FORT BRAGG, N.C. — A company of combat engineers gathered on a Fort Bragg memorial field before sunrise one recent morning to take a fitness test, the same way many units in the Army do every day.

But those units don’t have to navigate 225-pound tires, 240-pound mannequins, 40-pound sandbags and 7-foot barriers to complete their physical fitness tests.

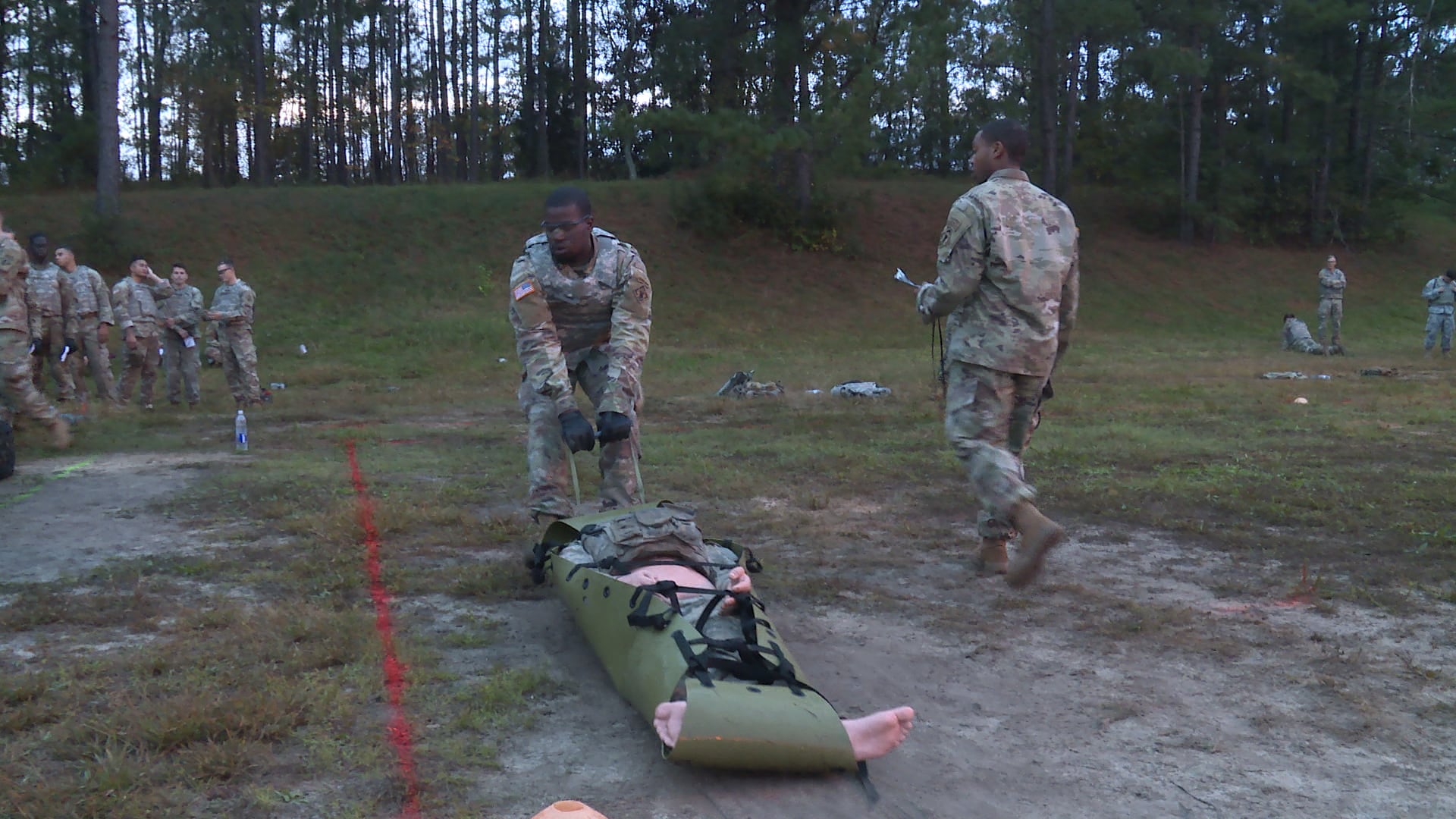

On Nov. 2, 40 soldiers from 264th Engineer Company completed a pilot run of the Soldier Readiness Test, a new three-phase, seven-event test that Army Forces Command is developing to measure unit combat readiness.

“I feel like a warrior,” Spc. Anita Drake, one of the Army’s first female 12B combat engineers, told Army Times after finishing the test.

The soldiers’ brigade commander made sure his unit was included in FORSCOM’s ongoing trials of the Soldier Readiness Test.

“I heard through the grapevine that this pilot program was coming up,” Col. Marc Hoffmeister, commander of the 20th Engineer Brigade, told Army Times in an Oct. 27 phone interview.

“I fought to have our brigade included in the program, because I realize where the Army’s going in terms of shifting our focus toward a culture of fitness that I truly believe in.”

Hoffmeister’s brigade is one of four brigades to pilot the Soldier Readiness Test.

“Even before we had done this, we were actually in the process of implementing what we call the Castle Total Fitness Program in our brigade,” Hoffmeister said.

The SRT falls right in line with the kind of functional fitness he wanted to bring in to the brigade, he added.

Holistic fitness

The SRT is part of a larger Army push toward a more holistic way of looking at fitness.

“A lot of the things that they have been doing physically have been very good, but doing pushups and sit-ups might not be the best way to get you ready for the terrain of Afghanistan,” Michael Bugielski, the 20th Engineer Brigade’s certified strength and conditioning coach, told Army Times.

RELATED

The age-old old trifecta of run, pushups and sit-ups — as tested in the Army Physical Fitness Test — is on its way out as a measurement of combat readiness.

It only measures aerobic endurance and one type of muscular endurance, experts say.

Meanwhile, factors like agility, explosive power and strength give a more complete picture of physical fitness.

The Army also wants to reduce overuse injuries among soldiers, so it is working to create a PT program that looks more like the physically demanding tasks related to soldiers’ jobs.

This way, soldiers are strong enough and aware enough of their movements to prevent costly injuries that keep them out of the fight.

FORSCOM has not made any decisions about how the SRT would be graded, but officials told Army Times earlier this year that it would likely be administered for a commander’s awareness, and not as a test of record with possible career repercussions, like the Army Physical Fitness Test.

Dueling tests

The Army Combat Readiness Test, however, is still in development by Army Training and Doctrine Command, and that test, if approved, would be individually graded like the APFT.

That six-event test starts with a two-mile run and then goes into five more activities that measure strength, muscular endurance and explosive power.

Maj. Gen. Malcolm Frost, commander of the Center for Initial Military Training, told Army Times earlier this year that the Army Combat Readiness Test, if approved, could eventually replace the APFT altogether.

The SRT, on the other hand, would be a bonus.

RELATED

Tailor-made

The SRT breaks new ground for Army fitness tests not only because it requires equipment, but because it has no gender or age standards. There also are four variations based on the type of brigade a soldier belongs to.

The 20th Engineer Brigade did the multi-functional brigade version of the test.

Soldiers in 1st Stryker Brigade, 2nd Infantry Division at Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Washington, performed the Stryker brigade version.

And soldiers in 3rd Brigade, 1st Armored Division at Fort Bliss, Texas, and 1st Brigade Combat Team, 10th Mountain Division at Fort Drum, New York, did the armored and infantry brigade versions, respectively.

Each version of the test requires something a bit different, based on the kinds of tasks inherent to each type of brigade.

However, each test includes:

- Flipping a 225-pound tire six times, in a straight line, in 30 seconds.

- An agility test where soldiers shuffled 40 meters in a T shape in 30 seconds.

- Dragging a 240-pound dummy 15 meters.

- Tossing a 40-pound sandbag over a 7-foot barrier 10 times.

- A 1.5-mile run, with four obstacles at the .75-mile mark, to be completed in 18 minutes.

The variations in the test, based on the type of brigade, came between the dummy drag and the sandbag toss.

An armored brigade soldier will have to carry two 45-pound water cans 200 meters.

Infantry brigade soldiers have to carry seven 40-pound sandbags five meters, then stack them.

Stryker soldiers have to do a step-up drill with a 40-pound sandbag, doing 30 repetitions onto a 16-inch platform.

And multi-functional brigade soldiers have to lift 10 40-pound sandbags three feet onto the back of a vehicle, stack them, and stack them on the ground again.

Coupled with the sandbag toss, soldiers have just three minutes to handle the heavy stuff.

Combat gear

The 264th Engineer Company soldiers had to do all of this in their Army Combat Uniforms, including their improved outer tactical vest with ballistic plates.

They were running in boots and wore ballistic eye protection.

The biggest key to completing the test properly is form, said Sgt. Matthew Greene, one of the graders that morning.

“Proper form helps stop soldiers from getting hurt ... ensuring that they get a proper squat, especially during the tire flip and when lifting the 40-pound sandbags,” he said. “That ensures that they’re not putting too much pressure into their lower back.”

Soldiers were given three warnings about improper form before being disqualified.

Simulating combat

Each event was carefully thought out for its approximation of what happens in a combat situation, Col. Mike Kirkpatrick, FORSCOM’s director of leader development, told Army Times.

The tire flip measures a soldier’s ability to generate and apply force. The agility test measures whether a soldier can move quickly over, under, around and through obstacles.

The casualty drag quite literally simulates something that happens in combat, but it also approximates the lifting, carrying and dragging of heavy loads.

The 240-pound load represents an average, 198-pound soldier in full gear.

The water can carry measures muscular endurance, balance and coordination.

“For example, conducting hasty water or fuel resupply operations between armored vehicles in tactical assemble areas,” Kirkpatrick said. “This event relates to working for extended periods of time.”

Carrying and stacking sandbags approximates the same skills for infantrybrigades.

“For example, constructing dismounted fighting positions with sandbag protection,” he said.

For the multi-functional brigades, stacking sandbags simulates loading transport vehicles to supply forward positions.

And in the Stryker, it’s necessary to step up into the combat vehicle to load it up — hence the step-up event.

Training for readiness

For the 264th Engineer Company, preparations for the pilot began three months ago.

Each piloting brigade selected three battalions to be gold, silver or bronze in the preparation phase.

This company was in the gold battalion, said Capt. Audrey Atwell, the 264th’s commanding officer.

That meant she had the full suite of support and equipment to train her troops.

That included a Military Medical Augmentation Team, with an occupational therapist, physical therapist and registered dietitian.

They also had a certified strength and conditioning coach and two nationally certified fitness trainers.

That was music to Hoffmeister’s ears, as the brigade commander and fitness enthusiast had felt stymied by a lack of equipment and support.

“I knew it would provide resources that we do not have available to us,” he said. “Because of that lack of resources, it’s very difficult to continue to grow the culture of fitness I was after.”

But the kicker, Atwell said, was a Beaverfit tactical gym box full of functional fitness equipment, including pull-up bars, a squat rack, kettle bells, a bench and weights.

“It allows us to rotate the platoons through, one at a time, multiple times a week,” she said. “It’s a gym in a box, basically.”

It’s also portable, Atwell added, so they could take it to the field or on deployment and keep the training going.

“I think the squat rack really helped me out, because at first my legs were kind of weak,” Spc. Eduardo Salinas told Army Times. “All three [lifting] events are squatting, so that really helped me out.”

The silver battalions had the Beaverfit boxes, plus the strength and conditioning coach and master fitness trainers, but not the medical team.

And the bronze battalions had to train for the test with what they were able to source on their own, with no additional personnel or help.

The Army will compare the outcomes for each type of battalion as it reviews the pilot results, Atwell said.

For her, the extra support and equipment transformed the company’s physical training program and medical readiness.

“Sometimes it doesn’t work out as well as it should to send soldiers to the gym in the morning during PT hours,” she said.

But the Beaverfit boxes allow the entire company to get some time working out, supervised, in the company area.

With that equipment, soldiers were also able to replicate the motions on the SRT.

“One of the drills is a tire flip. A tire flip is very similar to a squat, but also to a press or a clean,” Bugielski, the certified strength and conditioning coach, told Army Times.

“And so, by incorporating those Olympic lifts into their exercise routine, it’s going to be much more applicable to their everyday MOS and also to this test.”

The medical staff allowed the company to do 100 percent height and weight checks every month, Atwell said, to get on top of physical readiness in general.

“We actually have significantly more soldiers who are either borderline, or in danger of becoming enrolled into the Army Body Fat Composition Program,” she said.

And keeping those kinds of tabs helps leaders tailor fitness programs to each affected soldier and get them back on track.

“This helps me as a leader by identifying who is strong, physically, and who needs a little bit of help, physically,” 1st Lt. Arianne Hendrick, a platoon leader, told Army Times.

Overall, Atwell said, her company’s medical readiness is up between 6 percent and 7 percent.

“For me, in my formation, 6 to 7 percent equals 15 to 20 soldiers who are no longer on profile,” she said.

Hoffmeister’s hope, he said, is that the pilot is a first step to a different way of looking at combat readiness.

“It’s, frankly, not about the test, but it’s how we build our tactical athletes,” he said.

“We don’t train to the test. The test has created a catalyst for change in how we approach fitness.”

RELATED

The Army’s new combat readiness test is part of a holistic push for soldier health and nutrition

‘It sucked’

Of the soldiers who spoke to Army Times after the test, there were mixed responses about whether the sandbag toss or the run was the most brutal.

For Drake, it was the toss, she said, because at just about 5 feet tall, she had a long way to throw the bags. Taller soldiers had an easier time.

“The most intimidating event of this SRT for me, personally, was the run,” Hendrick said. “First of all, it’s at the very end of all the aerobic exercises, and, second of all, you’re doing it in IOTV and boots.”

But, it turned out, she said, that the toss was the toughest part as well.

“As soon as you smoke yourself through that, going into the run, it’s like your legs hit a brick wall,” she said. “But once you get going again, it’s actually not that bad.”

By the end, soldiers were drenched in sweat and winded, many hobbling over to the edges of the field for a smoke break, once they got their breath back.

“I was kind of upset, because my legs couldn’t even move toward the end,” Salinas said. “But I was happy, because it sucked.”

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.