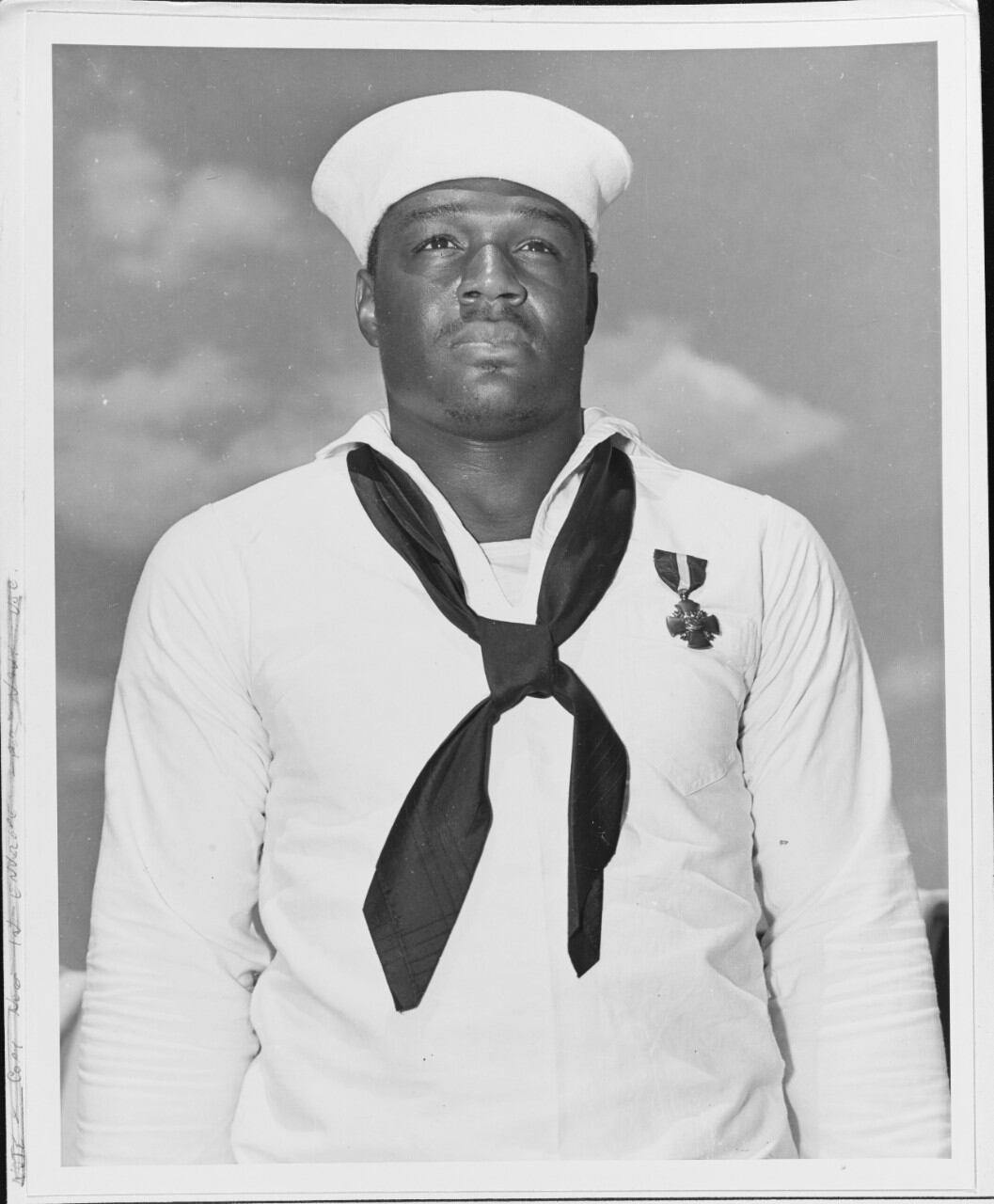

Among the pantheon of America’s heroes, none might seem more improbable than the black son of Texas sharecroppers and grandson of slaves, Doris Miller.

Miller, known to many as “Dorie,” was born on October 12, 1919, during the darkest days of the lynching epidemic that blighted the South in the 20th century’s first decades. Only three years before Miller was born, his hometown of Waco became the scene of one of the most brutal lynchings on record when 17-year-old Jesse Washington was burned alive on the lawn of the city hall.

Miller was compelled to drop out of high school in order to help support his struggling family — “We were a little hungry in those days,” his mother later explained — but when he could not find work, in September 1939, at 19, he joined the U.S. Navy.

At that time, black men serving in the Navy were not only ineligible for promotion, they were consigned to the lowly messman branch, where they were tasked with making the beds and shining the shoes of their white officers and waiting on them in the officers’ mess.

As one of Miller’s fellow messmen said, they were merely “seagoing bellhops, chambermaids, and dishwashers.”

By regulation, they could not be trained in or assigned to any other specialty, such as signals, engineering, or gunnery. Their battle station was below decks in the “hole” or magazine, where they passed ammunition up to the gunners.

They were not even allowed to wear buttons marked with the Navy’s insignia, an anchor entwined with a chain, and had to wear plain buttons instead.

But, said Miller, “it beats sitting around Waco working as a busboy, going nowhere.”

After attending a racially segregated boot camp at Norfolk, Virginia, he was assigned on Jan. 2, 1940, to the battleship West Virginia — which, due to the rising tensions between the United States and the growing Japanese empire, was soon transferred along with the entire Pacific Fleet to Pearl Harbor.

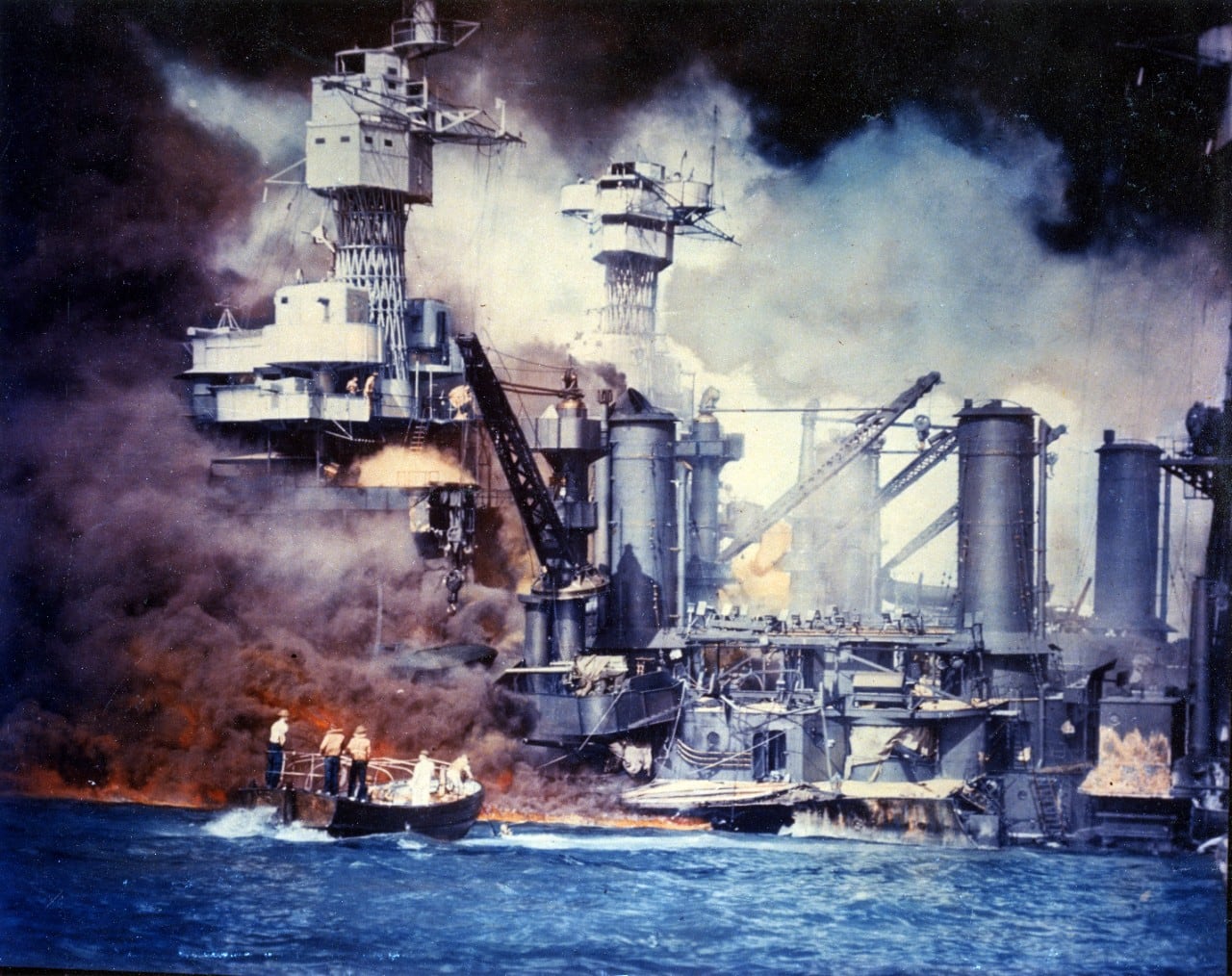

There, on the morning of Dec. 7, 1941, the fleet came under attack from carrier-launched aircraft of the Japanese Imperial Navy.

When the raid struck, Doris Miller — then 22 and a mess attendant third class — was below decks, doing the laundry of one of the ship’s ensigns.

With the first torpedo’s explosion, he reported to his battle station, the ship’s magazine. He found the magazine already flooded, however, and so went seeking reassignment.

He encountered the ship’s communications officer, Lt. Cmdr. Doir C. Johnson, who ordered him to the signals deck, where West Virginia’s commanding officer, Capt. Mervyn Sharp Bennion, lay mortally wounded.

Miller, the ship’s heavyweight boxing champion, was ordered to lift his dying captain and carry him to a place of relative safety, a sheltered spot just aft of the conning tower below the port side antiaircraft guns.

By then the ship had sustained heavy damage from two bombs and six Japanese torpedoes (a seventh failed to explode) and was listing drastically, its port guns silenced.

Most of its starboard guns were still operational, however, so Lt. j.g. Frederic H. White ordered Miller to start feeding ammo, packaged in 27-foot-long belts, to one of a pair of .50-caliber Browning machine guns that stood idly nearby, while White fired the gun at incoming Japanese planes.

The deck was awash with oil and water, and fires raged around him but Miller — finding the second gun unattended, and without orders and with absolutely no training in its operation — took control and opened fire.

“It wasn’t hard,” he later recounted. “I just pulled the trigger and she worked fine.”

White later reported that Miller “didn’t know very much about the machine gun, but I told him what to do and he went ahead and did it. He had a good eye.”

Lt. Cmdr. Johnson recalled Miller “blazing away as though he had fired one all his life.”

Miller himself stated that “when the Japanese bombers attacked my ship at Pearl Harbor I forgot all about the fact that I and other Negroes can be only messmen in the Navy and are not taught how to man an antiaircraft gun.”

Only when his gun ran out of ammunition and the critically damaged West Virginia began to sink did he cease firing, and only when Capt. Bennion was officially pronounced dead did the little group of officers and men abandon the ship’s bridge.

Descending to the boat deck, Miller helped pull sailors from the burning water, unquestionably saving the lives of a number of men. By then, the ship was flooded below decks and rapidly settling in the harbor’s shallow water, and its senior surviving officer gave the order to abandon ship.

Doris Miller was one of the last three men to leave West Virginia. He and his shipmates swam 300 or 400 yards to shore, avoiding patches of flaming oil from the battleship Arizona and strafing from Japanese planes.

Miller later told his brother that “with those bullets spattering all around me, it was by the grace of God that I never got a scratch.”

Even then, Miller helped scores of injured sailors to safety ashore.

Of West Virginia’s 1,541 crewmembers, 106 were killed and 52 wounded. Seven of the eight American battleships in the harbor that day were sunk or badly damaged.

Miller attributed his survival to divine providence: “It must have been on God’s strength and mother’s blessing,” he later told a newspaper reporter.

Considerable controversy still exists as to how effective Miller’s gunnery had been. Estimates — guesses, really — ran as high as half a dozen planes shot down, and his justifiably proud niece later made the claim that his gunnery had saved the U.S. West Coast from invasion that December.

But despite Miller’s best effort, just 29 of the 350 attacking Japanese aircraft failed to return to their carriers— and only one of those fell within the range of any of West Virginia’s guns.

Even that one, an Aichi D3A “Val” dive-bomber, was most likely struck by fire from West Virginia’s sister ship, Maryland, which was berthed forward of it, on the starboard side of Oklahoma.

According to an ensign, Victor Delano, who had been beside Miller on West Virginia’s bridge, “everyone else in the bay” had been shooting at the dive-bomber as well.

Said Lt. White, firing alongside Miller: “I certainly did not see him shoot down a plane.”

However many planes he may or may not have shot down, though, is beside the point: Doris Miller’s heroic actions at Pearl Harbor helped launch a revolution.

He deserves his niche in the pantheon of American heroes, for he provided an immeasurably important symbol for black Americans in their struggle for desegregation and equal opportunity — not only in the armed forces, but throughout the breadth of American society.

Within weeks of the disaster at Pearl Harbor, the Navy’s public relations officials released a number of stories, based on after-action reports of the attack, of heroism “equal to any in U.S. naval history.”

Those reports referenced the activities of an unknown black sailor, and hearsay stories soon began to circulate.

On Dec. 22, 1941, the New York Times printed a sketchy description related by an unidentified naval officer who supposedly served on the Arizona of a black sailor “who stood on the hot decks of his battleship and directed the fighting.”

This mess attendant, “who never before had fired a gun,” the story went, “manned a machine gun on the bridge until his ammunition was exhausted.”

This messman was added — though not by name — to the Navy’s 1941 Honor Roll of Race Relations.

On New Year’s Day 1942, the Navy released its list of commendations for heroism at Pearl Harbor. On the list was a single commendation for the still-unnamed black sailor.

When Miller’s mother heard the news of the black sailor who manned a machine gun, she was confident it was her son: “That’s got to be Doris they talking about,” she later told Texas historian R. Chris Santos.

Not until March 1942 did the Pittsburgh Courier, an influential African-American newspaper, release a story that at last identified the black messman as Miller.

Bills were quickly introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate to award Miller the Medal of Honor, but Georgia Democrat Carl Vinson, the House of Representatives’ Chairman of Naval Affairs, averred that Miller’s deeds were not deserving of the nation’s highest award for valor; Secretary of the Navy William Franklin Knox and the congressional delegation from Miller’s home state seconded him.

Both at the time and since, numerous historians and political leaders have argued that gallant as were the sacrifices of the 16 men—all of them white and most officers and petty officers — who were awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions that day, Dorie Miller’s exploits were at least of equal distinction, and all the more to be honored because of the oppressive racial stigma under which he performed so heroically.

While this controversy raged in the press, Miller, who had been assigned to the heavy cruiser Indianapolis on Dec. 13, 1941, was on duty in the South Pacific at a time of great shock and uncertainty.

“Mother, don’t worry about me and tell all my friends not to shed any tears for me,” he wrote home, “for when the dark clouds pass over, I’ll be back on the sunny side.”

But Miller’s occupational specialty remained in the messman branch and his battle station remained in the “hole,” handling ammunition.

In the States, politicians and journalists charged the Navy with foot-dragging and indifference to blacks in the armed forces, with Walter F. White, executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, pointing out that no citations had been awarded to black personnel “for acts of gallantry or heroism during the attack,” and urging President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Secretary Knox to grant official recognition to Miller.

“Without in any manner detracting from the heroism and gallantry under fire of white Americans who died at Pearl Harbor,” White urged, “the heroism of this Negro mess attendant merits special consideration.”

Due largely to Miller’s inspiration and under growing pressure to provide more equal opportunities for black recruits, Knox announced in April that “Negro recruits who volunteer for general service” would be trained at Camp Robert Smalls — an all-black section of the U.S. Naval Training Station at Great Lakes, Illinois — as gunner’s mates, quartermasters, radiomen, yeomen, boatswain’s mates, radar operators, and other specialties besides messmen.

And on May 11, President Roosevelt approved awarding Miller the Navy Cross—at the time, the third-highest Navy award for gallantry during combat.

It was the first such medal ever awarded to a black sailor.

On May 27, Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, the commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet, presented Miller with the Navy Cross on the flight deck of the aircraft carrier Enterprise.

Nimitz — also a native Texan — said then that Miller’s award “marks the first time in this conflict that such high tribute has been made in the Pacific Fleet to a member of his race, and I’m sure that the future will see others similarly honored for brave acts.”

The Pittsburgh Courier continued advocating for Miller, in June calling for him to be returned to the States for a war bond tour. The paper demanded that Secretary Knox order him home “so that he may perform the same service among his people that the white heroes are performing among their people.”

Wendell Willkie, the 1940 Republican nominee for president, and New York’s popular mayor, Fiorello La Guardia, also urged the Navy secretary to allow Miller to return on a war bond tour.

Miller himself was eager to make the trip. As he wrote to the Courier on Sept. 26, “I do hope your paper will continue the campaign in my behalf. It would be a great pleasure to get back for only a few days.”

The campaign bore fruit and Miller was ordered home. After nearly a year at sea, he arrived at Pearl Harbor on Nov. 23, 1942.

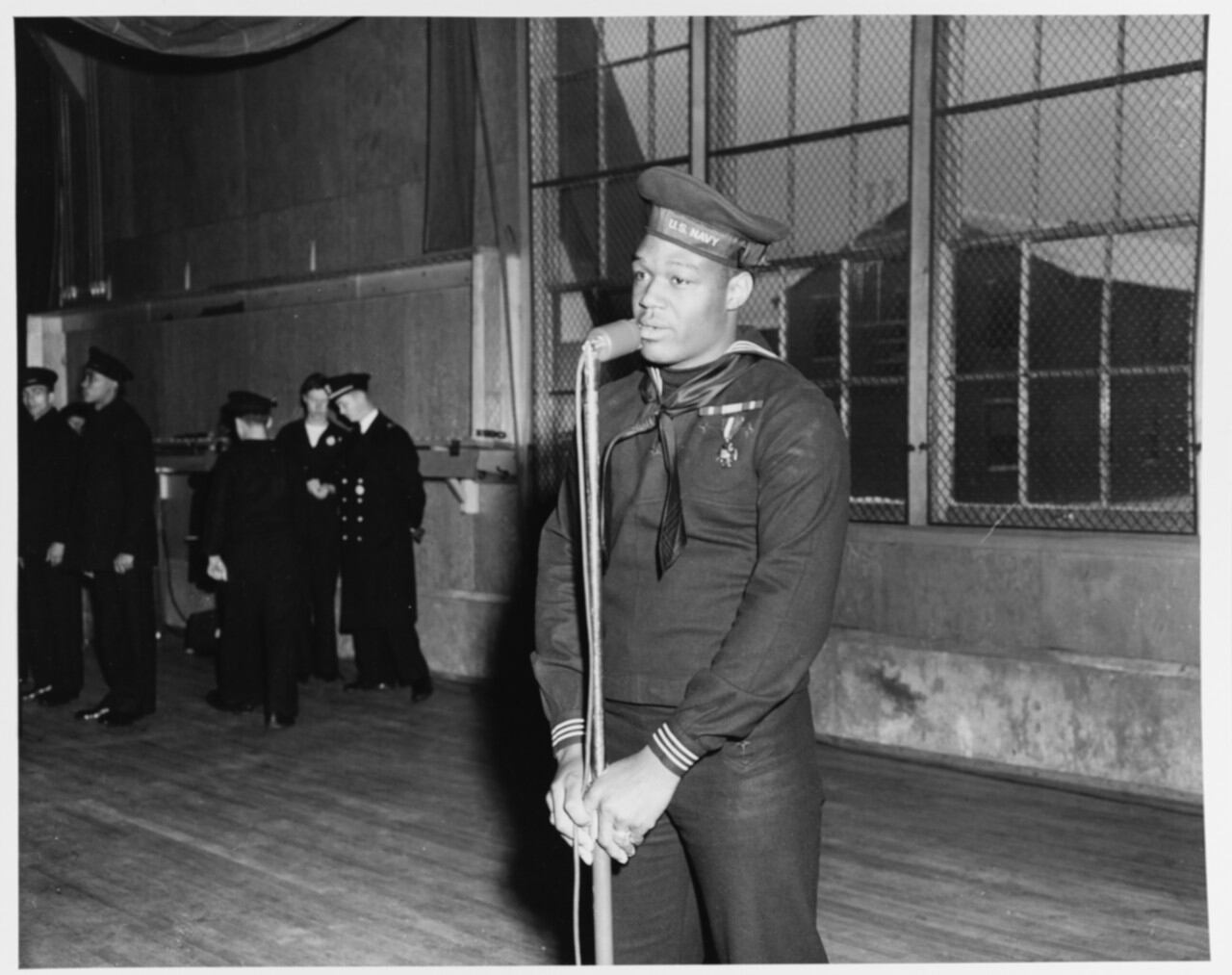

Over the course of the next two-plus months, Miller gave talks in Oakland, California; in his hometown of Waco, Texas; and in Dallas and Chicago, promoting war bond sales and accepting tokens of admiration from black communities.

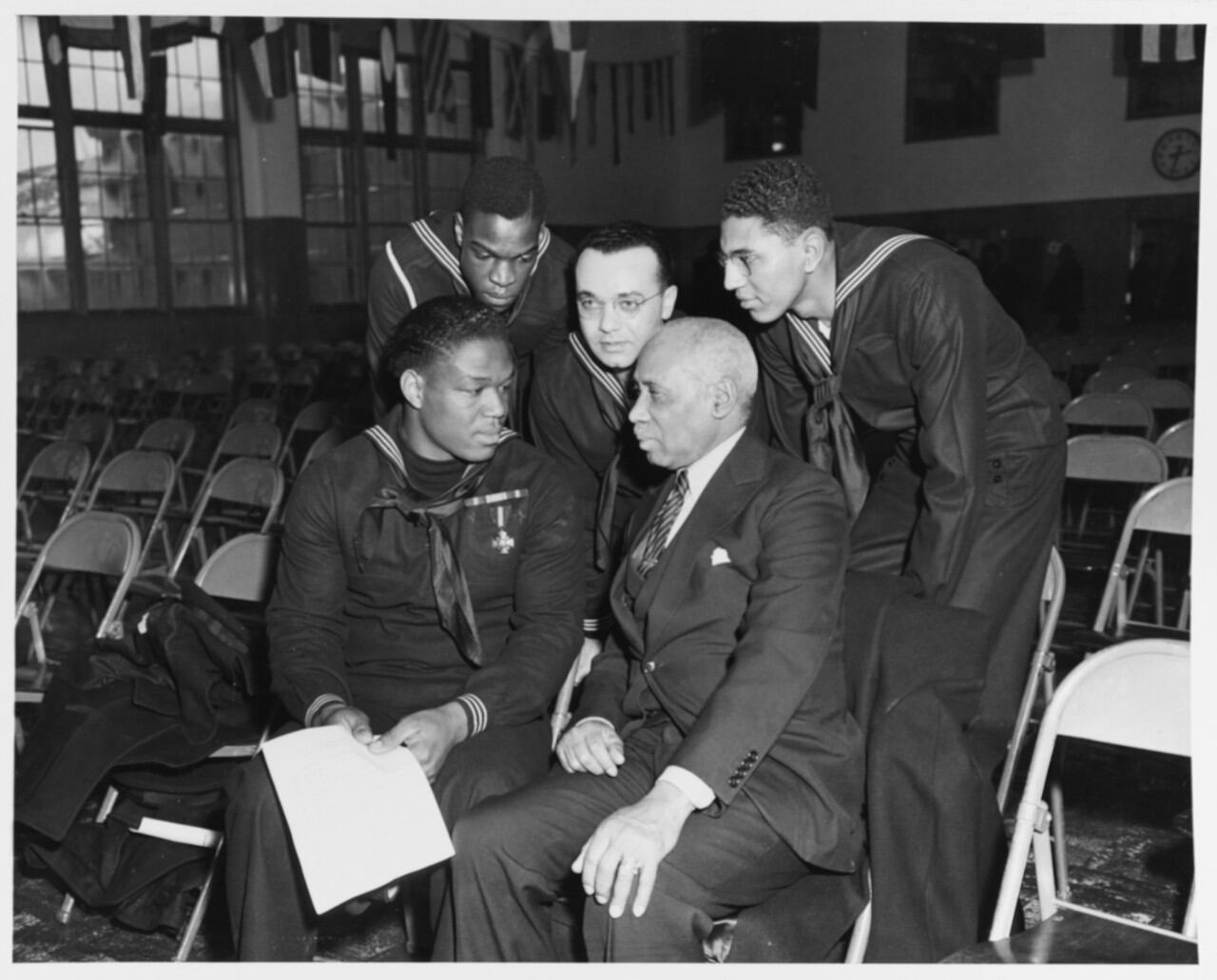

Perhaps most significantly, on Jan. 28, 1943, Miller addressed the first class of black sailors to graduate from Camp Robert Smalls.

The greatest honor that the Navy could pay Miller, the editor of the Pittsburgh Courier had written, “would be for it to abolish forthwith the restrictions now in force, so that black Americans can serve their country and their Navy in any capacity. This action by the Navy would not only reward a hero, but would serve dramatic notice that this country is in fact a democracy in an all-out war against anti-democratic forces.”

The focus of Miller’s talk at Camp Robert Smalls was the tremendous pride he felt in the Navy and of the privilege of being a part of it.

“It is almost unbelievable just what the perfect coordination and strength of our Navy actually is,” Miller told a reporter, and he urged the new sailors to “take advantage of their opportunities.”

While the revolution he had helped to inspire unfolded around him, Miller himself was transferred for reassignment.

On June 1, 1943, he arrived aboard the newly constructed escort carrier Liscome Bay as a mess attendant and was promoted to cook, third class.

His new ship was a CVE—a so-called “baby flattop.” Sailors sardonically claimed “CVE” stood for “Combustible, Vulnerable, and Expendable.”

Only two-thirds the length of such fleet carriers as the Enterprise, escort carriers were less expensive and more quickly built, but also relatively slow and less well-armed and armored.

Liscome Bay supported the Marine landings on Makin and Tarawa, pounding Japanese gun emplacements and air bases. With Thanksgiving approaching, Miller wrote to his mother that he did not expect the war to end soon but asked that she “prepare a place at the table for me in 1945. I will eat dinner with you all with a smile. Tell my friends to live the life that I am living.”

But on the early morning of Nov. 24, 1943, the ship’s lookout shouted, “Christ, here comes a torpedo!”

A single torpedo from Japanese submarine I-175 struck the carrier on the starboard side. Miller responded to general quarters, but a few moments later the ship’s aircraft bomb magazine exploded.

“We were hit just back of midship” and just aft of the engine compartment, recalled a survivor, Fireman 3rd Class Robert E. Haynes. “From here on back, everything was instantly gone.”

The thinly armored Liscome Bay carried more than 200,000 pounds of bombs, 120,000 gallons of bunker oil, many thousands of gallons of aviation fuel, and innumerable quantities of 20mm and 40mm cannon shells, all of which exploded.

Most of the crew died instantly, and Liscome Bay sank within 23 minutes.

The casualty list was among the largest of any Navy vessel in the war. Only 272 officers and enlisted men survived from the crew of more than 900.

Doris Miller was not among them. He was listed as “presumed dead” and after 365 days was reported as killed in action.

His body was never recovered.

RELATED

Target: Makin Island

Doris Miller’s death, however, was not in vain. The memory of his life has burned brightly as an example of how an underprivileged and oppressed young man from rural Texas can rise above poverty and racial discrimination — not only to display great courage, devotion, and patriotism, but to help alter the course of American history.

In January 1944, less than two months after his death, the Navy opened a modest officer-training program at Camp Robert Smalls for black sailors, commissioning its first 13 black officers on March 17, 1944.

Now, wrote one newspaper, “the heroic tradition of Dorie Miller at Pearl Harbor will serve as an everlasting inspiration” to every young man “to more fully serve his country and the Navy.”

On June 30, 1973, at the christening of the destroyer escort Miller — named in his honor — Texas Rep. Barbara Jordan predicted that the “Dorie Millers of the future will be captains as well as cooks.”

And, indeed, by this year, 2019, the U.S. Navy had eight black admirals in its ranks.

So how should Doris Miller be remembered?

Ronald Reagan did not get the facts exactly right when, in a 1975 speech, he regaled his audience with the story of “a Negro sailor whose total duties involved kitchen-type duties,” who shot down four dive-bombers with a borrowed machine gun. According to Reagan, Miller’s heroism single-handedly ended racial inequality in America.

“When the first bombs were dropped on Pearl Harbor,” Reagan intoned, “that was when segregation in the military forces came to an end.”

That, of course, was not true; important as they were, Doris Miller’s heroic actions on the day of the Pearl Harbor attack did not sound the death knell of racism in America.

But Miller’s heroism — and the legend it engendered — were directly responsible for helping to roll back the Navy’s policy of racial segregation and prejudice, and served as a powerful catalyst for the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s that brought an end to the worst of America’s racial intolerance.

As the Pittsburgh Courier proclaimed in 1956, Doris Miller had “died for his country so that his people might rise another notch in dignity and courage. Every blow struck for civil rights is a monument to [Dorie] Miller, citizen.”

This article was first published in the December issue of World War II, a sister magazine of Navy Times. Subscribe here.