In late August, as Hurricane Ida barreled toward Louisiana, nearly half of the Louisiana National Guard’s 256th Infantry Brigade Combat Team was deployed overseas, working in Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, and Syria. They’d been there nearly a year, having mobilized the previous fall — not long after responding to Hurricane Laura, which had tied a 144-year-old record for the strongest hurricane to make landfall in the state. Now, almost a year to the day later, Ida was expected to at least tie the record again.

The rest of the Louisiana National Guard had been mobilized ahead of the storm, along with guardsmen from 15 other states. Across the state, and from halfway around the world, soldiers waited for Ida to make landfall — not only to respond, but to see how their own communities would fare.

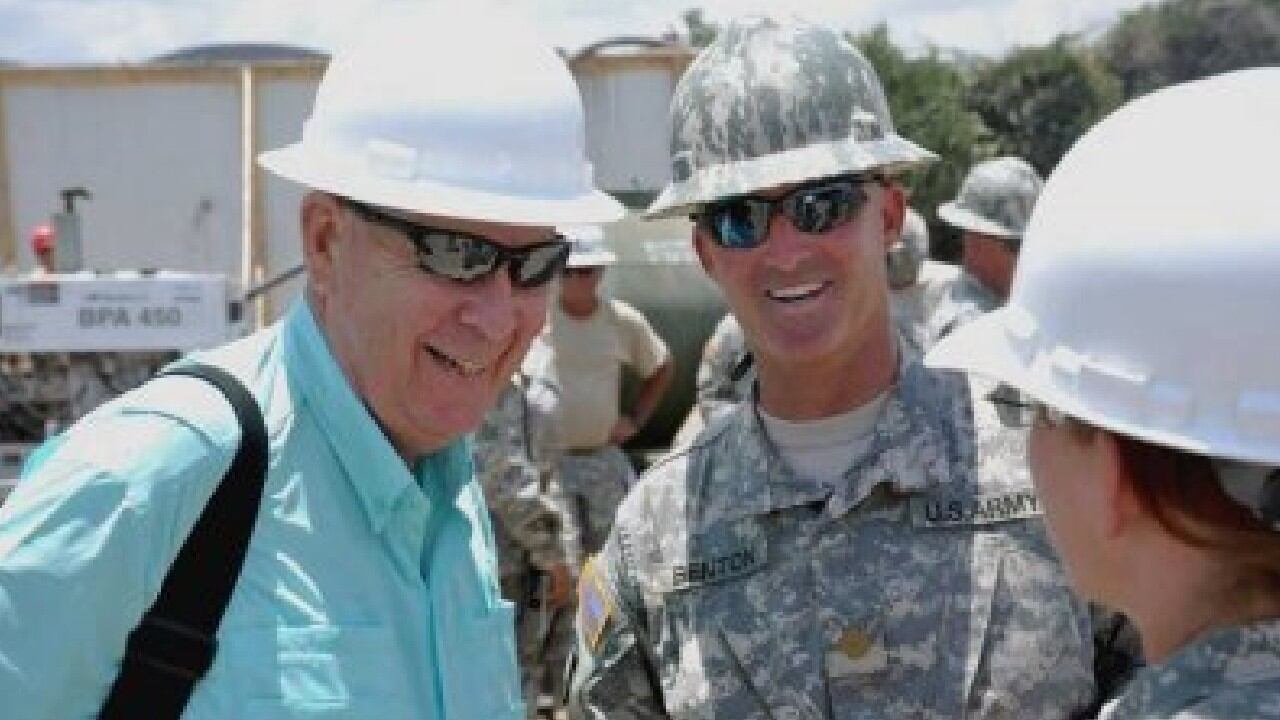

“I had two battalions’ worth of people, and many others in the state, that while they’re on duty, they’re also having to check on their own family and their own homes,” says Col. Larry Benton, the rear brigade commander for the 256th and the director of personnel and manpower for the Louisiana National Guard. Ultimately, he had to relieve more than 50 people from active duty — both in Louisiana and abroad — because of damage to their houses. “Their own homes were unlivable,” he says.

This is the new normal for the National Guard: The last two years have seen a rash of domestic crises — from the Covid-19 pandemic, to historic fires and flooding, to widespread protests — and guardsmen are often the first line of defense. Meanwhile, as the primary combat reserve of the Army and the Air Force, the guard regularly trains and deploys for overseas missions.

Two decades in Afghanistan and Iraq have proven the military’s essential reliance on its reserve forces. As the security landscape shifts from counterinsurgency and counterterrorism in Iraq and Afghanistan to competition with Russia and China, and as climate change wreaks havoc at home, and as the active forces face a potential drawdown, the guard and the reserves’ jack-of-all-trades skill set means they will be increasingly in demand, balancing new conflicts abroad and greater visibility at home.

“We’re moving from focusing on the conflict at this moment to thinking about how we shape or are ready for the conflicts that may occur in the future,” says Jacquelyn Schneider, a Hoover Fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institute. “How do we build a reserve that’s more flexible, that can be ready when we need it?”

‘That becomes everybody’s business’

For most of its history, the National Guard’s mission was focused primarily on the homefront — so much so that during the Vietnam War, joining the guard was considered a pretty safe strategy to avoid deployment. While the ploy didn’t always work — thousands of guard and reserve troops served in Vietnam — President Lyndon Johnson resisted pressure to mobilize the guard on a larger scale, worried that doing so would stir up even more anti-war sentiment and make political problems for him.

“Johnson, of course, wanted to fight this war on the quiet and on the cheap,” says Andrew Wiest, a professor of history at the University of Southern Mississippi and the founding director of the Dale Center for the Study of War and Society. “And if you mobilize the National Guard, then that suddenly becomes everybody’s business.”

But as the war wound down, and the end of the draft meant a drawdown in active troops, much of the support and logistics responsibilities for the Army shifted to the reserves. This trend was codified in 1973 as “Total Force Policy.” The policy officially designated the guard and the reserves as “the initial and primary augmentation of the active forces,” meaning that the Army’s full capabilities are spread between the active duty troops, and the reserves and the guard, which would train and surge as necessary — a cheaper alternative to maintaining a fully capable standing army. It also effectively ensured that any future major overseas engagements would require calling up the reserves.

Under the new policy, the reserves improved their training and readiness. But in the years after Vietnam, the concept of the reserves as an essential part of the United States’ warfighting capabilities remained more theory than practice.

“Here you have this guard that’s changed in idea and arguably changed in training somewhat, but hadn’t really faced the rubber meets the road,” Wiest says.

While National Guard units did serve in Desert Storm in 1991, it wasn’t until 9/11 — and the subsequent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan — that the military’s reliance on the reserves was put to the test. In the 20 years since 9/11, more than a million reservists have mobilized in support of global war on terror operations. Hundreds of thousands of reservists have served in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“All through the wars, they used reservists extensively,” says Mark Cancian, a senior adviser in the International Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. A retired Marine Corps reservist, he deployed twice to Iraq. “They’ve now become a standard part of our war-fighting capability.”

As the United States withdraws from Afghanistan, and the military’s attention turns to China and Russia, Cancian sees this reliance on the reserves continuing. In the Congressional Budget Office’s new report describing potential ways to operate with a smaller defense budget, all three proposed options “reduced only the full-time, active-duty force, leaving the reserve component untouched.” Why? Because the reserve component’s cheaper to operate and flexible enough to back up active-duty forces, if needed.

‘You’re going to be using a lot of reservists’

In the National Guard’s 2022 posture statement, Gen. Daniel Hokanson, the chief of the National Guard Bureau, highlighted the importance of training for war. “Given the uncertain future and budget priorities, we expect the Department of Defense to rely on the National Guard more, not less. Therefore, we must be ready to execute our three core missions: fighting America’s wars; securing the homeland; and building enduring partnerships that support our nation’s strategic objectives,” he wrote.

The last National Defense Strategy Summary specifically emphasized the importance of preparing for war with a high-tech, well-equipped adversary, as opposed to fighting insurgents. Cancian points to a need here for traditional warfighting skills — “tanks, planes, and ships,” as he puts it.

“Ninety-nine percent of what [the guard and the reserves] do are these traditional kinds of capabilities,” Cancian says. “If there were conflict in Europe against Russia, or conflict in the Western Pacific against China, or North Korea — pick your crisis spot, you’re going to be using a lot of reservists.”

But other skills, like cyber expertise, will come into play as well in the new security landscape. Nearly 4,000 Army and Air National Guard members in 40 states serve in cyber units, which have forged strong partnerships with state and local authorities who rely on their capabilities. In the last two years, for example, the Louisiana National Guard has helped respond to 90 cyber attacks in the state.

The guard has also advocated for the creation of a Space National Guard to align with Space Force, which would provide funding and resources, including for work the Air National Guard already does. Nearly 2,000 guardsmen work in specialized space units, according to the National Guard Association, and the guard provides 60 percent of Space Force’s offensive electronic warfare capability, as well as a third of the country’s strategic missile warning systems.

“The National Guard brings skills to play that will be incredibly valuable in this Swiss army knife kind of military atmosphere,” Wiest says.

‘The guard has had a tough two years’

Over the last two years, the National Guard’s “Swiss army knife” capabilities were on display somewhere else: back home.

“I think, for many years, we just ignored a lot of the domestic roles of the guard,” says Stanford’s Schneider. “We’re like, ‘Oh, there’s a hurricane. We’ll throw them in.’” But the layers of crises in 2020 and 2021 have highlighted just how much the nation relies on the National Guard to respond to domestic emergencies.

When the pandemic hit last year, and state guards mobilized, they were tasked with a wide array of missions: staffing testing sites, building field hospitals, ferrying supplies around states, manning foodbanks, and later assisting with vaccine efforts.

There were also more unusual missions. Army North’s Task Force 46, which is primarily staffed by members of the Michigan National Guard, is responsible for responding to chemical, biological, and nuclear threats in the United States, which requires close training and cooperation with state and local authorities, as well as federal agencies like FEMA. When COVID-19 arrived, the task force canceled its annual exercise and instead deployed across the nation, working with FEMA to coordinate the military’s response to the pandemic. More recently, Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker announced in September he was mobilizing the guard to help fill a shortage of school bus drivers caused by the pandemic and the resulting economic turmoil. New York Gov. Kathy Hochul floated a similar idea to fill potential healthcare worker shortages in the face of a vaccine mandate.

The pandemic was just the beginning. Wildfires in the west, flooding in the east, and extreme cold in the south mean that states’ guards are mobilizing regularly, either at home or in support of other states. Guardsmen have also deployed to the southern border, helped resettle Afghan refugees, even served as poll workers in last year’s election. Moreover, the protests over racial injustice that spread across the country in the summer of 2020 meant even more guardsmen were activated for crowd control and civil disturbances. In June of that year, at the height of the protests, more than 120,000 National Guard troops were mobilized, either at home or abroad. That’s more than at any point since World War II.

“The guard has had a tough two years,” Schneider says.

‘What we have to do is be prepared’

The guard’s dual mission at home and abroad means that equipment and training that can pull double-duty is particularly important. Federal missions — which often mean war, or training for it — come first, but the logistics, skills, and structure needed in domestic emergency response can mirror those on the battlefield, or in an overseas humanitarian response. Things like setting up a security perimeter, clearing a route, or moving into an area quickly and setting up shop have some basic similarities, whether troops are fighting insurgents in Afghanistan, responding to an earthquake in Haiti, or preparing for a hurricane in New Orleans, Benton says.

“The template that says, ‘Build the tents, bring the shower, and have the portalets,’ can be a mobile hospital, or it can be an engineer village for a levee breach, or it could be any security mission,” Benton says. “Those templates don’t change. Those become muscle memory.”

The same thing goes for equipment. Both the guard and the reserves prize gear that can be used at war or in a domestic emergency — everything from aircraft and cargo trucks to things like bulk water tank racks. The Army’s modernization priorities focus on air and land combat equipment and soldier lethality. According to a recent DOD report, the Army Guard’s air and weapons capabilities are generally more modern, in keeping with these priorities. Areas like engineering, logistics, and transportation, which are critical for responding to natural disasters, have more older equipment or shortages of this dual-use gear, the report says. But as Covid continues to surge, and climate change brings more extreme weather, the guard’s domestic missions, and its reliance on gear like this, are unlikely to abate.

At a briefing at the Pentagon last June, Hokanson acknowledged the historic year for the guard.

“Whatever the mission — combat deployments, Covid, wildfires, civil disturbances, or severe storms — the National Guard answered every call in 2020 and 2021, as we have for the past 384 years,” he said. “When we look at the future, however, we’re not really sure what it’s going to look like, but what we have to do is be prepared to meet whatever that demand signal is.”

‘Our demand signal is much, much higher’

One challenge the National Guard faces is that the demand signal — and the strain of service — isn’t borne equally. Coastal states are more likely to flood; wildfires are more likely in western states. Some states have strong traditions of guard service, while in others the footprint is much smaller. California, for instance, where the National Guard has helped battle wildfire after historic wildfire, has one of the lowest ratios per capita of guardsmen in the country.

“So we have to manage our mission sets very carefully,” Major General David Baldwin, the adjutant general of the California National Guard, told reporters in January.

“And we’re in a state that is constantly in a state of emergency,” he said. “So our demand signal is much, much higher.”

The National Guard tries to offset this issue with mutual assistance compacts and by planning ahead. For years, the guard has met annually to review training and deployment schedules and develop contingency plans for hurricane season. This year, for the first time, they did the same thing with wildfires. In states with high operational tempos, commanders have worked to help soldiers balance military service with family obligations and civilian careers. Some guard leaders have said the demands of the last two years, and the difficulty of maintaining this balance, shows that the service could be bigger.

“People are relying on us for more and more mission sets,” Baldwin told reporters. “To that end, the guard is not big enough and we need to grow.” Additionally, Hokanson is pushing for free health care for guard members, telling legislators last spring that it was his top legislative priority. A bill to that effect, the Healthcare for Our Troops Act, has been introduced in Congress.

And while balancing military service with a civilian career can be difficult, it’s also an area where the reserves see a potential benefit. Particularly in high-skill areas, like space and cyber, reservists can bring expertise from their civilian jobs to their military experience.

Schneider sees an even greater role for this sort of crossover between the civilian and military sides of reservist life.

“I think the focus should be on how do we build this talent pool?” Schneider says. “We didn’t expect the pandemic to happen, but wouldn’t it be nice if we had invested in our active-standby list, so that we had a better understanding of who are our epidemiologists, who are our nurses. In the future, there’s going to be skills that we just didn’t even anticipate.”

If there’s anything the last two years have shown, it’s that anticipating the future is both critical and incredibly tough. After recounting months of overseas deployments, mobilizations at home, and four hurricanes hitting the state, the Louisiana National Guard’s Benton described both a challenge and a chance.

“For the last year, this has probably been the most difficult opportunity for us,” he says.

Future years are likely to hold even more difficult opportunities, particularly as climate change continues. Domestic emergencies may mean communities become more aware of the National Guard and the breadth of the challenges they respond to—as well as the tension that can come with fighting conflicts abroad while under siege at home.

But Benton says tough times only increase his troops’ commitment.

“Our mantra is ‘Protect what matters,’” he says. “Our desire to protect what matters is what keeps us going.”

This War Horse feature was reported by Sonner Kehrt, edited by Kelly Kennedy, fact-checked by Ben Kalin, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar.

Sonner Kehrt is a journalist in California. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Wired Magazine, The Verge, and other publications. She studied government at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy and served for five years as a Coast Guard officer before earning a master’s in democracy studies from Georgetown University and a master’s of journalism degree from UC Berkeley.