The Pentagon wants to bring back mobile nuclear reactors to power forward bases and is asking industry how to make that happen.

A collection of scientists that closely monitor nuclear issues thinks that the concept is “naive,” dangerous and describes the chances for the current technology to accomplish what the Pentagon wants as “vanishingly small.”

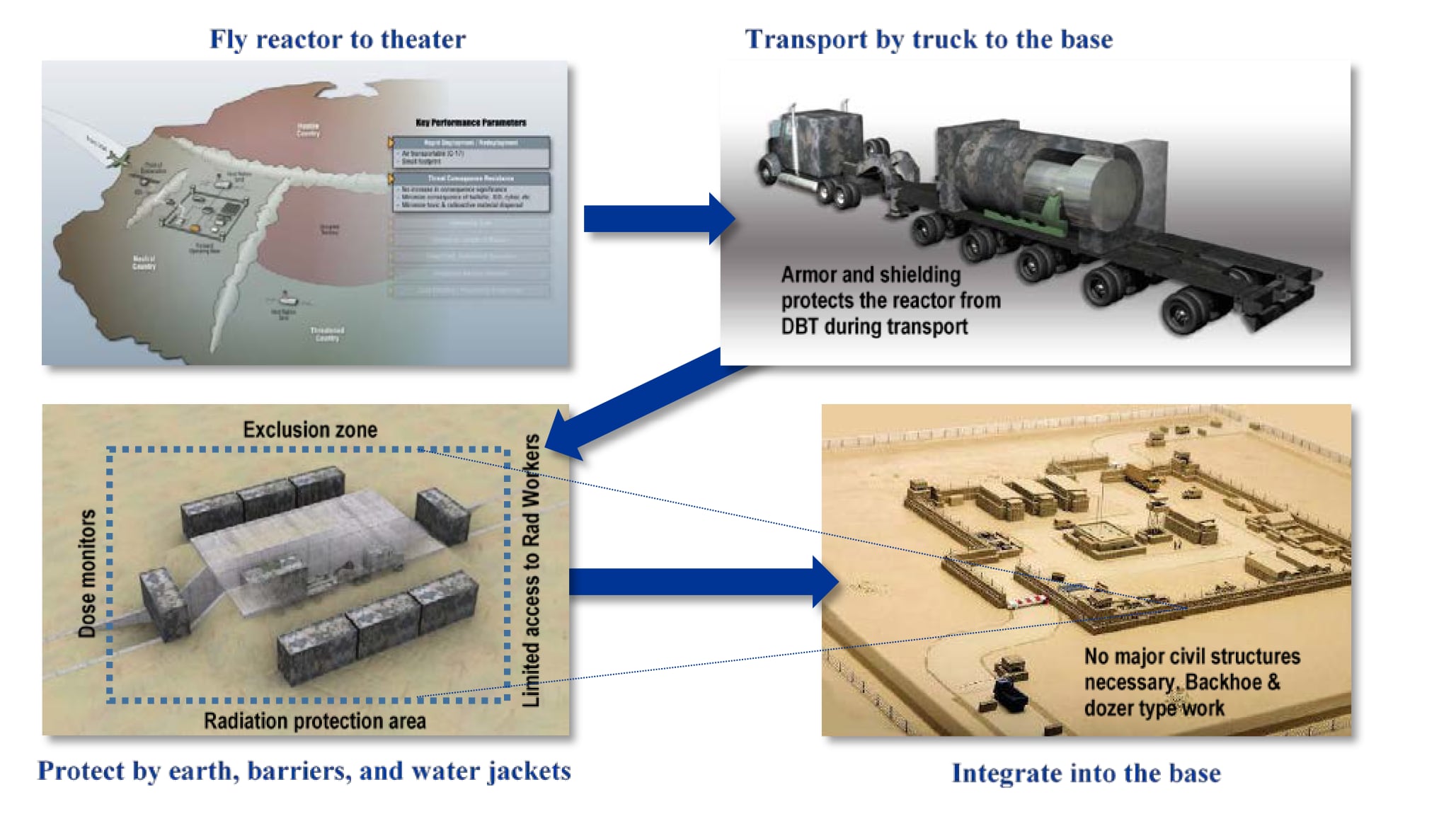

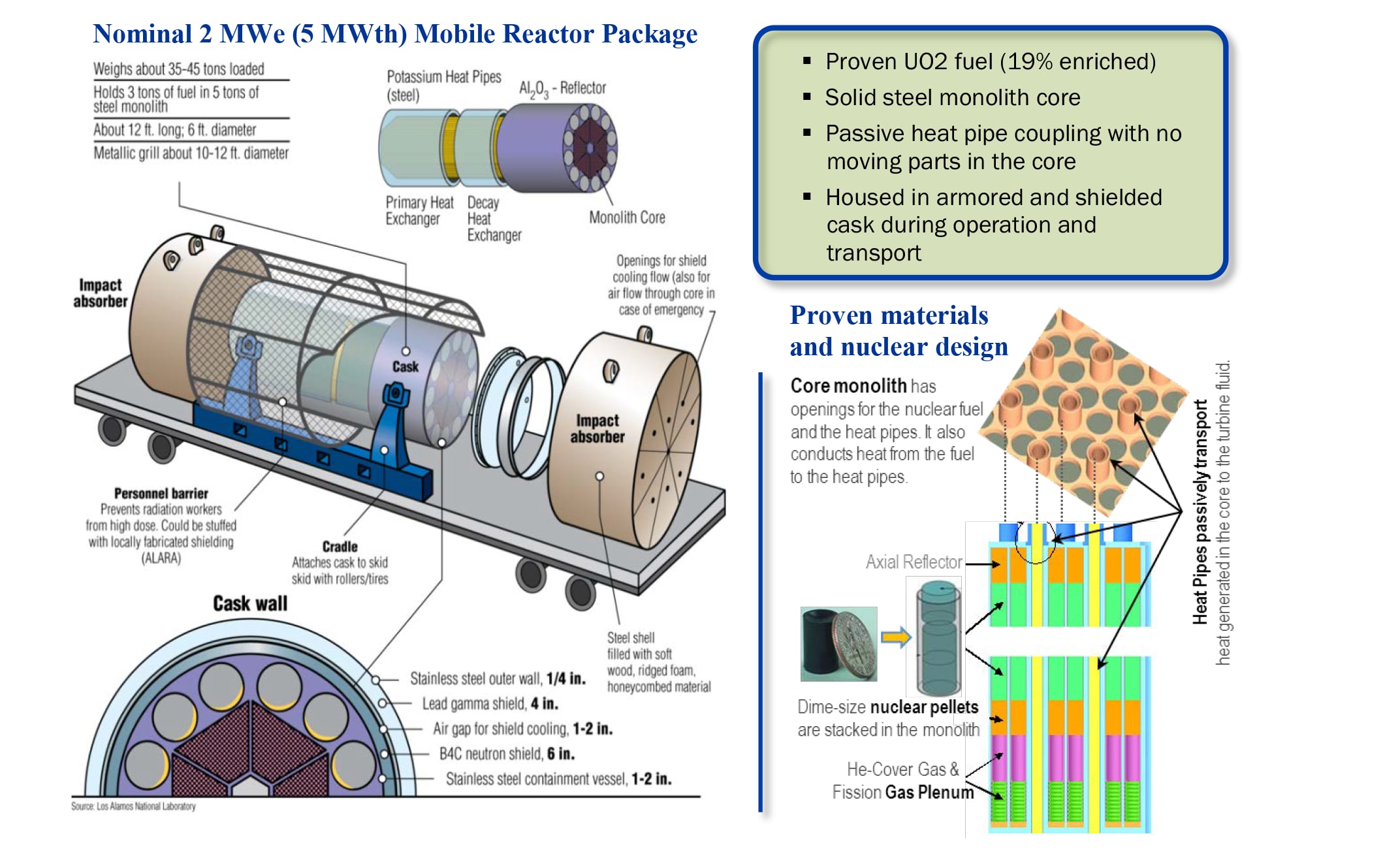

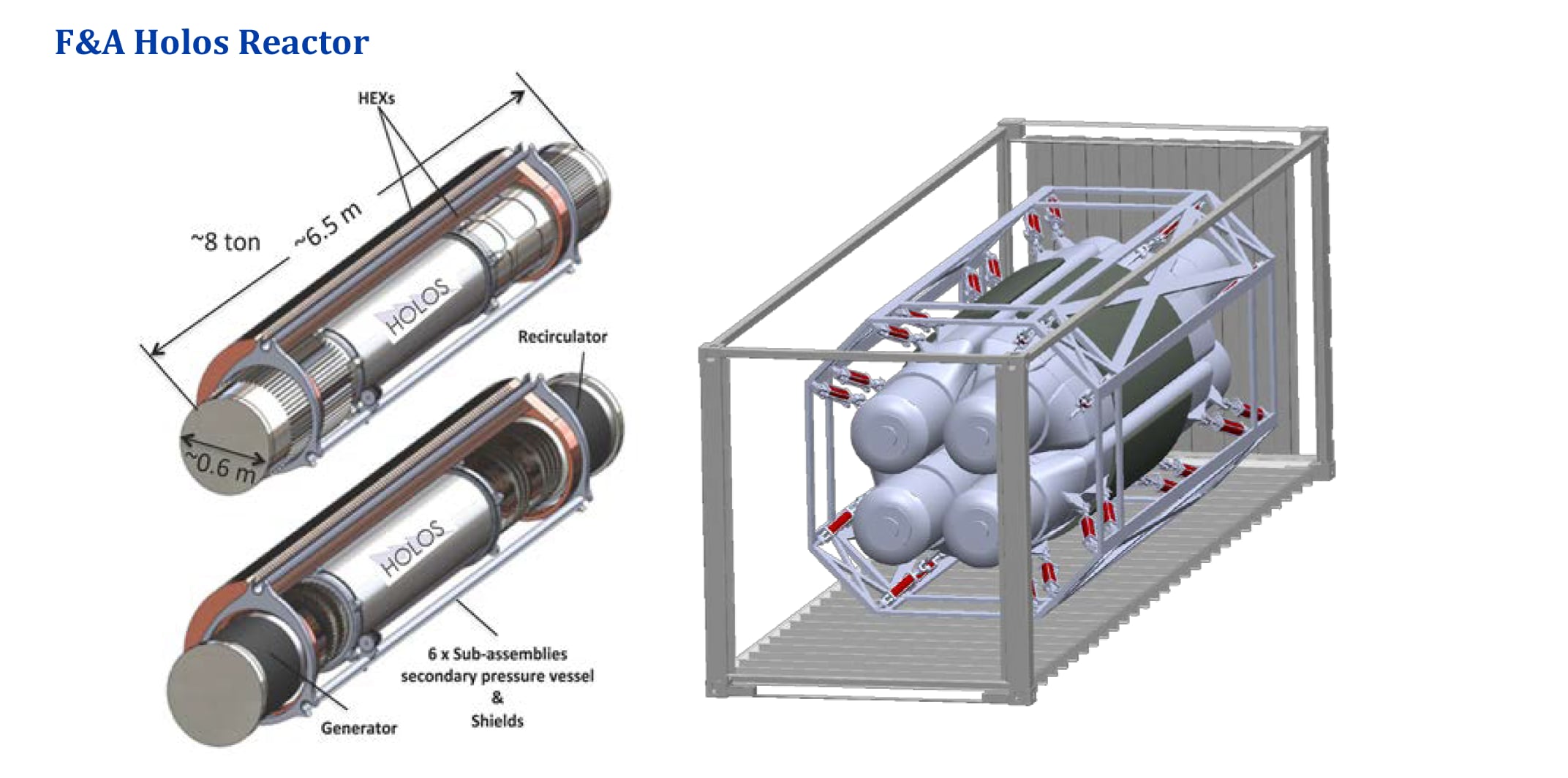

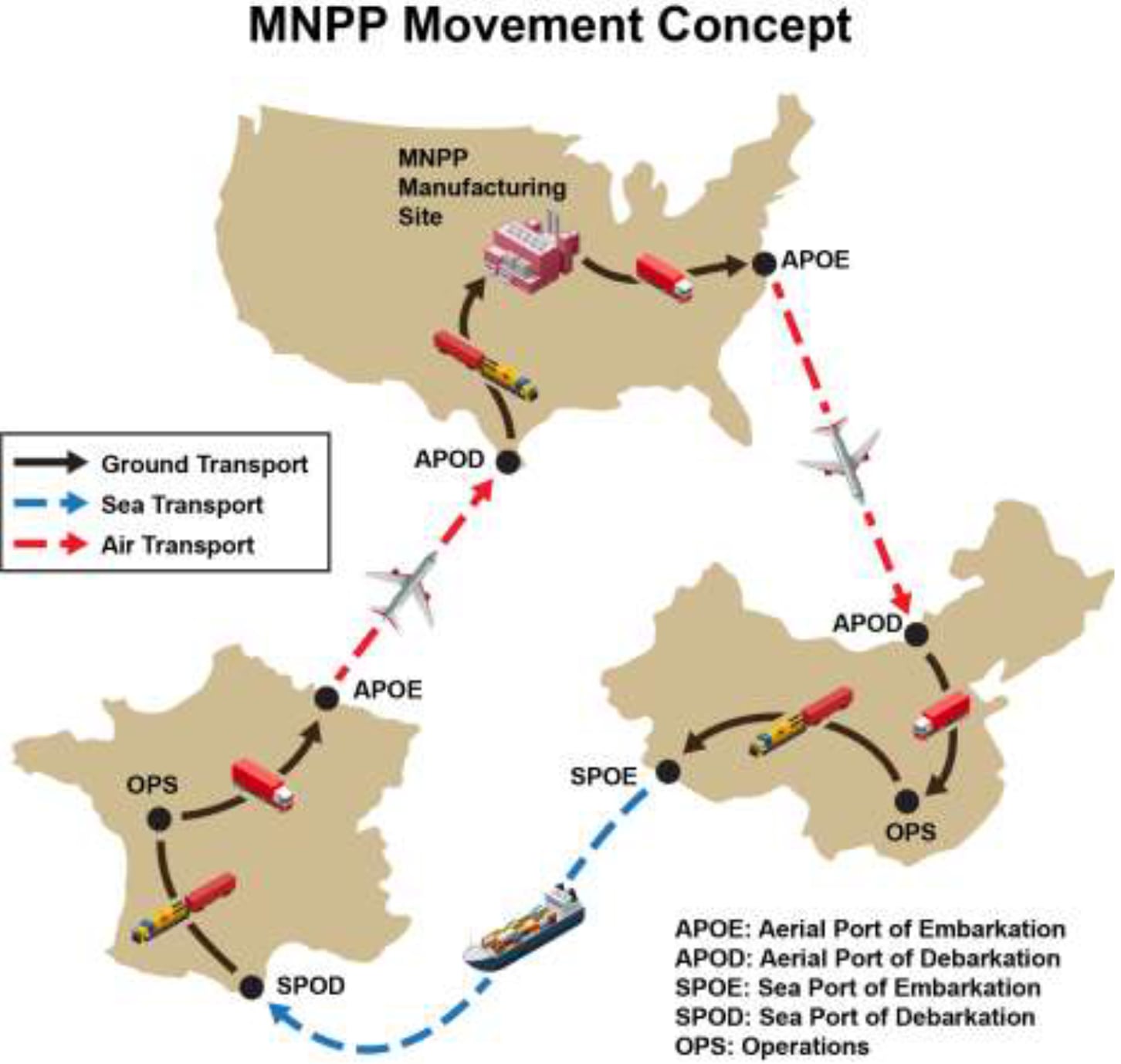

In January, the Pentagon’s Strategic Capabilities Office posted a request for information on the government website fbo.gov asking for information from industry on how companies might provide a less than 40-ton small mobile nuclear reactor design, capable of operating for three years or more and putting out 1 to 10 megawatts of power.

Dubbed “Project Dilithium,” a nod to the fictional dilithium crystal, a fuel source that powered warp drives in the Star Trek films and television series.

RELATED

SCO sees these devices as having the “potential to be an across-the-board strategic game changer” by saving lives and money through saving fuel and the associated transport and long logistical tail required to power modern combat operations.

Recent studies and reports do provide passing references to ensuring the reactors have “inherently safe designs,” are built in ways to make it so that the meltdowns are “physically impossible” and that any version of a reactor can be ruggedized.

But Edwin Lyman, acting director of the Nuclear Safety Project at the Union of Concerned Scientists, noted that the Army’s own study showed the devices would “not be expected to survive a direct kinetic attack.”

Lyman acknowledges the Army’s need to save fuel, reduce convoys and transports and minimize attacks on those elements of the force. But, he also argues that adding reactors to the battlefield could create more problems than it solves.

In a lengthy response to the program posted on the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists website, Lyman outlines the scientific, safety and policy problems with developing and deploying a small mobile nuclear reactor.

But he closes with his analysis that the nuclear ambitions of the ground forces are part of a “patient, decade-long effort by nuclear lobbyists” aimed at gaining the interest of both the Pentagon and Congress to be “the savior small nuclear reactor vendors need: deep-pocketed and unbeholden to return-seeking investors.”

He implores defense officials to “pull the plug on this misguided effort.”

In his post he points out that the two emergent technologies identified by defense research ― Los Alamos National Laboratory’s “MegaPower” Reactor System has major hurdles.

A 2017 study by the Idaho National Laboratory, a location that is used for testing “new and novel” reactor designs, found “several major safety concerns” with the MegaPower approach and two variants developed found similar safety flaws and “introduced some new ones.”

This initiative isn’t entirely new.

The Army Nuclear Power Program, which ran from 1954 to 1977, developed eight small nuclear reactors. Those reactors ranged in power production from 1 to 10 megawatts.

How five of the eight reactors were used:

- The PM-1 reactor was used in Sundance, Wyoming, from 1962 to 1968.

- The PM-2A was used at Camp Century, Greenland, from 1961 to 1964.

- The PM-3A was used at McMurdo Base, Antarctica, from 1962 to 1972.

- The ML-1 was used in developmental testing from 1962 to 1966.

- The MH-1A Panama Canal Zone from 1965 to 1977.

Lyman notes a major failure with one of the original eight designs in 1961 when a core meltdown and explosion of the ML-1 reactor in Idaho killed three operators.

The three deployed to Antarctica, Greenland and Alaska proved “unreliable and expensive to operate,” Lyman wrote.

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency issued its own RFI in 2010 and then budgeted $10 million in fiscal year 2012 to develop a nuclear reactor program. The agency proposed a $150 million program over six years to build the mobile reactors.

That initiative died for lack of funding due to restrained overall defense budgets.

The idea was resurrected by the National Defense Authorization Act for FY 2014, in which Congress asked for a report on a “small modular reactor” to power forward or remote operating bases.

A Defense Science Board task force then published a detailed report in 2016 outlining the power requirements that could be met with such hardware. Last year, the Army’s deputy chief of staff, G-4, published a 148-page study on the use of mobile nuclear power plants for ground operations, adopting the recommendations of the 2016 Defense Science Board and further advocating, as the board did, that the Army manage ground nuclear reactor programs and pursue existing or near-to-maturity technologies.

Last year’s Army G-4 report outlined a dozen existing locations that officials think could have power provided by the type of mobile reactor they’re seeking:

- Thule, Greenland

- Kwajalein Atoll

- Guantanamo Bay, Cuba

- Diego Garcia

- Guam (for both a naval and Air Force facility on the island)

- Ascension Island

- Fort Buchanan, Puerto Rico

- Bagram Air Base, Afghanistan

- Camp Buehring, Kuwait

- Fort Greely, Alaska

- Lajes Field, Azores

The Pentagon timeline for getting this tech running isn’t a long one.

The deputy was aiming for a demonstration date by 2023. The Idaho National Laboratory estimated that demonstrations could begin as early as 2021.

The RFI doesn’t lay out details but does note that the Defense Department could pick three prototypes for its phase I portion of development. That would require prototype designs and other plans. That phase would go for nine to 12 months, according to the post.

Then, in phase II, those selected would begin acquiring materials and building their prototype reactors for testing and evaluation.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.