When Thomas Johnson graduated from high school, going to an Ivy League university didn’t seem like an option.

Sure, he made good grades. But the idea of getting accepted into one of the eight elite Northeastern schools felt “like a real far reach.”

“There was that kind of stigma that you don’t have the ability to (get in) with such low acceptance rates,” Johnson, 25, said in a recent interview. “It was an obstacle that I didn’t think I could overcome.”

Johnson decided to join the Army instead and later earned an associate degree from a local community college.

Just last year, this would’ve made Johnson ineligible for admission to Princeton University, where he and five other students with military backgrounds who already have some college education will start classes Wednesday.

But the Ivy League school recently reversed its long-standing ban on transfer student admissions, in part to be able to enroll more veterans, who often earn college credit during their military careers. This marks the latest in a string of efforts by Ivy League institutions to make their campuses more accessible to veterans and, ultimately, grow the number of former service members within their ranks.

Rapid growth

In the last five fiscal years, the number of Post-9/11 GI Bill users at Ivy League institutions has grown nearly 34 percent, according to the Department of Veterans Affairs.

While the number of GI Bill users includes dependents using transferred benefits, as well as veterans, that VA data is the most accurate way to track veterans in higher education, since the large majority of GI Bill users are veterans.

Part of the reason for the enrollment growth at Ivies is the generous and relatively new Post-9/11 GI Bill itself, which covers up to $23,671.94 in tuition and fees per year at private schools and includes a sizable housing stipend. Schools can also choose to participate in the Yellow Ribbon program to defray additional costs not covered by the benefit, and according to VA records, all the Ivies do.

There are now roughly 1,700 GI Bill users at Ivy League schools — a far cry from the 206 enrolled a decade ago.

Schools have also ramped up their undergraduate recruitment efforts in that time, a move that is a bit unusual for campuses that are in no way hurting for applicants, said James Schmeling, executive vice president of the nonprofit Student Veterans of America. And with research demonstrating veterans do well in higher education, both veterans and schools now feel more confident about the value that former service members can bring to a top-tier institution.

“When both of those know better what is possible, then you’re going to get people into those schools,” Schmeling said.

A new approach

Since Princeton began rethinking its nearly 30-year ban on transfer students, the school has recruited on military bases, at student veteran conferences and through veterans groups at community colleges, said Janet Rapelye, Princeton’s dean of admission.

In fiscal 2017, Princeton enrolled just 22 GI Bill users — the fewest of any Ivy League school, according to VA data. But the school hopes its new policies and recruiting efforts lead to a turnaround.

“Without the transfer option, if they’d taken college courses, they simply couldn’t apply,” Rapelye said. “It just limited the pool so much.”

But there’s more to it than just recruitment. All applications, especially those of veteran and transfer students, are weighed for the life experiences that prospective students would bring to campus.

That’s an approach long taken at Columbia University, which has been recruiting service members and veterans to its School of General Studies, geared toward nontraditional students, since the early 2000s. Columbia enrolled 531 GI Bill users in fiscal 2017, the most of any Ivy League school.

“It’s great that universities are now beginning to value the experiences of service members and then also (beginning) to figure out how to value the academic potential of service members who don’t necessarily fit into the traditional ways of assessing academic intelligence or potential,” said Michael Abrams, executive director of the Center for Veteran Transition and Integration at Columbia.

While veterans may not always come with glowing GPAs or SAT scores, for example, they may have learned three languages in four years while on active duty. This is proof that they have the intelligence and the stamina it takes to succeed in a rigorous academic program.

“It’s really looking at other ways of assessing potential,” Abrams said.

Getting in and fitting in

“I think if you would ask any Marine, any airman, any sailor — you ask them, ‘Do you know that you could apply to these schools and you could have a chance to get in?’ they would probably tell you, ‘No, you’re crazy,’” said Marine Sgt. Javier Castillo, 22, “That’s what I thought.”

But Castillo, a first-generation immigrant born to Mexican parents who is also the first in his family to attend college, was accepted into both Columbia and the University of Pennsylvania.

“The fact that I’m going to be attending an Ivy League school is unheard of, at least for me,” said Castillo, who is starting classes at the University of Pennsylvania this fall as he transitions out of the military.

Castillo isn’t alone.

Andrea Goldstein, CEO of Service to School, an organization that helps veterans get into top-tier schools, said they’re generally not accustomed to bragging about themselves or discussing details about their service.

“We’re taught selfless service and not to advertise the nature of our work, and so to suddenly have to talk about yourself — and not only talk about yourself but say why you should be admitted to a program — is very tough,” said Goldstein, a Navy veteran and reservist.

Through mentorship, admissions counseling and other help, Goldstein said, her organization helps build that confidence so veterans know they can succeed at these schools.

“That’s a lot of what we’re about,” she said. “We’re not just about letting people know that they can get it, we’re letting them know that they can fit in.”

Without Service to School, Johnson — and several other veterans who talked to Military Times for this story — say they wouldn’t have gotten into an Ivy.

Johnson said his Service to School advisor was the first one to tell him about Princeton’s transfer policy change and helped him apply.

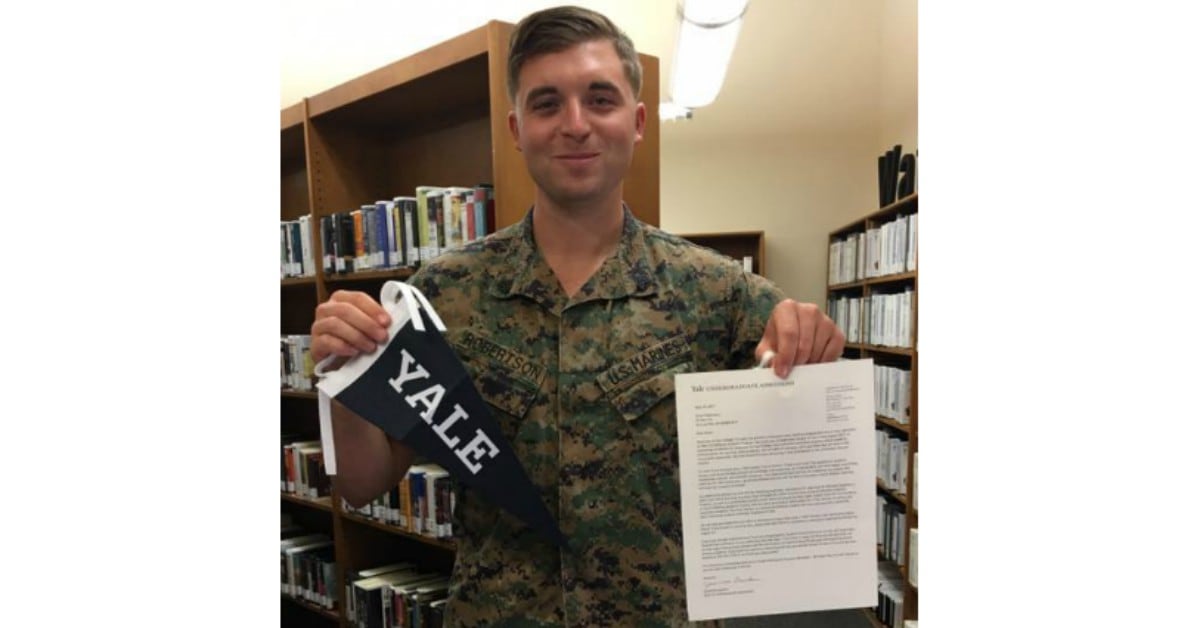

Summer Lee, a Marine veteran who’s now a junior at Yale University, said she’d never dreamed of attending a top-tier school, but with the group’s help, she ended up getting accepted to Yale, Brown, Cornell and Georgetown University.

Service to School has grown 20 to 30 percent each year since its founding in 2011, and the group helped 1,700 veterans apply to college last year, Goldstein said.

“We screen and prepare applicants, so (schools) know if they are getting a veteran student who is from Service to School that they are highly prepared,” she said.

Some Ivies are providing a little extra help in this department as well.

Cornell University recently launched a six-week Veterans Summer Bridge Program for both transfer and first-time students. The program includes three free, credit-bearing courses, including one focusing on strategies to succeed in college, offering student veterans a chance to get their feet wet before the fall semester.

This summer, the University of Pennsylvania hosted the Warrior-Scholar Project, a rigorous academic boot camp designed to prepare service members and veterans for college life.

“You literally have no time off. From the time you wake up, it’s books, writing, speaking on topics,” said Castillo, who participated in the training to get ready for the fall semester. “I think this is definitely beneficial just because they give you a taste of what it might be like at a top-tier institution.”

A ‘value proposition’

Goldstein said it’s ultimately a “value proposition” for colleges to enroll veterans. While, yes, veterans in many cases come fully funded or close to it with the GI Bill, it goes beyond money, she said.

They’re also going to add value to the classroom.

“I absolutely experienced this firsthand in one of my classes, where we were talking about security force assistance, training a foreign military,” she said. “It was one thing to talk about it from an academic perspective. It was another thing to hear about it from someone who had actually done it.”

Johnson said learning often happens through conversations in the classroom, which are enhanced by different viewpoints, such as those of veterans who have leadership experience and have lived through basic training, deployments and other major life changes.

“I think (what Ivy League schools) are really realizing — to bring that kind of diversity as far as viewpoints and ideas to the campus — is they have to expand the types of students they’re bringing in,” he said. Veterans "just bring a different set of ideas to the campus that might not otherwise be represented.”

Part of the unique perspective that Johnson will bring to Princeton: that of a new father. His wife is set to give birth to a baby girl this week, just as classes get underway.

“I was joking with my wife about a lot of these students that are coming in. They’re going to be dealing with being away from their family for the first time and dealing with a set of issues and things they have to overcome, and mine will be dealing with a brand new baby and a family,” he said.

But so far, Princeton has shown it will support him. The financial aid office offered assistance just as it would to any other student, despite him having the GI Bill, and he’s already received individualized attention through an online forum and pre-orientation with the other new transfers.

“All my college experience before this was community college,” he said. “There is a shift there, and Princeton has recognized that to make the transition as easy as possible.”

Military Times contributor and former reporter Natalie Gross hosts the Spouse Angle podcast. She grew up in a military family and has a master's degree in journalism from Georgetown University.