The U.S. Army has hidden or downplayed the extent to which its firearms disappear, significantly understating losses and thefts even as some weapons are used in street crimes.

The Army’s pattern of secrecy and suppression dates back nearly a decade, when The Associated Press began investigating weapons accountability within the military. Officials fought the release of information for years, then offered misleading answers that contradict internal records.

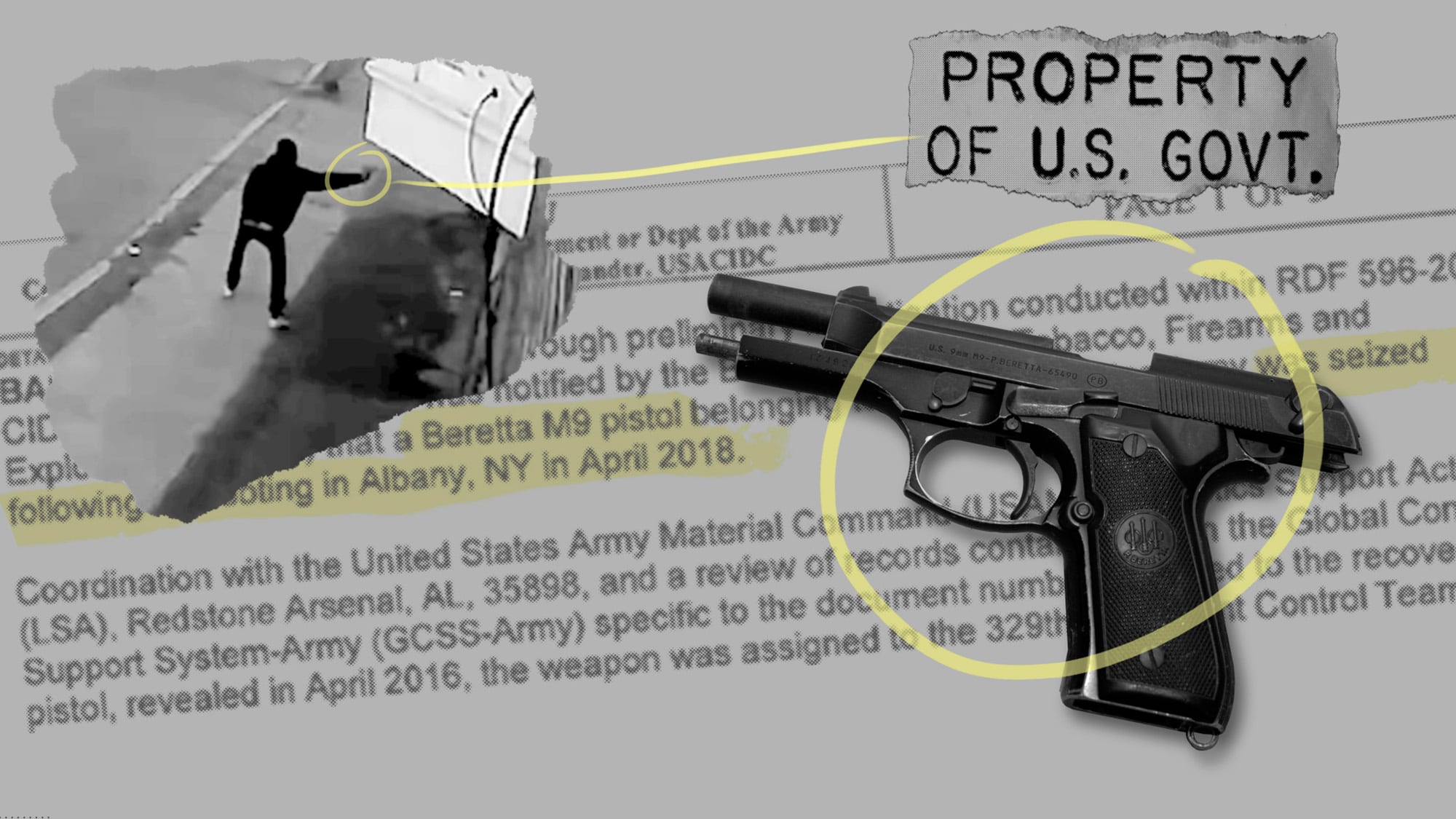

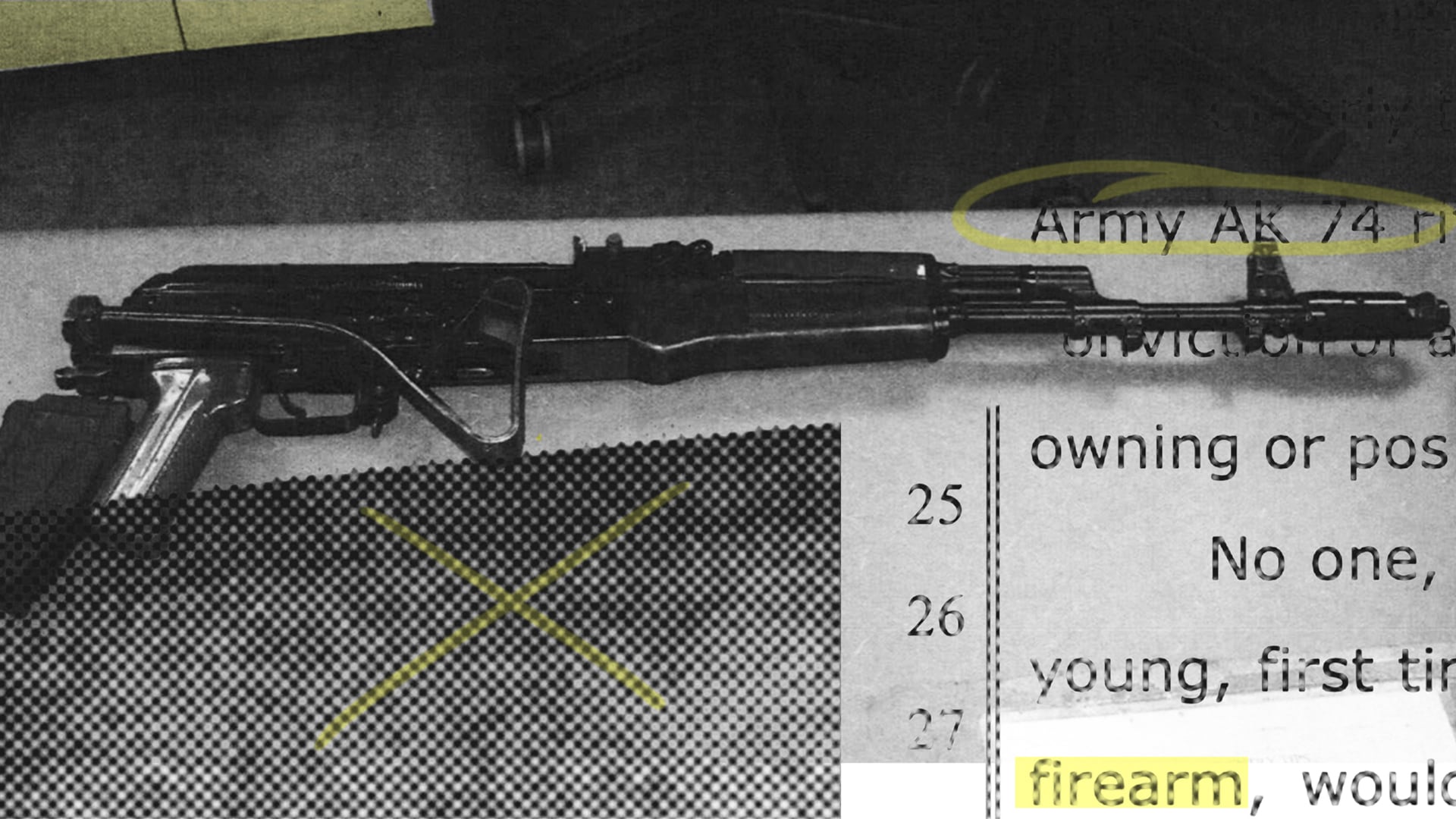

Military guns aren’t just disappearing. Stolen guns have been used in shootings, brandished to rob and threaten people and recovered in the hands of felons. Thieves sold assault rifles to a street gang.

Army officials cited information that suggests only a couple of hundred firearms vanished during the 2010s. Internal Army memos that AP obtained show losses many times higher.

Efforts to suppress information date to 2012, when AP filed a Freedom of Information Act request seeking records from a registry where all four armed services are supposed to report firearms loss or theft.

The former Army insider who oversaw this registry described how he pulled an accounting of the Army’s lost or stolen weapons, but learned later that his superiors blocked its release.

As AP continued to press for information, including through legal challenges, the Army produced a list of missing weapons that was so clearly incomplete officials later disavowed it. They then produced a second set of records that also did not give a full count.

RELATED

Secrecy surrounding a sensitive topic extends beyond the Army. The Air Force wouldn’t provide data on missing weapons, saying answers would have to await a federal records request AP filed 1.5 years ago.

The broader Department of Defense also has not released reports of weapons losses that it receives from the armed services. It would only provide approximate totals for two years of AP’s 2010 through 2019 study period.

The Pentagon stopped regularly sharing information about missing weapons with Congress years ago, apparently in the 1990s. Defense Department officials said they would still notify lawmakers if a theft or loss meets the definition of being “significant,” but no such notification has been made since at least 2017.

On Tuesday, when AP first published its investigation, Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., demanded during a Senate Armed Services Committee hearing that the Pentagon resurrect regular reporting. In a written statement to AP, the Pentagon said it “looks forward to continuing to work with Congress to ensure appropriate oversight.”

Blumenthal also challenged Army Secretary Christine Wormuth on her branch’s release of information.

“I’d be happy to look into how we’ve handled this issue,” Wormuth replied. She described herself as “open to” a new reporting requirement and said the number of military firearms obtained by civilians is likely small.

Poor record-keeping in the military’s vast inventory systems means lost or stolen guns can be listed on property records as safe. Security breakdowns were evident all the way down to individual units, which have destroyed records, falsified inventory checks and ignored procedures.

Brig. Gen. Duane Miller, the No. 2 law enforcement official in the Army, said that when a weapon does vanish the case is thoroughly investigated. He pointed out that weapons cases are a small fraction of the more than 10,000 felony cases Army investigators open each year.

RELATED

“I absolutely believe that the procedures we had in place absolutely mitigated any weapon from getting lost or stolen,” Miller said of his own experience as a commander. “But does it happen? It sure does.”

The Associated Press began investigating the loss and theft of military firearms by asking a simple question in 2011: How many guns are unaccounted for across the Army, Marines Corps, Navy and Air Force?

AP was told the answer could be found in the Department of Defense Small Arms and Light Weapons Registry. That centralized database, which the Army oversees, tracks the life cycle of rifles, pistols, shotguns, machine guns and more -- from supply depots to unit armories, through deployments, until the weapon is destroyed or sold.

Getting data from the registry, however, would require a formal Freedom of Information Act request.

That request, filed in 2012, came to Charles Royal, then the longtime Army civilian employee who was in charge of the registry at Redstone Arsenal in Alabama.

Royal was accustomed to inquiries. Military and civilian law enforcement agencies would call him thousands of times each year, often because they were looking for a military weapon or had recovered one.

In response to AP’s request, Royal pulled and double-checked data on missing weapons. Royal then showed the results to his boss, the deputy commander of his department.

“After he got it, he said, ‘We can’t be letting this out like this,’” said Royal, who retired in 2014, in an interview last year.

His boss didn’t say exactly why, but Royal said the release he prepared on weapons loss was heavily scrutinized within the Army.

“The numbers that we were going to give was going to kind of freak everybody out to a certain extent,” Royal said -- not just because they were firearms, but also because the military requires strict supervision of them.

AP was unable to reach Royal’s supervisor and an Army spokesman had no comment on the handling of the FOIA request.

RELATED

In 2013, the Army said it would not release any records. The AP appealed that decision and, nearly four years later, Army lawyers agreed that registry records should be public.

It wasn’t until 2019 that the Army released a small batch of data. The records from the registry showed 288 firearms over six years.

Though years in the making, the response was clearly incomplete.

Standing in the stacks at the public library in Decatur, Alabama, last fall, Royal reviewed the seven printed pages of records that Army eventually provided AP.

“This is worthless,” he said.

Told that in multiple years, the Army reported just a single missing weapon, Royal was skeptical. “Out of the millions that they handled, that’s wrong,” he said in a later interview. AP has appealed the FOIA release for a second time.

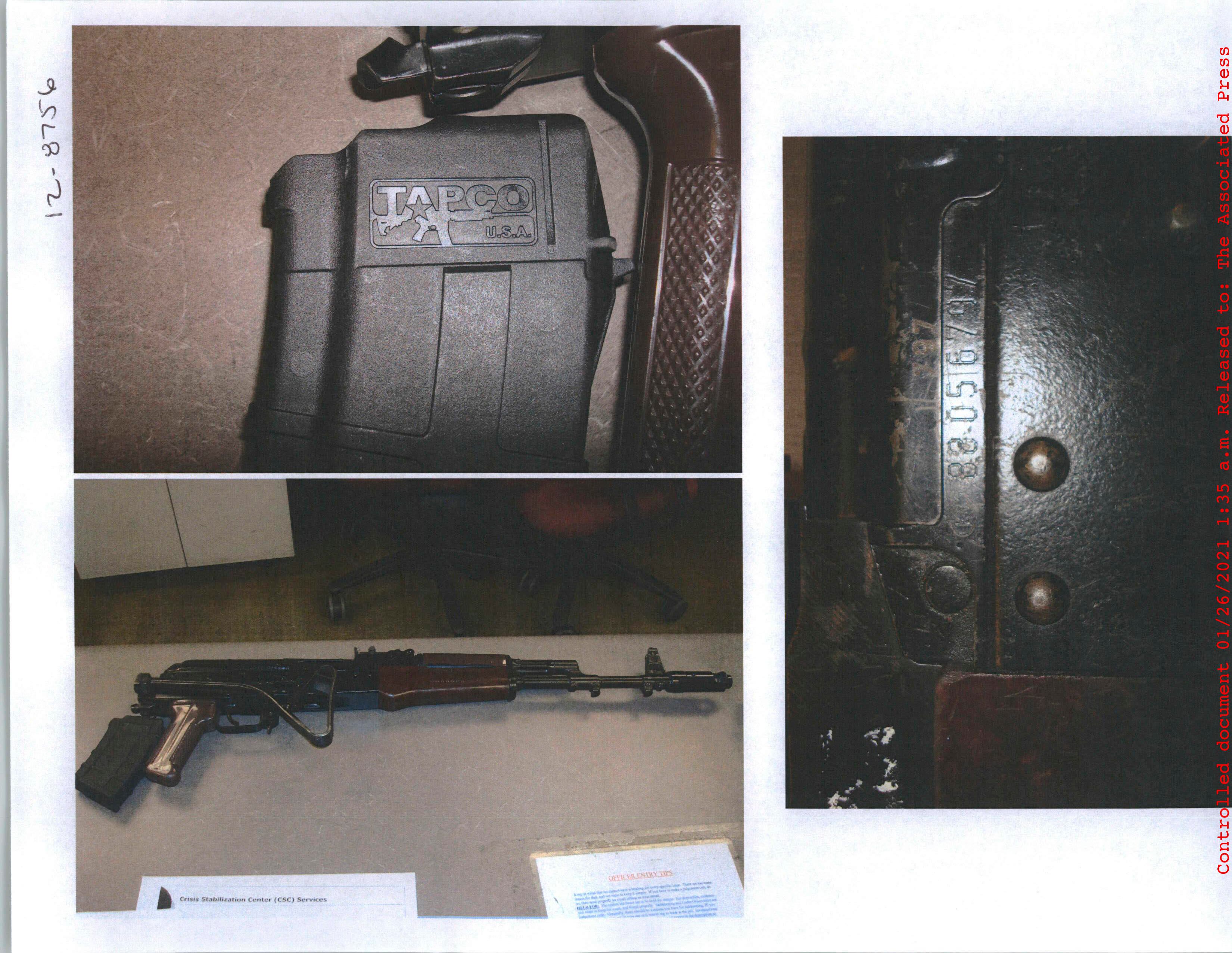

The data weren’t even accurate when compared to Army criminal investigation records. Using the unique serial numbers assigned to every weapon, AP identified 19 missing firearms that were not in the registry data. This included a M240B machine gun that an Army National Guard unit reported missing in Wyoming in 2014.

The Army could not explain the discrepancy.

Reporters also filed another records act request for criminal cases opened by Army investigators.

In response, Army’s Criminal Investigation Command produced summaries of closed investigations into missing or stolen weapons, weapons parts, explosives or ammunition.

Army spokesman Lt. Col. Brandon Kelley said that the records were “the Army’s most accurate list of physical losses.” Yet again, the total from the records provided -- 230 missing rifles or handguns during the 2010s -- was a clear undercount.

The records did not reflect several major closed cases and excluded open cases, which typically take years to finish. That meant any weapons investigators are actively trying to track down were not part of the total.

Army’s first two answers -- 288 and 230 -- are contradicted by an internal analysis, one that officials initially denied they had done.

Asked in an interview whether the Army analyzes trends of missing weapons, Miller said no -- there were breakdowns of murders, rapes and property crimes, but not weapons loss or theft.

“I don’t spend a lot of time tracking this data,” Miller said.

In fact, in 2019 and 2020, the Army distributed memos describing military weapons loss as having “the highest importance.” The numbers of missing “arms and arms components remain the same or increased” over the seven years covered by the memos, called ALARACTs.

A trend analysis in the document cited theft and “neglect” as the most common factors.

The memos counted 1,303 missing rifles and handguns from 2013-2019.

During the same seven years, the investigative records the Army said were authoritative showed 62 lost or stolen rifles or handguns.

Army officials said that some number they couldn’t specify were recovered among the 1,303. The data, which could include some combat losses and may include some duplications, came from criminal investigations and incident reports. The internal memos are not “an authoritative document,” and were not closely checked with public release in mind, Army spokesman Kelley said.

Members of Miller’s physical security division were tracking the data, though Miller said he wasn’t personally aware of the memos until AP brought them to his attention. He said that that if he were, he would have shared them.

“When one weapon is lost, I’m concerned. When 100 weapons are lost, I’m concerned. When 500 are lost, I’m concerned,” Miller said in a second interview.

Each armed service is supposed to inform the Office of the Secretary of Defense of losses or thefts. That office also has not released data to AP, but spokesman John Kirby gave approximate numbers of missing weapons for the past few years. The numbers were lower than AP’s totals.

“There is no effort to conceal,” Kirby said. “There is no effort to obstruct.”

Hall reported from Nashville, Tennessee; LaPorta reported from Boca Raton, Florida; Pritchard reported from Los Angeles. Also contributing were Lolita Baldor and Dan Huff in Washington; Brian Barrett in New York; and Justin Myers in Chicago.