Yoshio Nakamura remembers Dec. 7, 1941 in vivid detail. The panic of a nation. The cries for revenge and anger of his neighbors. The sentiments boiled within him, too.

But “Yosh,” as he likes to be called, also recalls the subsequent rage directed at people who looked like him. The suspicions that followed that day of infamy. The eventual order to leave his home.

That dreaded notice arrived in May 1942. Yosh was a junior in high school in El Monte, California. Just months earlier, inside the walls of that blissfully isolated existence unique to teenage academia, his classmates had elected him president of the school’s honor club.

None of that mattered to those who didn’t know Yosh. Outsiders didn’t see an artist, a farmer, a family-oriented kid. No amount of good standing made a difference once Executive Order 9066 was dispatched from the desk of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

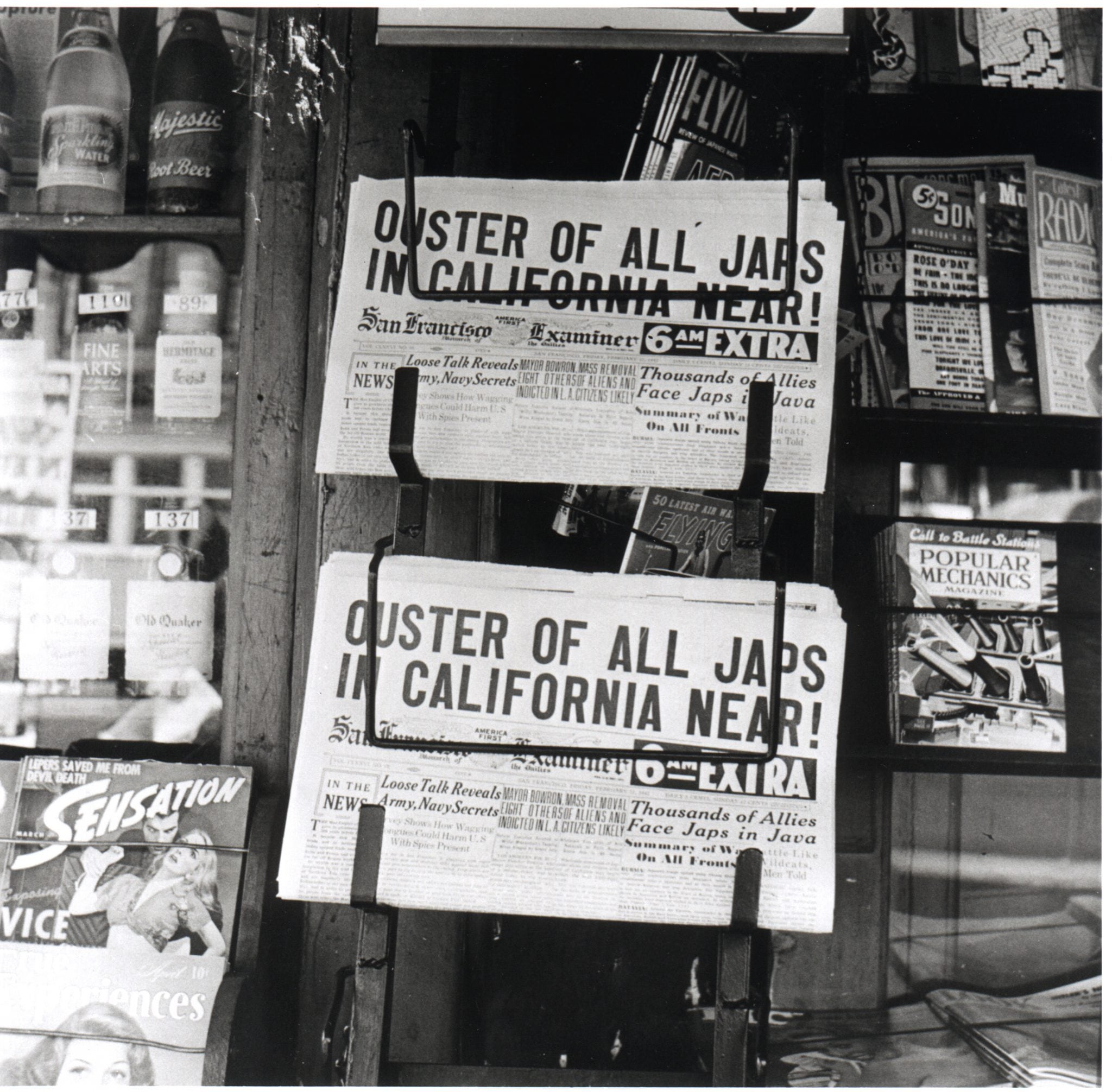

Fear and anger incited by politicians and media in the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor spawned rumors. Rumors were quickly accepted as truth. Japan must be receiving intelligence from spies in America. An illuminated light on a Japanese-American porch has to be a signal for enemy submarines. It all seemed so believable. How else could a small nation like Japan attack a titan?

“Many people stopped seeing the difference between Japanese-Americans and the enemy,” says Nakamura, now 97. “There was no exception. If you happen to have any Japanese blood, you were guilty. But we were just as shocked and angry as anyone else. We had Japanese faces, but American hearts.”

Under the charge of Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt, the executive order, one issued under the guise of safeguarding national security, was carried out up and down the Pacific coastline.

First generation—Issei—and second generation—Nisei, or, U.S. citizens by birthright—individuals of Japanese descent were removed from their homes en masse and ordered to report to assembly centers to await further instruction.

Packing only what they could carry, the Nakamuras departed their California farm and boarded a train for an unknown destination. Hours elapsed before the locomotive screeched to a halt in Tulare.

The streets surrounding the train station were a sea of dejected faces, families torn from the only homes they’d known. Nakamura’s family was ushered toward the town’s fairgrounds between a gauntlet of soldiers with rifles and bayonets at the ready. The race track was encircled with barbed wire. Guard towers stood at intervals. Search lights and sentries oscillated between each.

“It was probably the most humiliating experience of my life,” Nakamura says. “We had done nothing wrong, we weren’t charged with anything, and yet we were being treated like prisoners of war. The soldiers said they were there to protect us, but every search light and soldier faced in toward the camp instead of away from it.

“They called it an ‘assembly center.’ That was a nice name for a prison.”

Though their waiting period at the Tulare fairgrounds would be brief, the Nakamura family would never be the same.

Sleeping on cots in horse stalls that had been repurposed into living quarters, Nakamura’s father, who had begun suffering from night terrors, fell from his cot during one of the family’s first nights away from home. For the rest of his life, the elder Nakamura would be hampered by frequent convulsions that made even the simplest task impossible.

“He just wasn’t himself anymore,” says Yosh, whose mother died when he was seven. “We’d lost our farm and our father. We just had to manage the best we could.”

Weeks after being abruptly uprooted, the Nakamuras were ordered to Arizona’s Gila River War Relocation Center — ”another prison,” Yosh says.

It was one of 10 such camps that dotted desolate regions in California, Arizona, Wyoming, and Colorado, among others. It would be inside Gila River’s barbed wire boundaries, which held approximately 10,000 Japanese-Americans, that the honor club president would complete his high school studies.

Loyalty

Shortly after celebrating his 18th birthday in confinement, Nakamura and other young men at Gila River were ordered to fill out a loyalty questionnaire. Among the form’s myriad queries was one particular question that asked whether those in captivity would renounce their allegiance to the emperor of Japan.

“There was no right answer to that,” Yosh says. “If you answered yes, then it was like admitting you did have allegiance. And of course if you answered no...

“So many of us had never even been to Japan, but that questionnaire showed the mentality of the people who put us in camps. Because we have these faces, we must be loyal to the emperor.”

Nakamura checked ‘Yes.’

“It seemed to be the better of the two answers,” he says, laughing.

Yosh’s eyes then scanned toward another section of the form. Would he be willing to join the U.S. military and go wherever ordered?

“I don’t know many who would answer ‘yes’ to that question while being imprisoned without any charge by the government that’s asking,” he says. “But we did. We wanted to prove that we were loyal Americans.”

By 1944, Nakamura was a soldier in France, arriving as a replacement in the U.S. Army’s famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team, an unfathomably decorated outfit made up almost entirely of soldiers of Japanese descent, including Medal of Honor recipient and eventual Hawaii state Senator Daniel Inouye.

Nakamura’s stint in France would be a brief one, however. The Italian Campaign beckoned, and within months, Yosh and other members of the 442nd were boarding landing crafts destined for Leghorn, Italy, where they were to hurl lead and flesh against the Nazis’ daunting Gothic Line, an interlocked series of staunch defenses woven across the sawtoothed Apennine Mountains in the country’s northwest.

Embedded among those steep marble sentinels jutting skyward from the Ligurian Sea were nearly 2,400 machine gun nests, an interminable network of bunkers and artillery positions, and observation posts that allowed the Nazis to track enemy movements from miles away. Together, the fortifications formed the last barrier between the Allies and Germany.

The 442nd was given the order to attack the Gothic Line during the first week of April 1945. Yosh and the Nisei in his company were to take Monte Folgorito, a slick 3,000-foot peak peppered with Nazi dugouts and outposts.

Natural conditions — the mountain ascends at a 60-degree incline — meant a daytime assault would be virtually impossible. With the disadvantage of the escarpments, the 442nd were ordered to attack under the cover of nightfall. Silence was paramount.

In total darkness the Nisei climbed, lugging gear and ammunition with painstaking care to avoid rousing an unsuspecting enemy. One soldier slipped, plummeting 300 feet to his death. He didn’t make a sound.

“If we had engaged the Nazis before we got to the top, I probably wouldn’t be here,” recalls Nakamura, who was tasked during the assault with shouldering ammunition for his mortar company.

“It had to be done very quietly.”

By the morning of April 5, the 442nd’s cloak-and-dagger approach had landed the Nisei on Folgorito’s summit. Below them, the backs of Nazis ripe for the picking.

“We made it to the top and surprised the outposts and managed to knock out quite a good number of them in just a half-hour,” Yosh says.

The panicked Nazis responded with a hailstorm of mortar and artillery fire so intense that Yosh’s hearing never fully recovered. But the resolute soldiers with “Go For Broke” as their motto only tightened their stranglehold on the mountain, meticulously eliminating Nazis bunker by bunker and carving a path for the Allied advance into Germany.

“Unless we had wiped out those outposts, Allied forces could not have advanced North,” Yosh says. “I was very pleased to learn later that it was a major campaign.”

By April 6, the Nisei had seized the bulk of the Apennine Mountains. A little over a month later, Germany surrendered.

Yosh’s war abroad was over. The Nisei’s fight at home was drawing to a long-awaited close as well. In March 1946, the last remaining internment camp closed. Today, the Bronze Star Medal Yosh keeps on display remains a tangible testament to the loyalty his country once doubted.

Following the collapse of the Third Reich, the weary men of the 442nd boarded a ship and steamed for New York City.

Seeing the Statue of Liberty appear as a speck on the horizon was “probably the happiest scene I’ve ever experienced,” Yosh says.

‘A lot to be proud of’

Yosh left the Army in 1946 as a staff sergeant and turned his attention to academia. An art degree from the University of Southern California soon followed, as did a high school teaching position in Whittier, California, just miles from where his high school education was cut abruptly short years earlier.

Nakamura met his wife Grace in 1948 while attending a church service. Members of the congregation were heading to the beach. Yosh decided to offer her a ride.

Grace, whose family was forced during the war to relocate to the Manzanar internment camp in Inyo County, happily accepted.

“That was the beginning of a pretty good friendship,” Yosh says.

In the classroom, Nakamura’s rapport with his students quickly caught the eye of regional school administrators, who, by the early 1960s, charted a course for Yosh to become the founding chair of the Fine Arts Department at Rio Hondo College in Los Angeles.

The quick-witted veteran now jokes that his “academic and professional career is more interesting than my life before, even as a soldier.”

“I find myself spending more time talking about my experiences as a soldier because that’s what people want to hear, but I’ve really had a terrific life as an educator and artist,” he says.

On the 34th anniversary of Roosevelt’s directive, President Gerald Ford signed a proclamation terminating Executive Order 9066. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, authorizing a compensatory sum to be paid out as a formal apology to more than 100,000 people of Japanese descent who had been forced into internment camps. Just over two decades later, President Barack Obama authorized the award of the Congressional Gold Medal to the Nisei soldiers of the 442nd.

Yoshio and Grace, a community activist, educator and artist, remained married until her passing in 2017. They had three children — an attorney, an educator and an artist, appropriately.

Grace’s memory weighed heavily on Yosh earlier this year, when he joined the National Park Service at the site of the Manzanar camp, where she had been detained, in recognition of the 80th anniversary of Executive Order 9066.

“I missed her, because she would really be interested in this,” he says, adding, with a laugh, “and she probably would want to say a few things, too.”

Asked if he would want to say anything on behalf of Japanese-Americans in her stead, Yosh pauses briefly. A career as an educator has instilled in him a diligence to be concise.

“Japanese-Americans and Asian-Americans should be proud of who they are,” he says. “We were incarcerated, but we joined to fight and became one of the most highly decorated units in U.S. military history.

“That’s a lot to be proud of.”

Editor’s note: The 442nd Regimental Combat Team remains the most decorated unit in U.S. military history according to its size and length of service. In less than two years, the Nisei earned 21 Medals of Honor, 52 Distinguished Service Crosses, 560 Silver Stars, 22 Legion of Merit Medals, and more than 4,000 Purple Hearts, among other awards.

J.D. Simkins is the executive editor of Military Times and Defense News, and a Marine Corps veteran of the Iraq War.