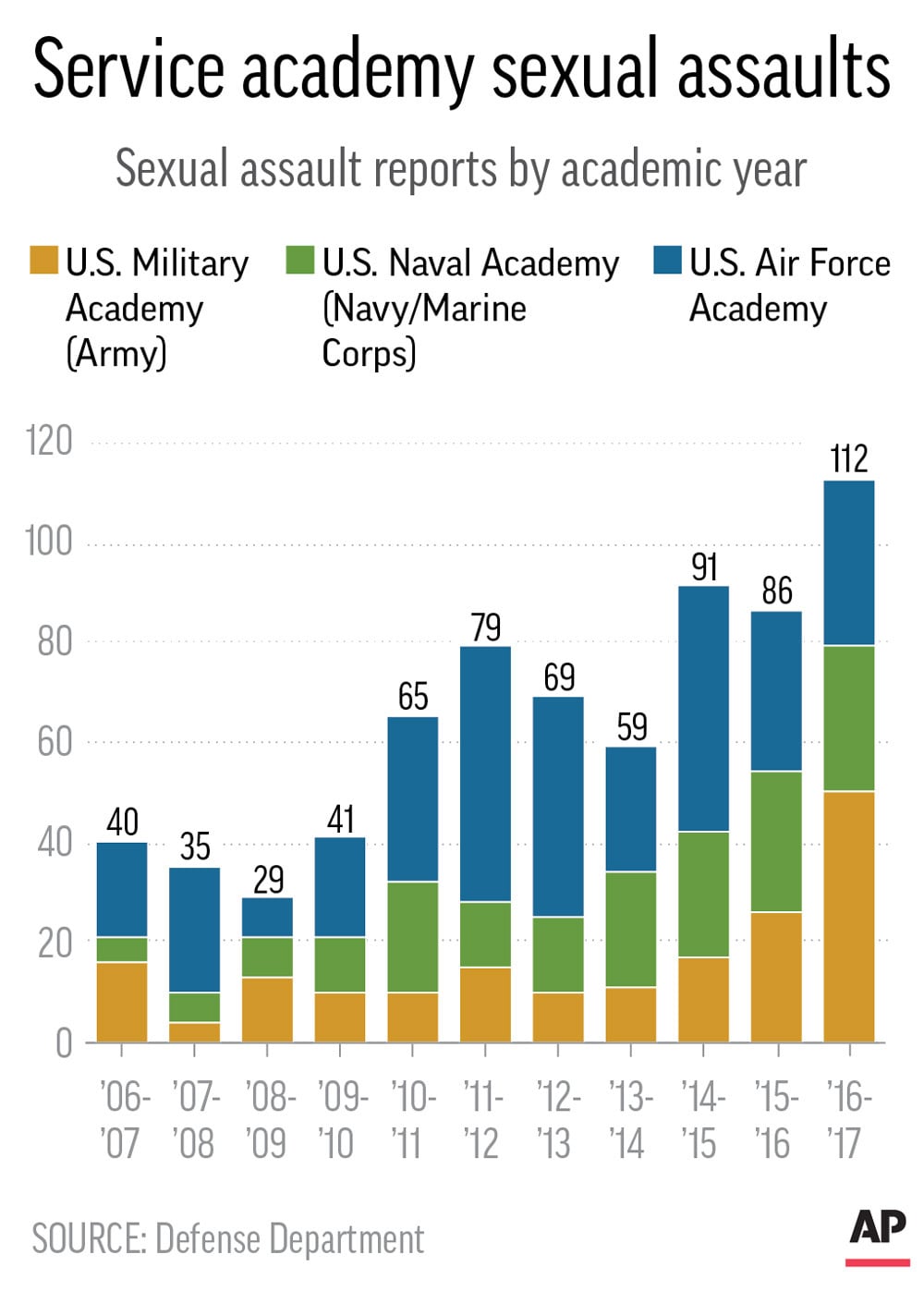

The number of sexual assaults reported at the U.S. Military Academy roughly doubled during the last school year, according to data reviewed by The Associated Press, in the latest example of the armed forces’ persistent struggle to root out such misbehavior.

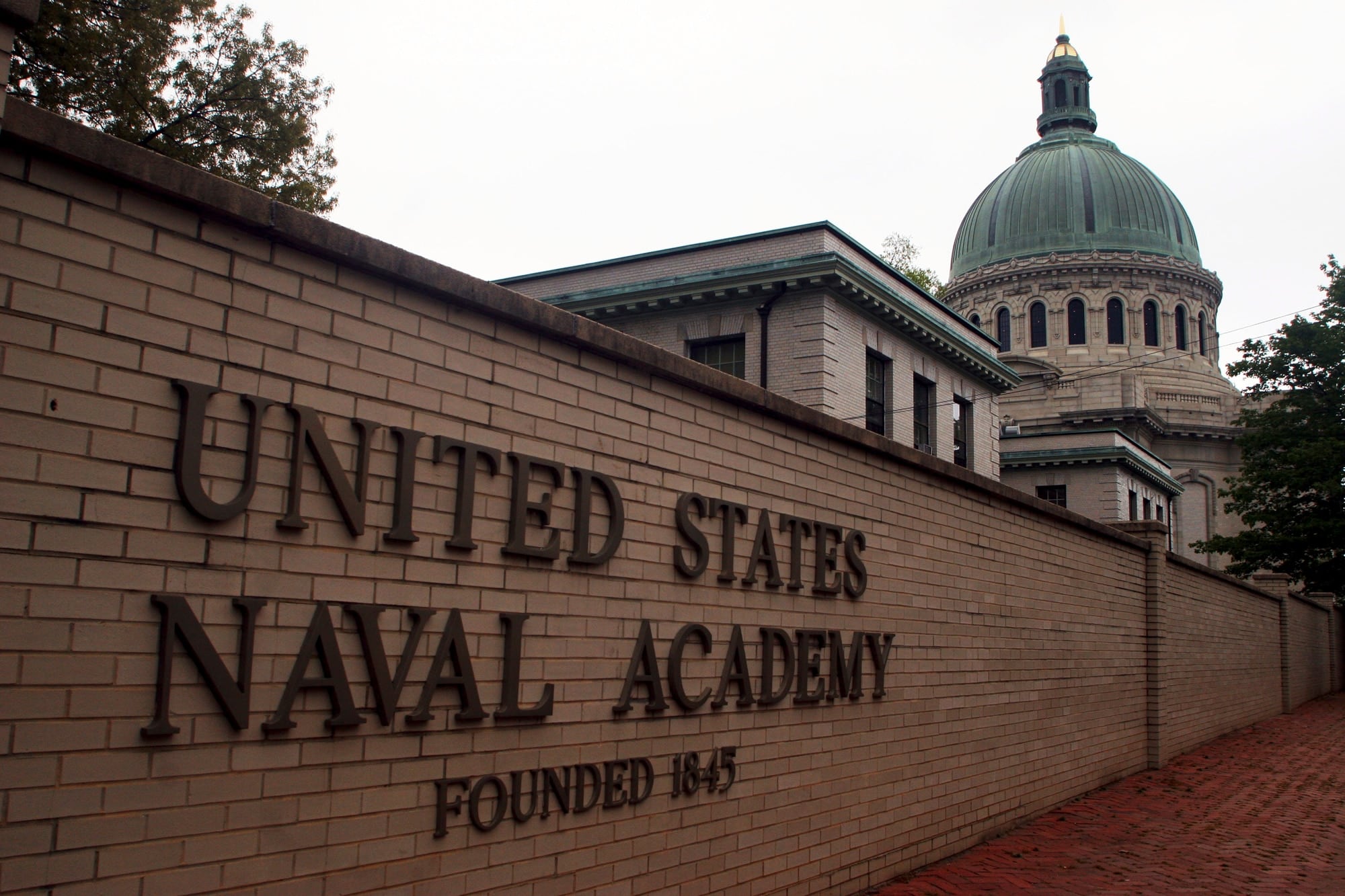

It’s the fourth year in a row that sexual assault reports increased at the school in West Point, New York. There were 50 cases in the school year that ended last summer, compared with 26 made during the 2015-2016 school year. By comparison, the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, and the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colorado, saw only slight increases.

Defense Department and West Point officials said the big jump at the Military Academy resulted from a concerted effort to encourage victims to come forward. But the dramatic and consistent increases may suggest more assaults are happening.

“I’m very encouraged by the reporting,” Lt. Gen. Robert Caslen, superintendent at West Point, told the AP in an interview. “I recognize that people are not going to understand” the desire for increased reporting, he said. But, he added, “I’ve got the steel stomach to take the criticism.”

The annual report on sexual assaults at the three military academies is due out this month. The Naval Academy’s reports increased to 29 last year from 28. The Air Force Academy’s edged up by one, to 33.

About 12,000 students are enrolled across all three institutions. The AP reviewed the data ahead of its public release.

The report highlights persistent problems within the Air Force Academy’s sexual assault prevention office that emerged late last year. Staffing and management issues led to sweeping disciplinary actions, the resignation of the director and an office restructuring.

Those problems could cast doubt on a sharp decline in reported sexual assaults at the Air Force Academy for the 2015-16 school year, considering a widespread loss of confidence in the office. Students may have been reluctant to file reports.

RELATED

There have been worrying trends.

An anonymous survey released last year suggested there were more sexual assaults, unwanted sexual contact and other bad behavior at all three academies. It found 12 percent of women and nearly 2 percent of men said they experienced unwanted sexual contact. The largest increases were at the Army and Navy academies.

In response, West Point leaders took steps to get more victims to come forward. “When we saw that, we did a complete review of our strategy,” Caslen said. “We went after increased reporting.”

Officials moved the sexual assault reporting center to a more accessible area on campus with a private entrance. It had been in a building where students facing discipline had to go.

“I’ve been telling them to do that for years,” said Nate Galbreath, deputy director of the Pentagon’s sexual assault prevention office. “Walking into the building where lots of people who are getting in trouble go, that is a real disincentive for people to come forward and make a report.”

West Point also loosened regulations forcing cadets to publicly report sexual assaults. Now they can seek help anonymously without filing a formal report, which many victims are reluctant to do.

Military leaders have said that an increase in sexual assault reports is good because it shows that students are aware of treatment programs and showing confidence in the system. Officials say they want to see the number of reports more closely mirror the higher levels of bad behavior suggested in their annual anonymous surveys.

The overall goal, however, is more prevention, fewer assaults and effective help for victims.

Brig. Gen. Omar Jones, the Army’s public affairs chief, said this year’s increase resulted from “proactive and deliberate initiatives” to help victims report incidents.

There was an overall decline in reports over the 2015-16 school year at the three academies because Army and Navy increases were offset by a sharp drop at the Air Force Academy. But the Air Force Academy’s subsequent controversies raise questions about whether many victims avoided the office and didn’t file reports.

Last year, the Air Force Academy released a scathing report saying its Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office suffered from infighting, rumors and shoddy record keeping. It recommended firing the director, Teresa Beasley. She resigned.

“Are there people that are out there that weren’t able to make the report that they wanted to? Probably,” said Galbreath. “We stopped everything and I wrote a get-well plan.” It included returning to the cadets who visited the office in the past year to ensure they got the necessary help.

The Air Force Academy’s superintendent, Lt. Gen. Jay Silveria, is increasing staff from five to eight. He added a separate sexual assault response coordinator for the 10th Air Wing, which includes active duty forces nearby who had used the academy’s office.

Air Force Capt. Matthew Chism, an academy spokesman, said leaders are confident they have addressed the issues in the office. He said they will “continue to scrutinize our efforts and remain transparent as we strive to develop a culture of dignity and respect at the academy.”

Galbreath said he recommended all military service leaders increase oversight of sexual assault prevention offices.

There are five U.S. military academies in all. The U.S. Coast Guard Academy in New London, Connecticut, and the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, which is in Kings Point, New York, and run by the Transportation Department, aren’t included in this report.