WASHINGTON — At a staging ground in Ghana, a group of nuclear experts watched the clock and nervously waited for the news.

The team — a mix of American, British, Norwegian and Chinese experts, along with Czech and Russian contractors — were supposed to head into the Kaduna region of Nigeria to remove highly enriched uranium from a research reactor that nonproliferation experts have long warned could be a target for terrorists hoping to get their hands on nuclear material.

But with the team assembled and ready to go on Oct. 20, 2018, the mission was suddenly paused, with the regional governor declaring a curfew after regional violence left dozens dead. As American diplomats raced to ensure the carefully calibrated window of opportunity didn’t shut, the inspectors were unsure if the situation would be safe enough to complete the mission.

“Frankly speaking, yeah, I was nervous for my people on the ground and everyone else who was on the ground. It was important, but we had to go at it in a prudent way” said Peter Hanlon, assistant deputy administrator for material management and minimization, an office within the U.S. National Nuclear Security Administration. “As someone responsible for this organization, I was nervous.”

Moving the nuclear material out of Nigeria has been a long-sought goal for the United States and nonproliferation advocates. But the goal has taken on increased importance in recent years with the rise of militant groups in the region, particularly Boko Haram, a group the Pentagon calls a major terrorist concern in the region.

Underscoring the importance of the operation: the key role China played in transporting and storing the uranium, with the operation happening just hours after U.S. President Donald Trump made an explicit threat to China about growing America’s nuclear arsenal.

For those gathered in Ghana that evening, however, the focus was on watching the clock and hoping that the negotiators could come through and allow them to finally get the material out of Nigeria — and get everyone home safely.

‘Material that is attractive to terrorists’

It was the mid-1990s when Nigeria, with technical support and backing from China, began work on what would become Nigerian Research Reactor 1, located at Ahmadu Bello University in Kaduna. The location opened in 2004, and is home to roughly 170 Nigerian workers.

NIRR-1 is classified as a miniature neutron source reactor, designed for “scientific research, neutron activation analysis, education and training,” per the International Atomic Energy Agency. Essentially, the reactor powers scientific experiments, not the local grid.

The design, however, used highly enriched uranium, or HEU, a type of nuclear substance often referred to by the general public as weapons-grade uranium. This kind of uranium forms the core of any nuclear weapons material, and the Nigerian material was more than 90 percent enriched, making it particularly attractive for anyone looking to use it.

Since NIRR-1 went online, however, improvements in technology meant that experiments involving highly enriched uranium could now be run with a lesser substance. Across the globe, the IAEA and its partners have worked to swap out weapons-grade material with low enriched uranium, or LEU, which is enriched at less than 20 percent, and hence unusable for weapons. In all, 33 countries have now become free of HEU, including 11 countries in Africa.

With just over 1 kilogram of HEU, the Nigerian material, if stolen, would not be nearly enough to create a full nuclear warhead. However, a terrorist group would be able to create a dirty bomb with the substance or add the material into a stockpile gathered elsewhere to get close to the amount needed for a large explosion.

In a statement released by the IAEA, Yusuf Aminu Ahmed, director of the Nigerian Centre for Energy Research and Training, was blunt about his concerns over keeping the weapons-grade material in his country. “We don’t want any material that is attractive to terrorists," he said.

And the nature of these types of reactors, used primarily for research, means they are ideal targets for terrorist groups looking for nuclear material, said Jon Wolfsthal, a nuclear expert who served as senior director for arms control and nonproliferation at the U.S. National Security Council from 2014 to 2017.

“They’re small reactors, they’re not power reactors where the fuel is so radioactive it kills you,” he said. “This is very attractive to a proliferation point of view, and they are research reactors, so they are often at universities without high security.”

All of which gave the governments involved incentive to get the material out of Nigeria sooner rather than later, and which led to the group of experts sitting in Ghana, waiting for a call.

The day of

It wasn’t until Oct. 22 — two days after the initial delay — that American diplomats, working with their Nigerian counterparts, were able to get an exemption to the curfew in Kaduna and prepare to roll out. But for security reasons, an operation that usually took days would have to happen in just one 24-hour period.

At 1:30 a.m. on Oct. 23, a Russian Antonov An-124 cargo plane touched down in Nigeria. Aboard were the team of experts, but also a TUK-145/C — a 30-ton cargo container designed specifically for moving such uranium from place to place and doing so securely.

From the outside, the TUK-145/C looks like a large, silver cylinder, designed to keep its precious cargo safe even in the event of a plane crash — as part of the safety testing before certification, the container is put into a pool of jet fuel, with the whole thing then lit on fire for 60 minutes. If you somehow could cut it down the middle, the container would appear to be two parts — an outer shell for security, and an innermost cask containing the spent uranium rods.

Both the plane and the TUK-145/C are owned and operated by the Russian Sosny Research and Development Company, a specialty firm that has been used in other HEU removal procedures.

Loading the equipment off the plane took hours, as did the trip from the airstrip to the reactor. But finally, the team arrived at the reactor around 9 a.m. The group now included U.S. State Department security and Nigeria’s Army First Division, considered a top-end unit of the Nigerian military.

Tiffany Blanchard-Case, a nuclear expert from the National Nuclear Security Administration, was one of the officials on the ground to oversee the transfer. She described a “grueling” day as the team rushed to condense what needed to be done into the secure window.

“No one was concerned about breaks, no one was concerned about lunch, everyone was just working 100 percent in order to make sure we could meet this schedule,” she said. “A long day for everyone.”

Getting at the uranium is tricky business. The reactor core, which holds the actual material, is located at the bottom of a six-meter-deep pool. Above the pool, technicians have to create a platform and then center a vessel, known as the interim transfer cask, above the core. The cask contains a grapple, which reaches into the reactor and lifts out the core; when the core is loaded in, a plug is placed over the core and the cask is sealed, loaded onto the Skoda shipping cask, and then that unit is sealed inside the TUK-145/C.

Replacing HEU with LEU in research reactors naturally requires caution, as anything nuclear-related comes with risks. But the Nigerian mission was particularly difficult because of security concerns, Hanlon said. He noted that Boko Haram, while not in the Kaduna region, has been operating in Nigeria for quite some time.

“We had concerns about the security on the ground, in the region. Working very closely with the U.S. embassy, there were additional security requirements put upon us and limitations for us on having people on the ground at the facility itself,” Hanlon said.

Hanlon and Blanchard-Case declined to discuss details of the security, other than to say it was heavy and that the U.S. State Department added extra forces as part of the agreement to allow the team to go in.

Alice Hunt Friend, a regional expert with the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said that Boko Haram is not necessarily “active” in the region, but added that an attack by the group in that area shouldn’t be ruled out.

“The city is a transport hub, pretty much right between Abuja and Kano on the main route. It is also in the belt that has experienced a lot of communal violence over the past 10 years, so I can also imagine that security for HEU sites would be of concern more generally, even absent a specific threat,” she said. “With much of the Nigerian military concentrating on the northeast, I would imagine security for sites in Kaduna is inconsistent.”

Boko Haram is just one threat that worries security teams on the ground, said Peter Haynes, an analyst with the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments.

“Fueled by ethnic and religious differences, there has been lots of violence in the Kaduna region in the last six months, but that has been between Fulani Muslim herders and Christian villagers,” said Haynes, adding that it is not “uncommon as of late to have curfews to dampen the communal violence.”

While the technicians were able to leave the country once their daylong mission was complete, security on site remained thick for the next five weeks as administrators worked the logistics and clearances needed to fly nuclear material over other nations' airspace. Asked about the security level during this down period, Dov Schwartz, an NNSA spokesman, said that “extensive planning went into ensuring the removed highly enriched uranium was safe and secure prior to transport."

"All of our partners understood that operational security was paramount,” Schwartz said. "The world is a safer place today as a result of the determined work to remove this weapons useable Uranium from Nigeria.”

Finally, on Dec. 4, the HEU was escorted by the Nigerian military toward the An-124, loaded onto the aircraft and sent on its way to its final destination.

The material was heading for China.

China’s role

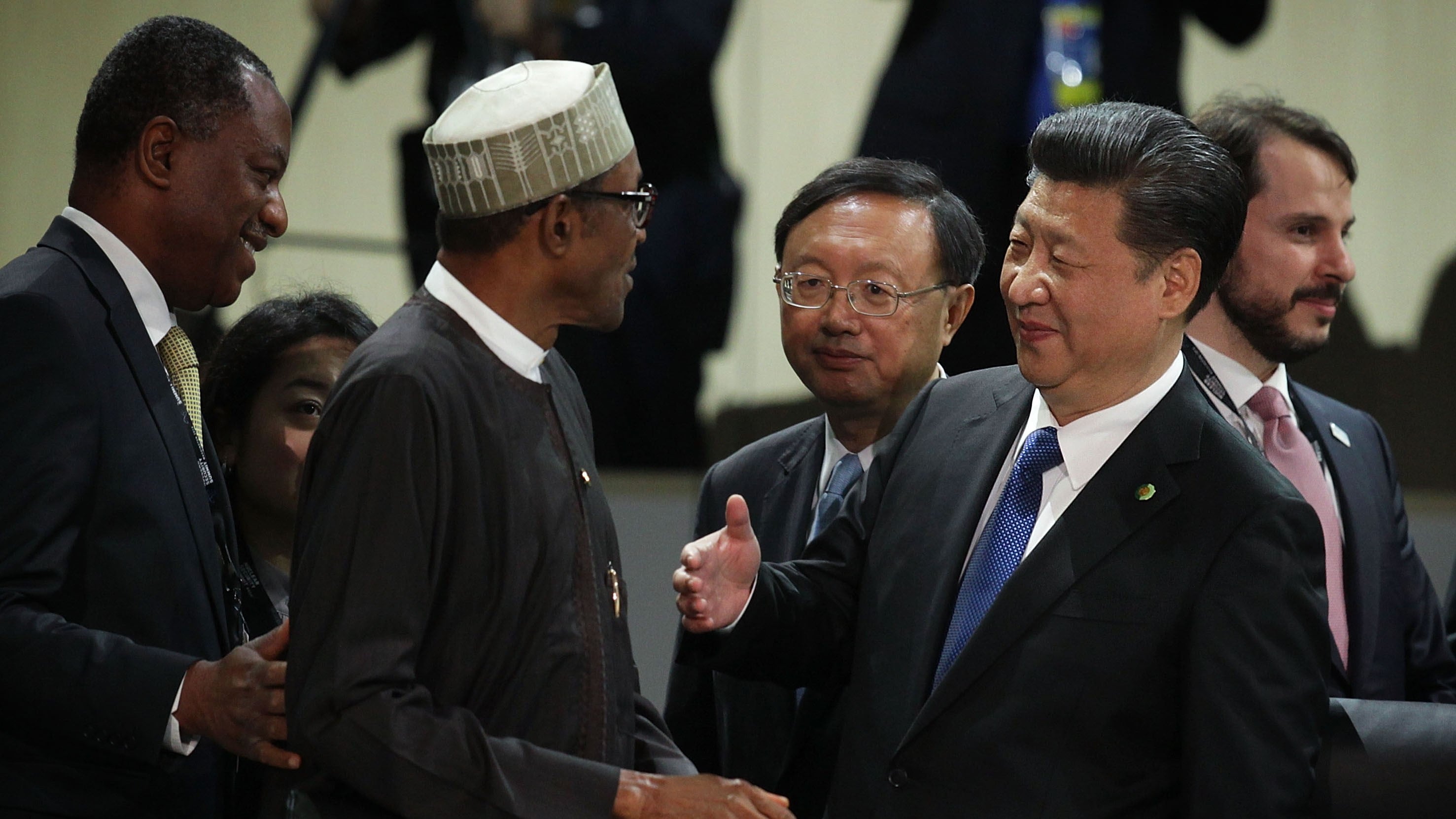

The removal operation cost roughly $5.5 million, with the United States contributing $4.3 million. The United Kingdom ($900,000) and Norway ($290,000) also chipped in. But while it didn’t contribute money, China’s role in the operation was outsized — and occurred as the war of words from the Trump administration toward Beijing was reaching a fever pitch, one that did not die down in the weeks to come.

As the October operation was just hours from starting, U.S. President Donald Trump took to the press to discuss nuclear material and China.

“Until people come to their senses, we will build [the nuclear arsenal] up," Trump told reporters just hours before the Nigeria operation was to begin. "It’s a threat to whoever you want. And it includes China, and it includes Russia, and it includes anybody else that wants to play that game. You can’t do that. You can’t play that game on me.”

By the time the Antonov plane — carrying the HEU, along with American inspectors and security — arrived at Shijiazhuang airport in China on Dec. 6, the arrest of a Chinese technology executive in Canada had inflamed fears of a trade conflict between the two countries.

Once the material landed in China, local officials took possession of the uranium, marking the end of the Nigerian mission — but not necessarily the end of the material.

Hanlon acknowledged the United States doesn’t know what China will do with the material, noting they could dispose of it in whatever way they see fit. But Wolfsthal, the former National Security Council staffer, doesn’t think Beijing will let it go to waste.

“My guess is China will reprocess it and then recycle some of the materials,” Wolfsthal said. “It could end up in China’s stockpile after being reprocessed, or used for civilian fuel. But getting it out of Nigeria is the biggest thing.”

In a statement released by the IAEA, Shen Lixin, deputy director general of the department of business development and international cooperation at the China National Nuclear Corporation, said the project “manifests the determination and joint effort of several governments and organizations in preventing nuclear proliferation."

“This is also a demonstration of CNNC’s meeting its social responsibilities and the commitment to peaceful uses of nuclear energy,” the statement continues. “CNNC is more than willing to work together and cooperate whole heartedly with relevant parties to facilitate other MNSR conversion projects.”

That the United States and China were able to ignore politics to get the HEU removal done shouldn’t be a surprise, Wolfsthal said. Traditionally, countries that supply uranium to partners around the world take that material back if needed.

“Even though the national level conversation is really poor because of trade and other issues, the technical collaboration between laboratories, between nuclear engineers, that’s generally gone pretty well,” he said. He added that China has invested heavily in LEU over the last decade, and therefore also has an interest in encouraging others to switch to that technology.

Whether that cooperation continues if relations between the two nations continue to deteriorate will be a true test going forward. On Jan. 3, the U.S. State Department issued a travel warning for China, urging American citizens to use caution when traveling, as the Chinese government may detain Americans.

And an agreement to develop new nuclear technology between CNNC and TerraPower, an American nuclear firm led by Microsoft founder Bill Gates, appears doomed due to American restrictions on technology sharing with China.

Hanlon, for his part, is optimistic that China and the U.S. will continue to work on nuclear security.

“These nuclear security efforts of removing this dangerous material, most countries agree with that,” he said. “That work has continued unabated.”

Aaron Mehta was deputy editor and senior Pentagon correspondent for Defense News, covering policy, strategy and acquisition at the highest levels of the Defense Department and its international partners.