This story is part of the portfolio that won the 2023 Society for Professional Journalists Dateline Award for beat reporting in a newsletter or trade publication.

The Air Force has spent the past four years making a concerted push to ready its planes for war. It’s gained almost no ground.

On average, seven out of every 10 planes were available as needed for combat missions, training or other routine operations last year, according to fiscal 2021 data the service provided to Air Force Times on Nov. 23.

Mission-capable rates, the main readiness metric across nearly 40 of the service’s major aircraft, remained essentially stagnant, from 72.7% in 2020 to 71.5% in 2021. It’s a meager bump from 2018, when it sank just below 70% — its lowest point in nearly a decade.

That status quo threatens the Air Force’s reliability not only in a crisis but also in its daily routine. It means the service is spending taxpayer dollars on inefficient maintenance practices and fleets — some of which are more than 50 years old — and that the service’s standoff with lawmakers, who typically reject plans to ditch outdated planes, will continue into fiscal 2023.

The Air Force takes a more optimistic view. Col. James Hartle, the service’s associate logistics director, said the force is getting close to where it needs to be on mission-capable rates, pointing to the intense two-week Afghanistan evacuation in August as evidence the people and planes can respond in a crisis.

“We are almost satisfied with the mission-capability rates,” Hartle told Air Force Times on Jan. 20. “We’ve got areas to improve, places that we can increase and opportunities to get those numbers up, but it takes a little bit of time.”

But in an extended conflict against a major adversary, rates in the low 70% range aren’t going to be enough, said Heritage Foundation defense expert and former fighter pilot John Venable.

“Think about running a war against Russia or China, where you’ve got to generate all of your aircraft in order to make that happen,” Venable said. “That math does not bode well.”

Which aircraft are mission-ready — which are unprepared?

The Air Force’s progress has been piecemeal at best.

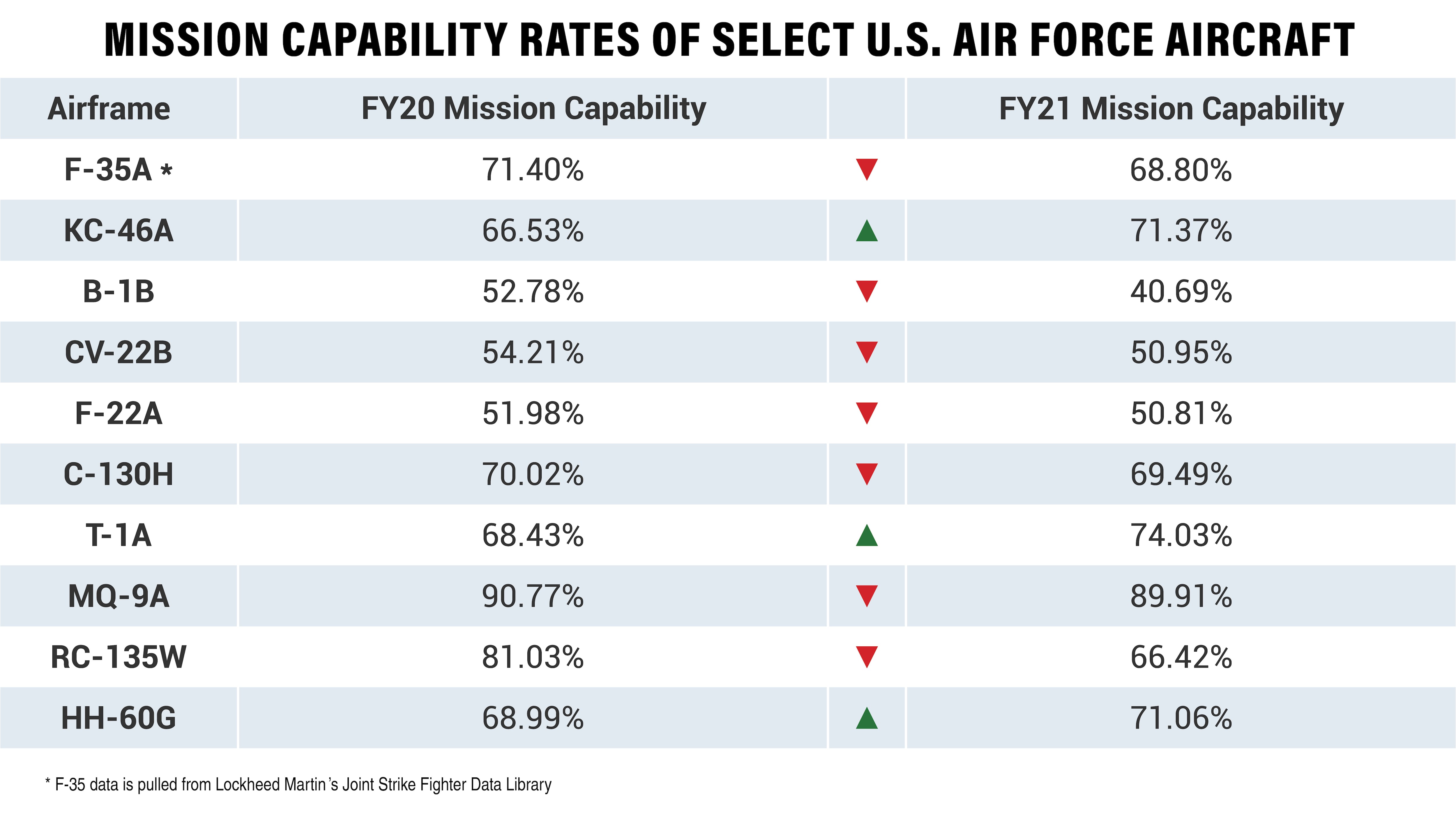

Twenty-nine of about three dozen Air Force fleets — from the C-130H Hercules transport planes to the E-3 target-tracking jets — saw their mission-capable rates fall last year. Another eight logged positive change; one had none at all.

Seven airframes had fewer than 60% of their aircraft ready to go at any given moment, with the B-1B Lancer bombers, F-22A Raptor fighter jets and CV-22B Osprey special operation airlifters at the bottom of the list.

In 2020, 41% of B-1s were in a condition to respond when called upon — the lowest mission-capable rate in the Air Force, thanks to a slew of engine problems that took them out of commission last year.

Twelve airframes logged mission-capable rates between 60% and 70%, including most of the fighter fleets, and 13 platforms clocked in between 70% and 80%. Six airframes had rates of 80% or higher, led by the MQ-9 Reaper and surveillance drones.

Ninety percent of the remotely piloted Reaper attack drones were mission-ready, the highest rate in the Air Force.

RC-135W Rivet Joints had the worst year with a nearly 15 percentage-point drop in its mission-capable rate; the T-1 Jayhawk trainer had the best year, as the last of 39 planes damaged in a 2016 hailstorm returned to service and spurred an almost 6 percentage-point uptick.

Yet, a pattern of two steps forward, one step back has some experts wondering if and when the Air Force will get a handle on its readiness issues, should a longer-term conflict arise — such as, say, a Russian invasion of Ukraine.

How did the Air Force get here?

Several factors have brought the Air Force to this point, said retired Air Force Gen. Hawk Carlisle, president of the National Defense Industrial Association and former head of Air Combat Command.

One of the biggest problems: The Air Force has old iron.

The service’s aircraft now average 29 years old; about half the inventory dates back to the 1980s or earlier. Some planes — like the B-52 Stratofortress, T-38 Talon and KC-135 Stratotanker — have hit their fifth or sixth decade of service. Attempts to replace geriatric fleets with new technology have been slow moving.

When planes get old, Carlisle said, they inevitably need more maintenance — whether on a day-to-day basis or as part of more intensive overhauls that extend an aircraft’s life span but take up more time in depots.

Service-life extension work has become a costly issue for command-and-control as well as intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance planes, the oldest of which date back to the early 1960s. Those airframes perform highly specialized missions, like intercepting communications signals. And with fleets of a few dozen jets at most, going down for maintenance can put the Air Force in a bind.

That calculation could get more challenging as the service prepares to retire some of those assets, like the E-8C Joint Surveillance Target Attack Radar System, which is used to track ground targets from above. Four of 16 JSTARS are headed for the Boneyard this year after long-running pushback from the plane’s supporters on Capitol Hill. Their destination in Arizona is where the Air Force stores thousands of retired military planes, keeping aircraft safe so that parts can be harvested.

Offices across the Air Force will work together to limit the harm that downsizing an already small fleet could do to aircraft availability and institutional knowledge, said Air Combat Command spokesperson Capt. Lauren Gao.

The Air Force hopes to lessen the financial load of keeping the creakiest planes aloft, but perennially struggles to win congressional approval to retire outdated airframes. Lawmakers’ usual resistance thawed somewhat with the FY22 National Defense Authorization Act, which granted most of the Air Force’s requests to downsize certain fleets, but congressional appropriators still need to sign off on the plan.

Last year, the Air Force retired 17 of its most battered B-1Bs so mechanics can concentrate on keeping the remaining 45 Lancers flying. That drawdown, plus an emergency pause in operations to replace potentially faulty fuel tank components, has made more than half of the bombers combat-capable again.

About four in 10 B-1s are available for use, meeting the bar set by Air Force Global Strike Command, said spokesperson Jennifer Greene.

“The fleet has continued to improve in mission capability since that effort and post-divestiture,” she said. “By divesting the most structurally challenged aircraft, the Air Force avoided more than $630 [million] in expensive repairs.”

Getting the congressional go-ahead to ditch certain planes has led the service to consider how it can shuffle airmen to support older fleets on the way out and newer planes that are arriving. In the B-1′s case, the Air Force said it was able to shrink the Lancer fleet without deactivating any squadrons. Instead, it divided existing bombers among B-1 bases to maintain a robust workforce at each in preparation for the plane’s successor, the stealthy B-21 Raider.

While it remains to be seen if the Air Force will reap the wide-ranging benefits of divestment it’s promised, Hartle said the ripple effects are starting.

“The first impact that we’re seeing … is really a lot about the maintenance manpower, as we align some of that [workforce] … to those weapon systems that we are retiring, and then moving [the jobs] … to the new weapon systems that we have or some of those other weapon systems that will be part of our future,” he said.

The service is also on track to sunset nearly three dozen KC-10 and KC-135 tankers in the next two years and upgrade the EC-130H Compass Call with a newer jet. Recent budgets tried to retire or end production of several other airframes, including the F-15 Eagle, F-16 Fighting Falcon, A-10 Thunderbolt II, MQ-9 Reaper, U-2 Dragon Lady, RQ-4 Global Hawk and C-130H Hercules.

Budget problems, such as repeated continuing resolutions, haven’t helped matters, Carlisle said. The stopgap funding measures block federal agencies from spending more than they received in the previous fiscal year.

The current CR that expires Feb. 18, for example, has meant there’s less money to go around to fix both an earlier model of the RQ-4 reconnaissance drone — which Congress wouldn’t let the Air Force retire — and a newer version that is accumulating wear and tear.

That fleet saw a nearly 10-point drop in its mission-capability rate over the past two years.

“We are still operating with identical budget restrictions that contributed to the MC-rate drop, and had to utilize some funding allocated to Block 40 aircraft in order to maintain Block 30 aircraft,” Gao said. “Retiring the Block 30 RQ-4s, however, will allow ACC to fully allocate all of the Block 40′s funding to greatly improve the overall health of the RQ-4 Block 40 fleet.”

Making maintenance headway

Air Force officials tout several steps they’ve recently taken to boost readiness, from introducing virtual reality and 3D printing in the depots to relying on artificial intelligence for more insight. Perhaps no aspect has garnered as much attention as the need to shore up maintenance, whether by getting fixes in place faster, repairing parts before they fail or trying new training approaches.

One initiative is giving bases the resources to handle repairs they couldn’t previously do. For example, B-2 Spirit bombers needed to visit the major maintenance depot in Oklahoma when their hydraulic systems needed work because the B-2 hubs at Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana, and Whiteman Air Force Base, Missouri, weren’t able to fix it locally. Hydraulic components give the stealth aircraft the lift it needs to glide through the sky.

Barksdale prepared to take on that responsibility in the past year, and its personnel fixed nine hydraulic actuators on site instead of rerouting bombers 300 miles away to Oklahoma. It avoided spending $2.7 million in unnecessary purchases as well, Hartle said.

The “repair node integration” effort has cut average repair times from about 41 days to 13 days so far, Hartle added.

“We’re at 3,000 different parts across the … platforms and looking at trying to repair as much as we can through that effort,” he said, estimating cost savings of over $100 million. “We would like to get to about 30,000 parts.”

Another project is adapting routine upkeep to better account for an aircraft’s mission needs.

The Air Force’s largest plane undergoes a thorough 60-day inspection, known as a home station check, every two years. Active duty C-5 units redesigned the inspection around airlift operations and training requirements, freeing up time for nearly 30 more sorties per year for the jets at Travis AFB, California, and an extra 15 flying days for the team at Dover AFB, Delaware, Hartle said.

Officials want to expand the effort to include the KC-46 Pegasus tanker, the B-1 and B-52 bombers, and the forthcoming B-21.

A third effort focuses on working out the kinks that are slowing down an aircraft’s turnaround time. About two dozen projects have hammered out solutions on platforms from the E-3 Airborne Warning and Control System plane to the F-35A Lightning II.

One iteration with the KC-135s cut the number of aircraft undergoing maintenance by 70% and freed up the equivalent of 1,500 flying days, Hartle said. Another with the E-3 boosted its sortie effectiveness by 73% and aircrew training by 81%.

In the long run, the Air Force wants to have contractor liaisons on call to work through those constraints, which can take up to six months. “It’s just a matter of the capacity,” Hartle said.

Pulling out of America’s nearly 20-year war in Afghanistan last year has been a boon to some airframes, too. Now that Air Force Special Operations Command’s MC-130Hs are no longer deployed in the harsh environments of Southwest Asia, it’s easier for maintainers to conduct repairs and stock spare parts at home, according to AFSOC weapons systems chief Lt. Col. Michael Fields.

It’ll take more work to turn around AFSOC’s CV-22 Osprey, however, after its mission-capable rate dropped from about 54% to 51%. Excessive vibrations caused by its unique tilt-rotor design have taken a toll on the airframe, landing it in the shop to address chafing wires and other problems more often, Fields said.

Bell Textron and Boeing are working on improvements to the Osprey’s massive nacelles, the wind turbines that propel it in multiple directions, and they are installing new wiring to get them back into service, he said.

Taking a BLADE to the problem

Artificial intelligence and predictive analytics have taken center stage in experiments to keep spare parts in stock. Existing shortages are exacerbated by pandemic-era supply chain snarls, and there are more complications among decades-old aircraft for which parts are no longer manufactured at all.

That’s been a particularly pressing problem at Air Mobility Command, which is grappling with the exorbitant costs of refurbishing planes dating back to the 1950s. Often, an original manufacturer has closed and the military needs to find another to make components — or 3D print its own.

Each plane has a different set of hard-to-find parts, and they include everything from engine components to pumps and actuators, said Lt. Col. Tiffany Feet, chief of mobility aircraft in the command’s logistics, engineering and force protection division. “There are thousands of parts on these planes, and quite a few of them can bring the plane out of operation,” she said.

Still, she downplayed the related decline in readiness rates, calling it “nominal.”

Supply chain woes made worse by COVID-19′s impact on the industrial base were partly responsible for mission-capable rate drops among the F-15, F-16, F-22 and F-35 fighters, plus the T-6 and T-38 trainer aircraft.

The coronavirus similarly cramped progress toward overhauling T-38 engines and stockpiling spares for the T-6.

In his office’s annual report in January, the Pentagon’s chief weapons tester said F-35 availability rates plateaued in 2021 and started slumping toward the end of the year. The year had started off strong as more new F-35s were delivered and efforts to increase spare parts availability yielded success, the report by the Director, Operational Test & Evaluation Office said.

But after June 2021, spare parts started to dry up, dealing a blow to F-35 readiness, the report said. Most notably, a serious shortage of fully functional F135 engines — felt most acutely in the Air Force’s F-35A fleet — and a lack of depot capacity worsened the fighter’s availability.

COVID-19 drove home the lesson that the Air Force needs to better predict its future, Hartle said. That led to the creation of a database known as “BLADE,” which is run on a Pentagon-wide artificial intelligence platform.

BLADE is compiling information on how parts move through the supply chain, if they’ll arrive before a jet is in dire need and how the Air Force should invest in those logistics, Hartle said. It’s meant to alleviate future binds that industry backlogs may create for national defense.

BLADE goes hand in hand with conditions-based maintenance, or CBM+, an initiative that began in 2019 and has since spread to more than a dozen types of aircraft. The project was inspired by the commercial airline industry’s practice of proactively using sensors and algorithms to forecast when plane parts are about to fail — rather than reactively replacing broken parts.

“We don’t want those unexpected breaks,” Feet said. “We want to build that reliability into our flying operations.”

Bringing it all together

The Air Force plans to pull the data from its myriad initiatives into a new bird’s-eye view of fleet availability, dubbed the “ready aircraft metric.”

“We are working to provide our maintainers and our logisticians a tool that, based on a certain period of time [and] the scheduled maintenance tasks that are going to be required over that time, they can actually predict their fleet readiness,” Hartle said.

It presents a more forward-looking approach to military aviation compared to mission-capable rates, which airmen criticize as a lagging metric that rewards keeping planes on the ground instead of giving them the chance to degrade in the air.

The Air Staff at Air Force headquarters is partnering with nearly all of the service’s major commands on a pilot program to decide which data is most helpful and how to present it. If it goes well, the service plans to scale the idea across the entire inventory over the next few years.

It “will give our operators, our maintainers, our planners in how we present forces … key information as we look forward,” Hartle said.

He also expects the situation to improve as green maintainers gain experience in their craft and fill jobs where units are lacking. Renewed interest in civilian contractors can help.

In October 2020, the Air Force’s training enterprise opened a new center to teach civilians how to sustain the service’s three main flight school planes. Nearly 150 people graduated from the Texas-based center in its first year and will take over open positions as workers retire.

Views from the Hill

If the Air Force is going to fix this problem, it can’t stop at dumping old airframes, said Todd Harrison of the Center for Strategic and International Studies. He argues the military is overdue for a radical reimagining of what its combatant commanders — particularly U.S. Central Command — can ask of the Air Force.

The Pentagon’s Global Posture Review offered an opportunity to shrink commanders’ demands, but punted on CENTCOM — “arguably the worst offender in terms of continuing to ask for [air] forces,” Harrison said. “It seems like no one has told CENTCOM that they’re not the priority anymore.”

Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle will take another crack at the issue as well.

A spokesperson for Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., who chairs the Senate Armed Services Committee’s readiness and management support subcommittee, said the lawmaker plans to look through readiness reports from the first three months of FY22 to see where the most pressing issues lie.

Kaine is also “focused on passing a full-year defense appropriations bill to provide more certainty for readiness for the Air Force and all branches of the military,” Ilse Zuniga added in the Jan. 26 email to Air Force Times.

Congressional hearings may uncover new details about how the Air Force is progressing toward a more reliable, four-phase cycle of training, maintenance and deployment; whether funneling more than $2 billion in the past four years to update its maintenance depots has helped; and if it can successfully adopt the analysis and networking technologies that have powered commercial industry for years, among other issues.

Previous defense policy laws have directed the Pentagon to draw up infrastructure and depot improvement blueprints. But proposing a 25-year plan is not the answer, Rep. John Garamendi, D-Calif., head of the House Armed Services Committee’s readiness subpanel, said in October.

“This committee perceives the problem, and we damn well intend to solve it, so get ready,” he said.

Rachel Cohen is the editor of Air Force Times. She joined the publication as its senior reporter in March 2021. Her work has appeared in the Washington Post, the Frederick News-Post (Md.), Air and Space Forces Magazine, Inside Defense, Inside Health Policy and elsewhere.

Stephen Losey is the air warfare reporter for Defense News. He previously covered leadership and personnel issues at Air Force Times, and the Pentagon, special operations and air warfare at Military.com. He has traveled to the Middle East to cover U.S. Air Force operations.