The Army has made no secret of the fact that recruiting high-quality soldiers is only getting tougher.

Estimates are that just about 1 percent of young Americans are likely to join the Army, after subtracting more than 70 percent of citizens ages 17 to 24 who can’t meet the requirements.

But the Army is going to have to figure it out, because the service is on track to grow to more than 500,000 active-duty soldiers by 2022, while the economy continues to improve, and ― research shows ― fewer and fewer young Americans are considering the military as a job option.

“The Army’s recruiting mission is larger than all of the other services combined,” Brig. Gen. Joseph Calloway, the director of personnel management at Army headquarters, told Army Times. “That is a unique volume challenge.”

This year, that meant 76,500 new soldiers for the active component, which came down from the year’s original goal of 80,000. The service announced Sept. 21 that it had missed that target by 6,500, resulting in a net zero growth for the force in the previous year.

According to internal Defense Department surveys of young people people ages 16 to 21, interest in joining the Army has fluctuated a lot in recent years. In the months after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the number of young people who expressed serious interest in joining the Army surged from 7 percent to 11 percent.

That fell back down to 6 percent a few years later as the war in Iraq became unpopular. After the economic recession of 2008, interest rose again to 10 percent. But the latest surveys show it has fallen back to 7 percent.

With research showing that American youth’s propensity to serve is on the decline, the Army is confronting its challenges and all fronts.

That’s prompting the Army to take an array of measures to boost recruiting efforts, which includes sending hundreds more recruiters out into the field, boosting the overall recruiting budget, finding a new slogan (to replace “Army Strong”) and even buying new furniture to redecorate recruiting stations across the country.

Follow the money

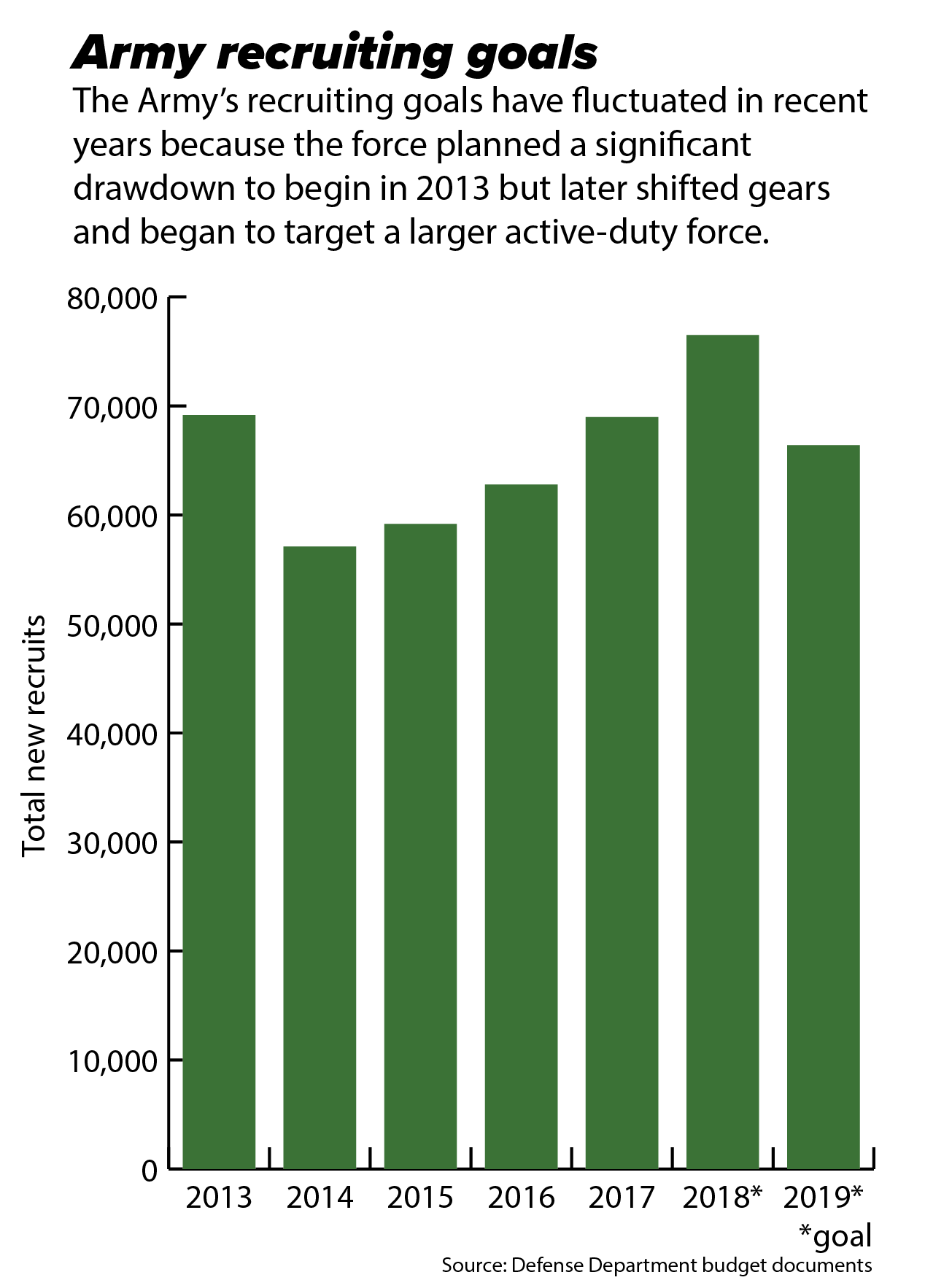

Army recruiting goals have been all over the map in the past several years, thanks to a planned drawdown after the end of combat deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan.

But operational tempo didn’t let up much, so in 2017, the service reversed course and began rebuilding its numbers, bringing the active, Reserve and National Guard’s total force back up to over a million soldiers.

The active component’s 2013 recruiting goal of 69,000 dropped drastically to the high 50,000s in 2014 and 2015 before shooting back up to 68,500 in 2017 and then 80,000 in 2018, according to budget documents.

So far, the service is looking at 66,400 in 2019, according to the most recent National Defense Authorization Act.

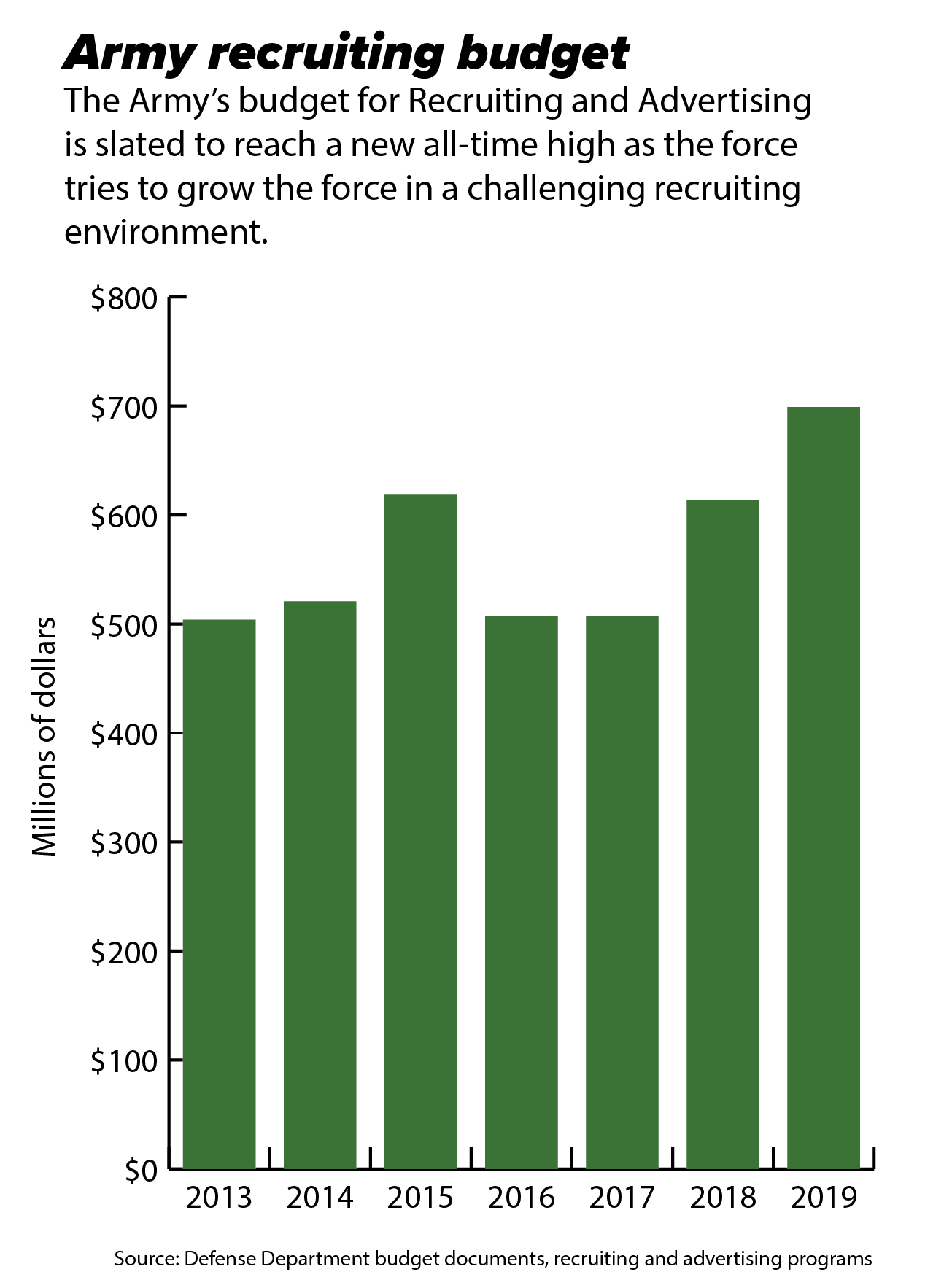

Recruitment spending has also jumped to match those goals. In 2013, the Army spent $121 million on enlistment bonuses. In 2017, it more than doubled $290 million. The final numbers aren’t in for 2018, but the estimate was $600 million, and the defense budget set aside $454 million for next year.

Most of those are smaller bonuses for a range of MOSs that change throughout the year, based on open spots in certain occupational specialties. For example, a Patriot Fire Control Enhanced Operator/Maintainer could net $40,000 with a six-year contract.

In total, the Army is looking at about $700 million sunk into recruiting in 2019, versus $500 million and under during the drawdown.

A new slogan?

Meanwhile, the Army Marketing and Research Group ― which is responsible for recruiting commercials, social media outreach and figuring out how to speak to young people ― has been under a microscope this year.

A 2016 Government Accountability Office study and subsequent internal audits this year found that AMRG had been burning through hundreds of millions of dollars with little discernible success.

The group spent $38.6 million on 20 programs in fiscal 2016 that “needed improvements to demonstrate they met their intended purpose,” according to an Army Audit Agency report released in April, which Army Times received via a Freedom of Information Act request.

The audit also found that AMRG didn’t have specific goals laid out to measure long-term effects of its spending, didn’t coordinate local and national marketing efforts with Army Recruiting Command and Cadet Command, didn’t have a good review process to measure effectiveness of its programs and didn’t have a process to verify the accuracy of performance data in its marketing programs.

“In coordination with leadership, we are taking a comprehensive look at our organization and the Army’s marketing strategy, and began to execute against the AAA audit recommendations to improve program return on investment and contract management,” AMRG spokeswoman Alison Bettencourt told Army Times.

Specifically, the group is piloting a program that will better integrate national and local marketing efforts, she said.

They will also “focus more on digital marketing, to include reworking our platforms to ensure they are mobile-first in their design and relevant to today’s prospect audience," she said.

Speaking of today’s prospects, senior leaders have sounded the death knell for “Army Strong.”

"I think we’ve just got to arm the influencers in America with the right information about what it is to serve in the Army, and I don’t think we’ve been doing that,” Sergeant Major of the Army Dan Dailey said in July.

A new recruiting strategy will need a new logo, but there are few hints so far about what that will be.

“In concert with leadership, we are working a way ahead. It is too early in the process to say more, but we understand the desire and need for a tagline, and we are moving out to ensure the work is done right and as expediently as possible,” Bettencourt said.

Fixing the gaps

While the 2018 recruiting goal turned out to be manageable for Army recruiting, one of the bigger hurdles was a shortage of recruiters themselves.

Back in April, senior leaders had considered a plan to send noncommissioned officers with previous recruiting experience to man stations on a temporary duty basis, in the face of a 400-recruiter shortage.

Soon after, a memo from a recruiting battalion commander in Texas leaked a proposal to extend night and weekend hours to make numbers.

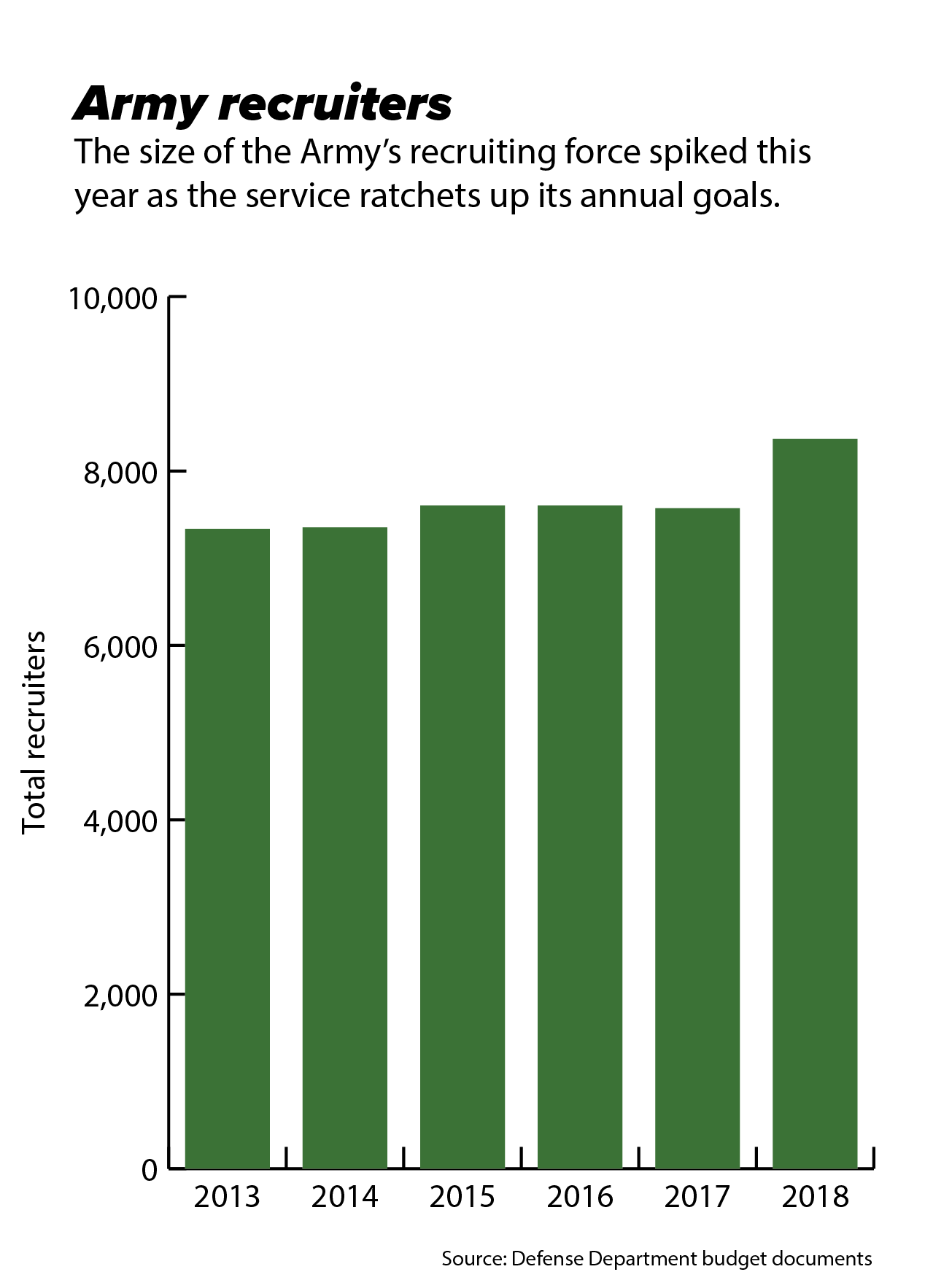

The problem, officials said, was that the Army had ramped up its recruiting mission in 2017 by 6,000 ― but they couldn’t grow the recruiting force instantaneously.

“Their structure was not set to meet that mission at the beginning of the fiscal year,” Calloway said.

Specifically, the Army was authorized for 8,367 recruiters in fiscal 2018, but by late July was at 96 percent fill with 8,074. The previous year saw a 99 percent fill, but that was 7,463 out of 7,573 spots for similar recruiting goals.

Even with room for more, it takes about nine months to identify NCOs who are eligible for recruiting, send them to school and then move them and their families to their new assignments.

“That was a big part of the challenge of increasing the size of the recruiting force this year, but we are now there,” Calloway said.

To avoid another shortfall and all the turmoil that can accompany it, he added, the Army is now budgeted to support a 72,000-a-year recruiting goal. That means not only 8,300 recruiters in the field, but a proportionate number of space in initial entry training and number of cadre to support them.

The Army is also offering up extra bucks to recruiters who stay on past their required three years. In October, Training and Doctrine Command Sgt. Maj. Timothy Guden told Army Times that the Army was looking to offer several hundred dollars a month extra to recruiters who extend their orders a year.

And for prior recruiters looking to get back into the game, there will be opportunities to return to recruiting and possibly re-classify to the MOS.

Recruiting stations

So now that the Army’s got enough recruiters to handle its recruiting mission, attention is turning to making the service more attractive to that small sliver of able and interested Americans who have choices when it comes to signing up.

At the top of the list is replacing scuzzy old furniture and jazzing up recruiting centers nationwide. The Army sank $50 million this year to revamp outdated offices and places where recruiters first meet prospective soldiers, Calloway said.

"Mom or Dad or coach or the applicant walks into a recruiting station that isn’t up to par, and it’s got 1950s grey furniture in it — they’re like, ‘I think you want to go Air Force,’ " he said.

The Army wants potential recruits to have a good impression of the Army, and a professional environment for its recruiters, he said.

“$50 million across the entire country, obviously, doesn’t cut it,” he added. “So they’ll have to continue to upgrade.”

Record retention

Despite recruiting challenges, however, the Army is catching a break from its historically high retention numbers ― 86 percent this year, from the typical 81.

That could provide some wiggle room, Calloway said. It’s also an incentive to keep standards high, he added.

“They’re more propensed to remain, they have a smaller drop-out rate in their training — so it pays in the long term to have a higher quality recruit,” he said.

Top officials share that sentiment.

“It could be in the future that you recruit fewer soldiers because you have less attrition,” Lt. Gen. Thomas Seamands, the Army deputy chief of staff for personnel, or G-1, told reporters in July.

RELATED

In recent months, Army Secretary Mark Esper has made some changes to the recruiting waiver process where it concerns past mental health problems or recreational drug use, a move that could widen the pool of millennials and Gen-Zers who have grown up in a culture where they are more likely to be treated for behavioral issues as well as in states where marijuana is legal.

But Esper has also reduced the Army’s cap on lower-quality recruits to 2 percent.

“If you come up with a waiver, we want to see that you bring other things to the table to make you really worth considering the waiver,” he said of recruit quality in August.

And perhaps, in a roundabout way, more retention of quality soldiers could help the Army solve some of its recruiting issues.

“The delta could be made up next with a lower recruiting mission,” Calloway said.

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.