite a plea that he and his comrades had “only contemplated a peaceful demand for the rights and benefits that had been guaranteed them,” a military tribunal found Walker guilty of mutiny. He would be executed by firing squad on February 29, 1864.

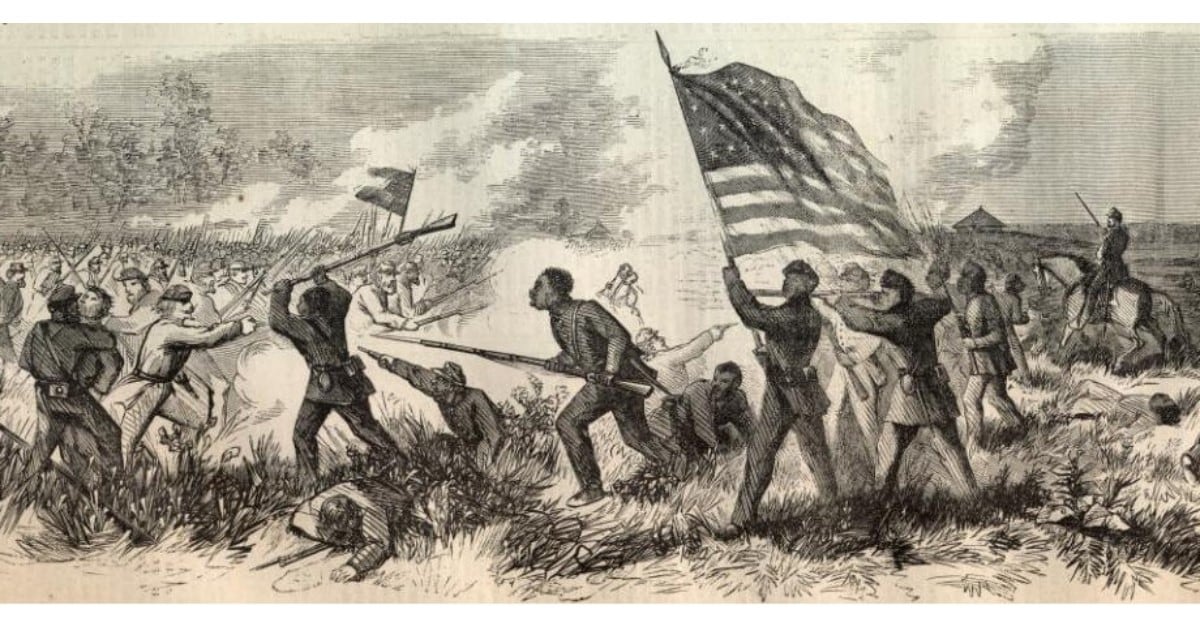

Sergeant Walker’s case illustrates the depth of resentment felt by black troops who had enlisted to fight for the Union cause and their freedom, only to find that they were to be paid less than their white counterparts. Already confronted with a combat environment in which, if captured, they might well find themselves returned to slavery or summarily shot, black soldiers were generally assigned the nastiest camp duties and forced to confront the reality of racism on a daily basis.

RELATED

Unequal pay was one more glaring reminder of their second-rate status in the Union Army. A white enlisted man received $13 a month, an amount equivalent to about $240 in 2013, and his pay included a clothing allowance of $3, to be spent at the soldier’s discretion. A black enlistee was paid $10, but received only $7; the remaining $3 was withheld as a clothing allowance.

The evolution of a policy with such disruptive potential for the Union’s deployment of black troops reveals a presidential administration that was often scrambling to respond to military necessity while trying to balance conflicting pressures from Radical Republicans and Peace Democrats. At the beginning of the war, few but the most ardent abolitionists advocated arming blacks to help quell the Southern rebellion. Frederick Douglass’ sarcastic lament that “colored men were good enough to fight under Washington, but they are not good enough to fight under McClellan” was far less reflective of popular opinion than a New York Express editorial in late 1861 arguing that “putting arms into the slaves’ hands would result in turning the “sympathies of all mankind” against the Union.

When Secretary of War Simon Cameron was offered 300 black volunteers to help defend the nation’s capital city during the conflict’s first weeks, he demurred, saying that “this Department has no intention at present to call into the services of the Government any colored soldiers.”

Intentions began to shift in the wake of the Union debacle at Manassas in late July 1861. By the end of that year, the New York Tribune, a leading Republican newspaper, supported the use of black troops, and in his annual report to Congress, Cameron recommended arming the contrabands flooding into Union camps. But Lincoln forced Cameron to excise this recommendation from his report, the first of the president’s many actions to rein in zealous administration officials or field commanders sympathetic to abolitionist aims and eager to enlist blacks.

Read more from HistoryNet:

- Abraham Lincoln meets Frederick Douglass

- First black colonel: Charles Young

- HistoryNet fact sheet: Harriet Tubma

Early in 1862, for example, the administration quashed efforts to recruit black troops by Union generals in Kansas and Louisiana. And when Maj. Gen. David Hunter began organizing a regiment drawn from freedmen on the Sea Islands of South Carolina in May, opposition from Washington as well as local resistance to his heavy-handed recruiting practices forced him to abandon his effort after three months.

Shortly thereafter, though, Lincoln had a change of heart. In mid-August he replaced Hunter with Brig. Gen. Rufus Saxton, a Medal of Honor recipient and abolitionist. On August 25, 1862, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton authorized Saxton to recruit 5,000 volunteers at Port Royal, S.C., to form the first federally sanctioned black regiments.

Stanton’s action was in response to twin pieces of legislation passed a month earlier: the Second Confiscation Act, which empowered the president to employ contrabands in the suppression of the rebellion “in such manner as he may judge best,” and the Militia Act, authorizing the enrollment of blacks for “any military or naval service for which they may be found competent.” In issuing his August order, Stanton dictated that the volunteers were “to be entitled to and receive the same pay and rations as are allowed by law to volunteers in the service.”

Unfortunately, however, the usually meticulous Stanton had made a mistake — an error that would go unnoticed for nine months and result in rancor among thousands of the Army’s black recruits.

In accordance with an administration policy that only white officers could command black troops, Saxton turned to an old friend, Massachusetts abolitionist Thomas Wentworth Higginson, to lead the new regiment. Over the following months, the two men engaged in an experiment. Working with an isolated population of freedmen at some distance from the most intense combat, they thoroughly drilled the new recruits, insisting on a level of preparedness for battle that would have been impossible under more exigent circumstances.

Higginson embraced his mission with characteristic enthusiasm and a somewhat exaggerated sense of larger purpose, writing in his journal, “The first man who organizes and commands a successful black regiment will perform the most important service in the history of the war.” After his troops had performed admirably in a series of small engagements, he suggested that “the fate of the whole movement for colored soldiers rested on the behavior of this one regiment.”

By the time Higginson wrote those words in May 1863, the “movement for colored soldiers” was well underway. On New Year’s Day, the Emancipation Proclamation had affirmed that persons previously held as slaves “will be received into the armed service of the United States.” Changes in public opinion suggested a growing comfort with the idea of black troops. “The day for raising a panic over Negro enlistment has passed,” wrote Whitelaw Reid in the Cincinnati Gazette, “and it … has passed as an accepted fact into the history of the war.”

Union soldiers also seemed increasingly open to accepting black comrades in arms. In the spring of 1863, an Illinois soldier wrote: “A year ago last January I didn’t like to hear anything of emancipation. Last fall, [I] accepted confiscation of rebels’ Negroes quietly. In January, [I] took to emancipation readily, and now … am becoming so [color] blind that I can’t see why they will not make soldiers.”

The 1860 census revealed that there were about 100,000 free black men and more than 500,000 male slaves of military age. While many of the latter remained behind Confederate lines, younger men who had survived an escape to federal lines made up an unusually high percentage of the contraband population. Lincoln clearly saw the value of these potential soldiers.

“The colored population is the great available and yet unavailed of force for restoring the Union,” the president wrote in a March 1863 letter. “The bare sight of fifty thousand armed and drilled black soldiers on the banks of the Mississippi would end the rebellion at once. And who doubts that we can present that sight, if we but take hold in earnest.”

The Lincoln administration finally took “hold in earnest” in late May, when Stanton created the Bureau of Colored Troops. The bureau’s head, Major Charles Foster, devised different regional recruiting strategies for filling the ranks of the U.S. Colored Troops. In New England and the Middle Atlantic, Foster delegated the authority to enlist black troops to state governments and to public and private organizations, such as the Union League in Philadelphia.

Resistance among state leaders in the Midwest limited recruiting efforts in that area, while recruiters along the Atlantic Coast and in the Mississippi River Valley relied on impressment. In the border states and those areas of the Confederacy controlled by Union forces, the military itself generally oversaw recruiting, drawing heavily from contraband camps.

“Recruits were taken wherever found,” noted one Maryland soldier. “The laborer in the field would throw down his hoe or quit his plow and march away with the guard, leaving his late owner looking after him in speechless amazement.” Robert Cowden, a Union recruiter in Memphis, described the transformation undergone by new recruits:

“The average plantation negro was a hard-looking specimen … [in] a close-fitting wool shirt, and pantaloons of homespun material. … The first pass made at him was with a pair of shears. … The next was to strip him of his filthy rags and burn them, and scour him thoroughly with soap and water. A clean new suit of army blue was now put on him, together with a full suite of military accoutrements, and a gun was placed in his hands, and, lo! He was completely metamorphosed.”

RELATED

When establishing the Bureau for Colored Troops, Stanton had asked the War Department’s solicitor, William Whiting, to review the question of the pay rate for black soldiers. Whiting came back with a ruling that the only legislation in effect, the 1862 Militia Act, clearly stated that “persons of African descent, who under this law shall be employed, shall receive ten dollars per month and one ration, three dollars of which monthly pay may be in clothing.” Stanton’s earlier promise of equal pay, the basis on which many blacks had enlisted, was now inoperative.

When the Militia Act was adopted in July 1862, a number of rationales were used to justify the pay differential. Skeptical that blacks would make good combat troops, Lincoln and others in his administration and Congress argued that African American recruits would be assigned to garrison rather than front-line duty. There, they would more easily evade capture by vengeful Confederate forces. Furthermore, freedmen were thought to have developed immunities that made it easier to handle garrison duty in the Deep South, due to years of exposure to the climate.

Others, including The New York World’s editorial writers, argued that pay equity would inflame the prejudices of white troops: “To claim that the indolent, servile negro is the equal in courage, enterprise and fire of the foremost race in all the world is a libel. … It is unjust in every way to the white soldier to put him on a level with the black.”

By the middle of 1863, however, these arguments had become less credible. Colonel Higginson’s 1st South Carolina Volunteers had carried out a number of small but successful actions along the southern Atlantic Coast. In the West, recently organized USCT units fought with distinction during the early stages of the siege of Port Hudson and at the Battle of Milliken’s Bend on June 7, 1863.

“The bravery of the blacks completely revolutionized the sentiment of the army with regard to the employment of negro troops,” Assistant Secretary of War Charles A. Dana reported to Stanton. “Having seen how they could fight, many were won over to arming them for the Union.” Unfortunately, Stanton had already moved to align administration policy with the 1862 Militia Act, issuing a June 4 order that “Persons of African descent who enlist … are entitled to ten dollars per month and one ration; three dollars of which monthly pay may be in clothing.”

The strategy of paying black troops less than their white counterparts pleased no one: Those it was meant to appease saw it for the sop it was, while both black troops and their white supporters resented it. When Ohio Governor David Tod questioned the War Department about the policy, Stanton suggested that “colored troops must trust to State contributions and the justice of Congress” for any additional pay. John Andrew’s response was thunderous. “For fear the uniform may dignify the enfranchised slave, or make the black man seem like a free citizen,” exclaimed the Massachusetts governor, “the government means to disgrace and degrade him, so that he may always be … ‘only a nigger.’”

When Andrew sought to make up the difference in pay for the 54th and 55th Massachusetts regiments from state funds, a regimental spokesman condemned the offer for advertising “us to the world as holding out for money and not from principle — that we sink our manhood in consideration of a few more dollars.” As dramatized in the film “Glory,” the Massachusetts regiments refused time and again to muster to receive pay.

For many, the pay differential represented real hardship. A correspondent to the Christian Recorder wrote: “When I was at home, I could make a living for my wife and my two little ones; but now that I am a soldier they must do the best they can or starve.” Another soldier, serving in the 8th USCT, wrote that his “wife and three little children at home, are … freezing and starving to death. She writes to me for aid, but I have nothing to send her.”

The white officers shared their troops’ dismay. Unequal pay, wrote Colonel Higginson of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, “has inflicted untold suffering, has impaired discipline, has relaxed loyalty, and has begun to implant a feeling of sullen distrust.”

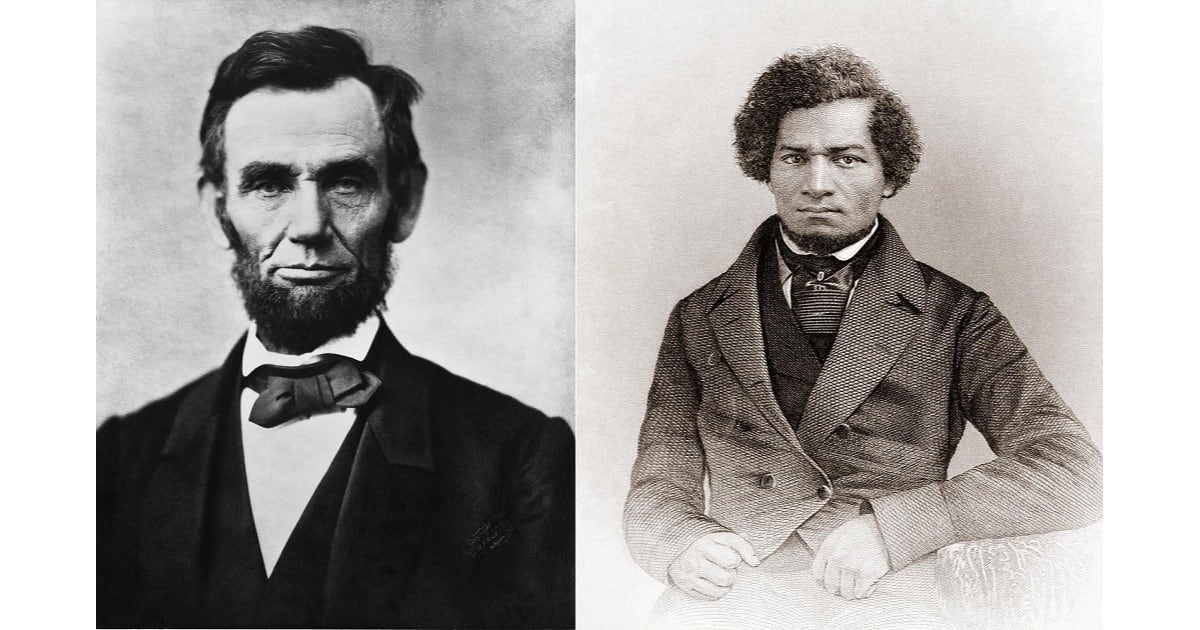

Black troops were not alone in harboring feelings of “sullen distrust.” On August 1, 1863, Frederick Douglass announced that he would no longer recruit troops for the Union Army. “When I plead for recruits, I want to do it with all my heart,” he wrote. “I cannot do that now.” George Stearns, a wealthy industrialist deeply involved in the recruitment effort, was reluctant to lose one of his most effective recruiters and urged Douglass to take his concerns directly to the president. On August 10, 1863, he did just that.

Arriving in Washington after a long train ride from Rochester, N.Y., Douglass set out on foot to see President Lincoln. Lacking an appointment, Douglass could not be sure that the president would even see him. A chance encounter with Samuel Pomeroy, a Radical Republican whom he knew well, led to an offer by the Kansas senator to help facilitate the meeting.

After a brief huddle in the War Department with Edwin Stanton, who assured Douglass that he favored equal pay, the abolitionist leader and his companion proceeded to the president’s house. To Douglass’ considerable surprise, the president received him almost immediately and put him at ease by assuring him that “I know who you are, Mr. Douglass; Mr. Seward has told me all about you.”

Although the two men had never met, Lincoln was well aware that Douglass was a frequent critic of his wartime policies as well as his support for colonization. So it was not surprising that Lincoln became somewhat defensive when Douglass raised one of his primary concerns — the pay inequity between white and black troops. “The employment of colored troops … could not have been successfully adopted at the beginning of the war,” argued the president. Although the wisdom of enlisting colored troops was still untested and was a “serious offense” to popular prejudice, Lincoln continued, black troops “had larger motives for being soldiers than white men” and “ought to be willing to enter the service upon any condition.” The fact that they received lower pay was a “necessary concession to smooth the way” and one that would ultimately be corrected.

“Not entirely satisfied with his views,” Douglass nonetheless “was so well satisfied with the man … that I determined to go on with the recruiting.” His audience led to no immediate change in the policy, but in his year-end report, Stanton did urge Congress to correct the pay differential.

The following June, Congress took the first step toward equalizing pay. Retroactive to January 1, all black troops were to be paid the same amount as their white counterparts. In addition, any member of the USCT who could attest that he had been a free man as of April 19, 1861, could collect back pay for 1862 and 1863.

Requests for back pay were to be accompanied by an oath, which led one creative colonel in the 54th Massachusetts to contrive a “Quaker oath” wherein claimants solemnly swore that they “owed no man unrequited labor on or before the 19th day of April, 1861.” While such a vow was plausible for a recruit from the Northern states, it would have proven patently false for the vast majority of the black troops, 75 percent of whom were recently freed slaves from the border states and Union-controlled portions of the Confederacy. Thus the issue continued to fester. Not until March 3, 1865, did Congress pass legislation granting full retroactive pay to all black units.

What took so long? Lincoln might well have reversed or simply chosen to ignore the ruling of either Stanton or the War Department’s solicitor in the spring of 1863. They had shown little reluctance, when they thought it necessary, to override other, more well-established policies or suspend vital constitutional rights.

For a contemporaneous example of the negligible impact of equal pay for black and white, they needed to look no further than the Union Navy, in which approximately 20 percent of the 101,000 men who served were black and received the same pay as their shipmates. In April 1864, Attorney General Edward Bates argued that the president had a “constitutional obligation” to rectify the pay inequity, but the president chose to leave the issue in the hands of Congress.

Lincoln’s rationale for failing to act sooner might perhaps be best divined from his August 1863 meeting with Douglass. The president comprehended that blacks “had larger motives for being soldiers than white men.” Had not Douglass himself argued that “there is no power on earth that can deny … the right to citizenship” to black men who fought for the Union? So Lincoln calculated that their eagerness to fight a war that would guarantee their freedom and lead to citizenship was likely to override any number of indignities suffered by black troops, including unequal pay. Lincoln’s embrace of this “necessary concession” proved in the end to be a sound calculation, but it came at no small price for William Walker and thousands of other African Americans who fought for the Union.

This article was originally published in the February 2014 issue of Civil War Times Magazine, a Military Times sister publication. For more information on Civil War Times Magazine and all of the HistoryNet publications, visit HistoryNet.com.