ABOARD AN E-4B NIGHTWATCH JET OVER THE GREAT PLAINS — Sixty years after the Cuban Missile Crisis brought the world to the brink of nuclear war, one of the U.S. military’s most unique airplanes is still standing guard in case of catastrophe.

The E-4B National Airborne Operations Center — also known as “Nightwatch” — is a flying office for the secretary of defense that uses 42 different communications systems that enable it to connect to anyone in the world.

It’s also built to withstand a nuclear attack and keep the federal government running from the skies, earning it another eye-popping nickname: “the Doomsday plane.”

But in a new era of geopolitics and technology, does America still need the Nightwatch?

What is the ‘Doomsday plane’?

Air Force Times on April 26 got a rare opportunity to board “GORDO14,” one of America’s four E-4Bs flown by the 595th Command and Control Group at Offutt Air Force Base, Nebraska, for a two-hour spin over America’s heartland.

On its best day, the jet offers 5,000 square feet of mobile office space, complete with a secure conference room, media briefing room and a few cots. On its worst, it’s a hub for the president and other federal officials to orchestrate war while remaining airborne for three days at a time.

Its pre-takeoff safety briefing echoes that of any commercial airliner, but this is not your average Boeing 747. Specialized masks hang in the cockpit to keep pilots from being blinded by nuclear blasts, and its few windows are covered in a mesh that protects against electromagnetic shockwaves from those explosions.

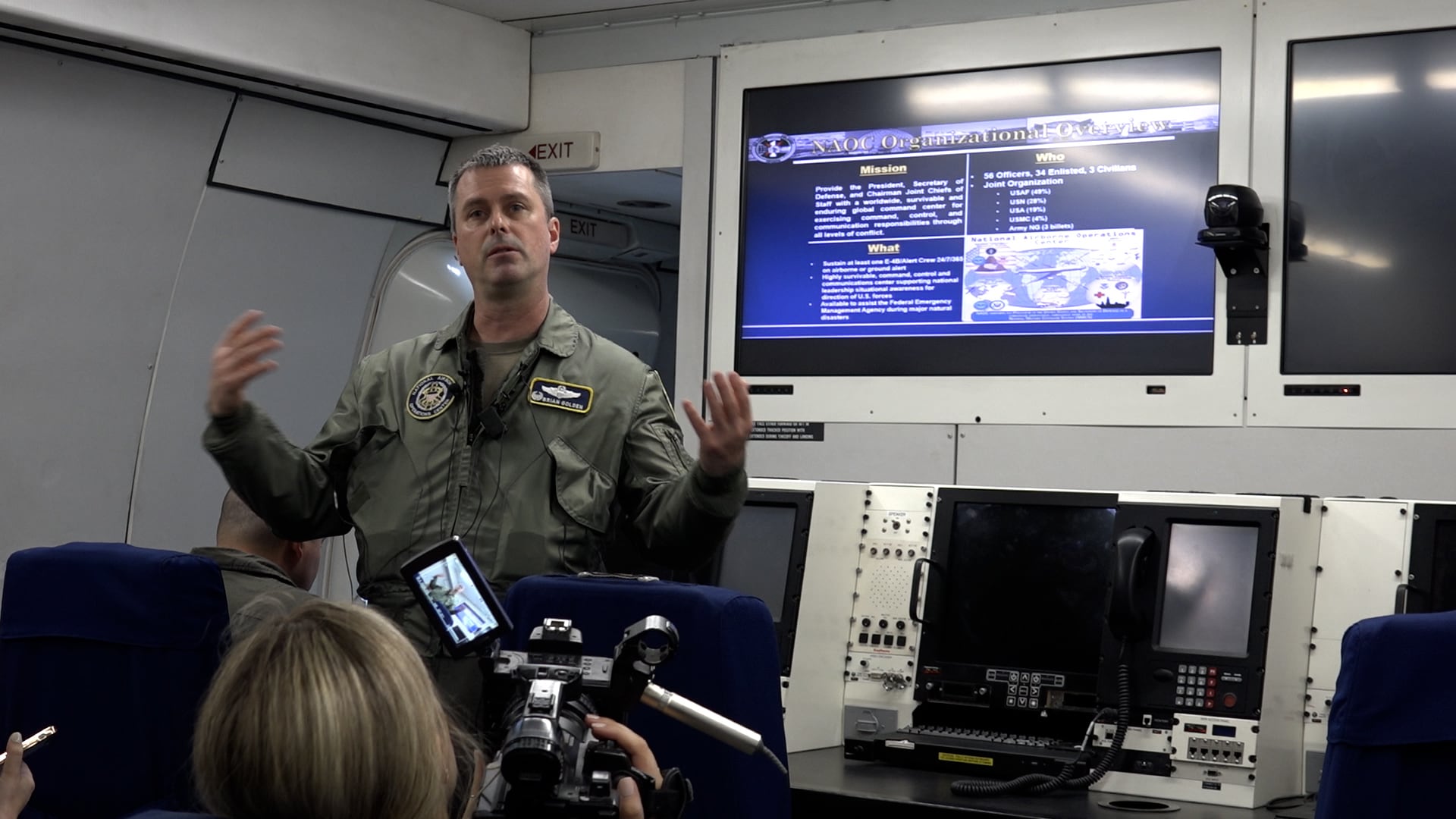

The 42-year-old fuselage bears witness to large and small moments in presidential history. On Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin’s first Nightwatch flight, he joined a video conference in which President Joe Biden decided to withdraw American troops from Afghanistan, 595th Command and Control Group boss Col. Brian Golden told reporters.

Presidents Carter and Ronald Reagan are the only two presidents who have publicly flown on the E-4B.

Periodic upgrades and 30-day stretches of heavy maintenance take jets out of an already limited rotation, so Secretary Austin currently only uses the E-4B for overseas trips.

It can fit a crew of 65 troops, from pilots with several years of experience under their belts to communications system operators fresh out of technical school. A flight engineer, navigator, flight attendants and security forces are part of the aircrew as well.

For one of the oldest platforms in the Air Force’s inventory, it carries one of the service’s most advanced and diverse suites of audiovisual and data transmission technology.

At the ready

One E-4B is always on alert, meaning its rows of boxy communications systems are on and one of the plane’s four engines could be running in case the crew needs to jump in at a moment’s notice.

Together, the comms specialists decide which satellites, radars and antennas create the best route to talk to the outside world.

“This jet does not shut down — 24/7, 365, there’s folks back there making sure that those 42 disparate communication systems are connected when they need to be connected, and they’re constantly maintaining those,” said Lt. Col. Mike Shirley, the 1st Airborne Command Control Squadron commander. “They’re also receiving notifications, receiving messages and providing that information to the battle staff.”

Depending on the needs of the VIPs and joint battle staffers on board, the jets can reach any cell phone or landline number. They can pull in radio and television signals, read text messages and broadcast their own video. And they can communicate with other military platforms around the world, including units on the ground or undersea.

The Nightwatch can also serve as a utility player during natural disasters where phone lines and other forms of contact have been wiped out. The jet can ensure governors can reach the federal entities they need or bolster connections for first responders until regular service is restored.

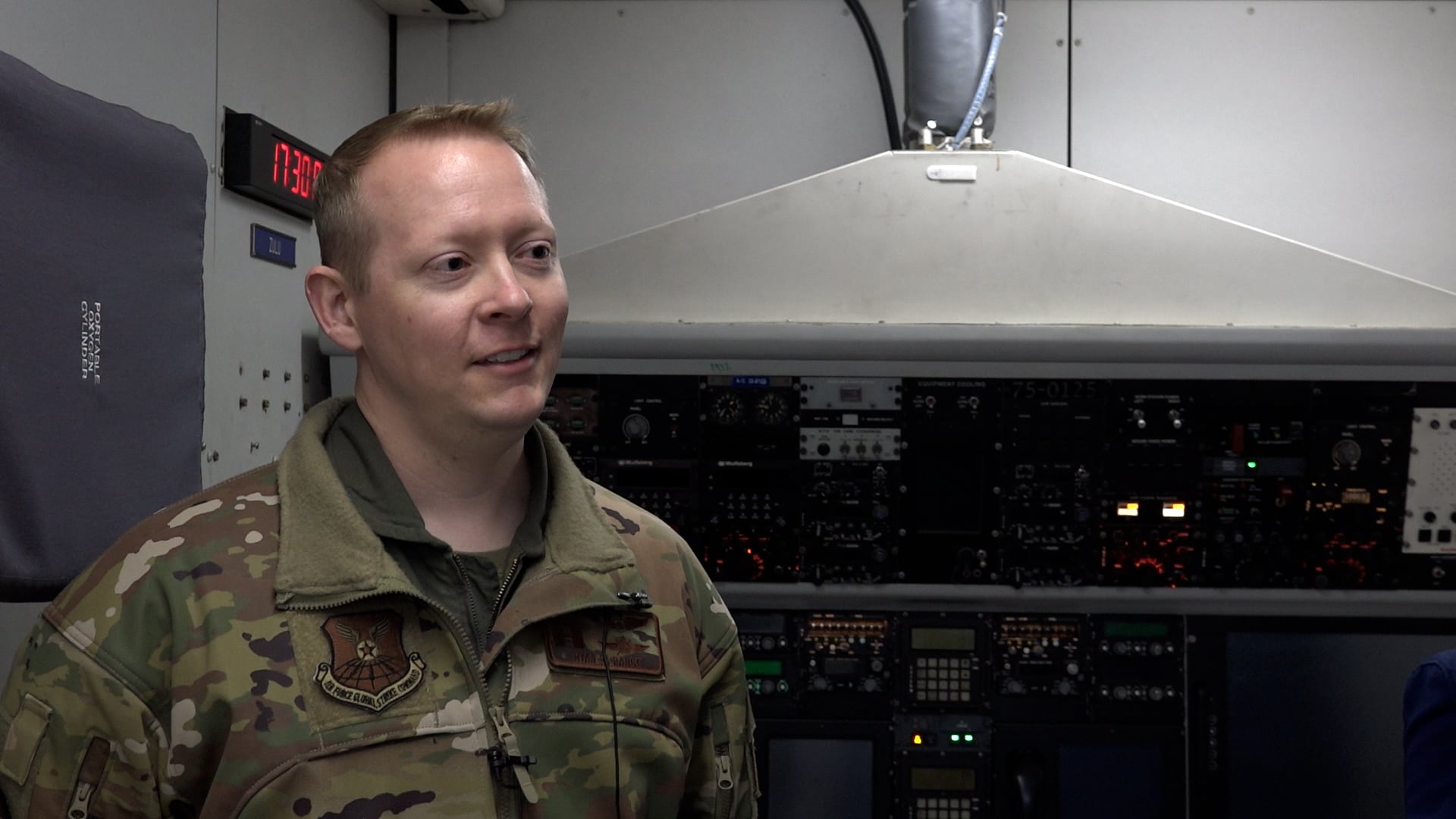

“We have so many different things that we can do, we’re able to fill a gap whenever one arises,” said communications control officer Capt. Ryan La Rance, who manages the airmen at the back of the plane. “Our military is very powerful, very lethal, but it doesn’t happen without communication.”

An evolving mission

The Nightwatch hasn’t always been the Swiss Army knife of military comms.

Its mission was initially geared toward directing America’s nuclear assets during the Cold War, plus a few other means of connecting national leaders, Golden said. That began to change with the advent of the Internet and satellite communications.

“Around 9/11, we started having more and more requirements put on us because they realized that this platform was very survivable, it was always up and running and had a lot of room and had a lot of capability with the human capital on board,” he said.

Though its role in a nuclear catastrophe garners the most attention, the fleet can come in handy in a conventional attack on the homeland, a debilitating power grid failure or a devastating natural disaster.

“The plane provides a level of physical security and resilience, and the national command authority, that I think is still entirely relevant and appropriate,” said Todd Harrison, a military aviation expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Military historian Robert Hopkins noted in May 2021 that in the immediate aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks, President George W. Bush opted to stay on a VC-25A — designated “Air Force One” when the commander in chief is on board — instead of jumping onto an available E-4B during a stop at Offutt.

“Another E-4B was caught on camera launching out of [Joint Base Andrews, Maryland] right after the attacks, resulting in a rash of conspiracy theories, and yet another one was shortly airborne over the Midwest,” Hopkins said.

In an extreme crisis, he added, it appears that the president and their advisers would instead take flight on a Doomsday plane.

Imagine if another country started firing cruise missiles into D.C., Harrison said.

“That could persist for days. … You absolutely are going to need to get your command authority out of the region,” he said.

Golden doesn’t foresee any major additions to the jet’s capabilities, unless some game-changing technology arises that the military needs to address. As the Air Force’s new B-21 Raider stealth bomber, Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missiles, air-launched cruise missiles and other nuclear assets come online, E-4B crews will learn how to connect with those systems as well.

The Nightwatch is “already poised” to handle more advanced hypersonic weapons that can change direction in flight as long as the crew is warned of a launch, he said.

The colonel also said he’s not worried about the possibility of China or Russia interfering with the E-4B’s comms suite. An adversary could degrade or try to shut down a few systems on the airplane, but the crew would likely still be able to rely on a few dozen other tools for connectivity.

“We have to stay ahead of them,” he added.

The national command fleet has garnered more interest lately as America watches the Russo-Ukrainian war unfold, concerned that Moscow may introduce nuclear weapons into the conflict. But Golden said his group hasn’t changed its usual daily routine.

“We’re monitoring situations, we’re making sure we’re up and running all the time,” Golden said. “If there is ever a threat to the continental United States, that’s when we would be a little more concerned.”

Joining the crew

The Doomsday fleet is run by a joint battle staff of 90 service members, about half of whom are airmen; 244 ops crew members, like flight engineers, flight attendants and comms operators; and 277 maintainers. The jet can fly with up to 112 people aboard.

Senior Airman Dallas Jump said he put Offutt at the top of his base wish list when he graduated from basic military training. He snagged it and was assigned to his first job as a Nightwatch communications systems operator.

“I never thought I would be doing anything like this in my life … getting paid to fly and talk on radios,” he said.

Multiple airmen spoke about the fulfillment of directly affecting national security on a daily basis, and avoiding a typical 9-to-5 job.

“Sometimes you get four-star generals on the phone, on these conferences, making decisions,” said La Rance, the communications control officer. “I have an impact on who they’re talking to and how they’re hearing it.”

Right now, pilots go to Miami, Florida, for 30 days of training in a Boeing 747-200 simulator also used by E-4B flight attendants and Air Force One crews. Aviators then show their proficiency at air refueling, nighttime operations and other typical tasks across several flights before the final qualification ride.

“Our pilots are going to be able to practice something that is incredibly challenging, which is air refueling this aircraft,” Shirley said. “That’s a huge, huge capability for us.”

Communications operators can spend up to nine months in training, depending on the complexity of their job.

For the first time in the program’s history, airmen could soon have an E-4B simulator — scheduled to open by June 1 — that is expected to handle up to 80% of the unit’s training. That will free up a jet for regular operations instead of being used for practice, though how that will impact fleet readiness is still unclear.

Despite the draw of a unique mission, Golden said retaining experienced communications specialists and maintainers is a perennial concern. The Nightwatch program also competes with the Space Force for satellite communications operators.

The constant schedule of two weeks on alert and four weeks in an office job can be tiring, airmen said. They’d also like more food trucks in Nebraska. But the job on the jet is often worth it.

“Normally I’m making sure the general gets his email,” La Rance said. “This is one of the few jobs in the Air Force where a comm officer like me gets to fly in the airplane. I’m going to live that up to the fullest extent possible.”

Looking ahead

Now, the Nightwatch carries everything it needs for any situation it might face. But can it last?

Golden said the Air Force should know within the next year or two whether it will pursue a more efficient National Airborne Operations Center from the start, or whether it will design new equipment for the current jets, which could eventually be moved to another airframe.

Experts who spoke with Air Force Times suggested the military combine the E-4B and its close counterpart, the Navy’s E-6B Mercury, onto a single airframe for more flexibility if things go south.

While the E-4B is a flying command center for civilian leadership and can talk to nuclear bombers, missiles and submarines, only the E-6B can order those weapons to launch.

“Why wouldn’t you want to add that to your E-4? It makes perfect sense,” Harrison said of nuclear launch capabilities. “If you’ve got a key element of your command authority on the plane, who would be giving the orders, then why not have the physical means of distributing those orders on that plane?”

The services had explored the idea of combining the E-4B, E-6B and potentially the smaller C-32 executive transport jets into a single fleet. It appears that plan has fizzled out.

Officials argue the three wouldn’t work together, and budget documents no longer describe the “Survivable Airborne Operations Center,” or SAOC, as an airframe to consolidate the E-4B and E-6B.

“Totally different mission sets, so they have totally different requirements,” Golden said, adding that combining them wouldn’t leave room for passengers. He also believes that creating a single national command plane would cut down the Pentagon’s options for keeping in contact.

Harrison contends that technology has shrunk enough over the past few decades that the Pentagon could stuff more capability into a smaller airframe.

The Air Force plans to spend at least $3.4 billion to research a new Doomsday plane, though the price tag is still in flux. A development contract for the fleet’s replacement is due out in mid-2023, about a decade before the airframe’s estimated lifespan of 115,000 flight hours expires.

The War Zone recently reported that the Navy is buying three extended-length C-130J-30s from Lockheed Martin for testing as its new E-6B “Take Charge and Move Out” (TACAMO) plane, while the Air Force is still considering its options for a new Nightwatch.

The E-6B will be configured to send ballistic missile launch messages to nuclear-armed submarines, but not to air-launched or underground nukes as it does now — leading to speculation that the Air Force could take over that piece of the mission instead.

As military competition with China and Russia takes center stage, Kristensen believes the Air Force will end up replacing the Nightwatch with a similarly iconic command-and-control jet.

“There’s a fair amount of symbolism in it,” he said.

After the flood

In March 2019, a flood devastated Offutt Air Force Base. While its crumbling runway is renovated, some E-4B crew members must commute about an hour from Omaha to Lincoln Airport, their temporary airfield until the 18-month project is done this fall. Others live in Lincoln for two weeks at a time for more stability.

RELATED

Golden said his predecessor had to work out of 12 different offices as Offutt scrambled to relocate people after the flood. But what’s more important than a spot for leadership has been the impact on flyers and maintainers, who were displaced from their hangar, spread across multiple offices on base and now must work from two airfields.

Airmen will have to wait three years or longer for brand-new facilities at Offutt where they can work, spend time with family and sleep while awaiting a call to action.

The 595th’s offices and alert facility were irreparably damaged in the freak flood that engulfed about one-third of Offutt; the base is using it as an opportunity to overhaul its campus and bring parts of the unit under the same roof.

Despite those setbacks, airmen on the E-4B said they still find meaning in the mission and love their ability to fly.

“We are proving to the world … ‘Look, [the U.S.] can do our business,’” Golden said.

With the media flight behind them, airmen climbed aboard GORDO14, booted up their classified screens and took off into the clear Nebraska sky — training once again for the day everyone hopes never comes.

Rachel Cohen is the editor of Air Force Times. She joined the publication as its senior reporter in March 2021. Her work has appeared in the Washington Post, the Frederick News-Post (Md.), Air and Space Forces Magazine, Inside Defense, Inside Health Policy and elsewhere.