In the three weeks since Maj. Gen. Patrick Donahoe took command of Fort Benning, Georgia, the base has seen one soldier die by suicide and three more make “desperate attempts,” he tweeted Monday.

It’s an issue present throughout the military, the result of a variety of factors including a high-stress environment, PTSD, and traumatic brain injuries. And it’s an issue leaders are wholeheartedly trying to solve.

“We’ve got to convince everyone wearing the uniform that if you’re faced with those kinds of thoughts and decisions that there is no shame, no stigma to reach out,” Donahoe told Military Times.

The Defense Department’s most recent statistics stated a suicide rate of 29.5 per 100,000 for active duty Army personnel in 2018. That’s 4.7 deaths per 100,000 higher than the suicide rate for the military as a whole.

The civilian suicide rate in 2018 was 14.2 per 100,000, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention reported.

Donahoe’s approach to preventing suicides at Fort Benning is two-pronged: leaders need to practice empathy and recognize the signs, and every soldier needs to be prepared to connect at-risk personnel with suicide prevention resources.

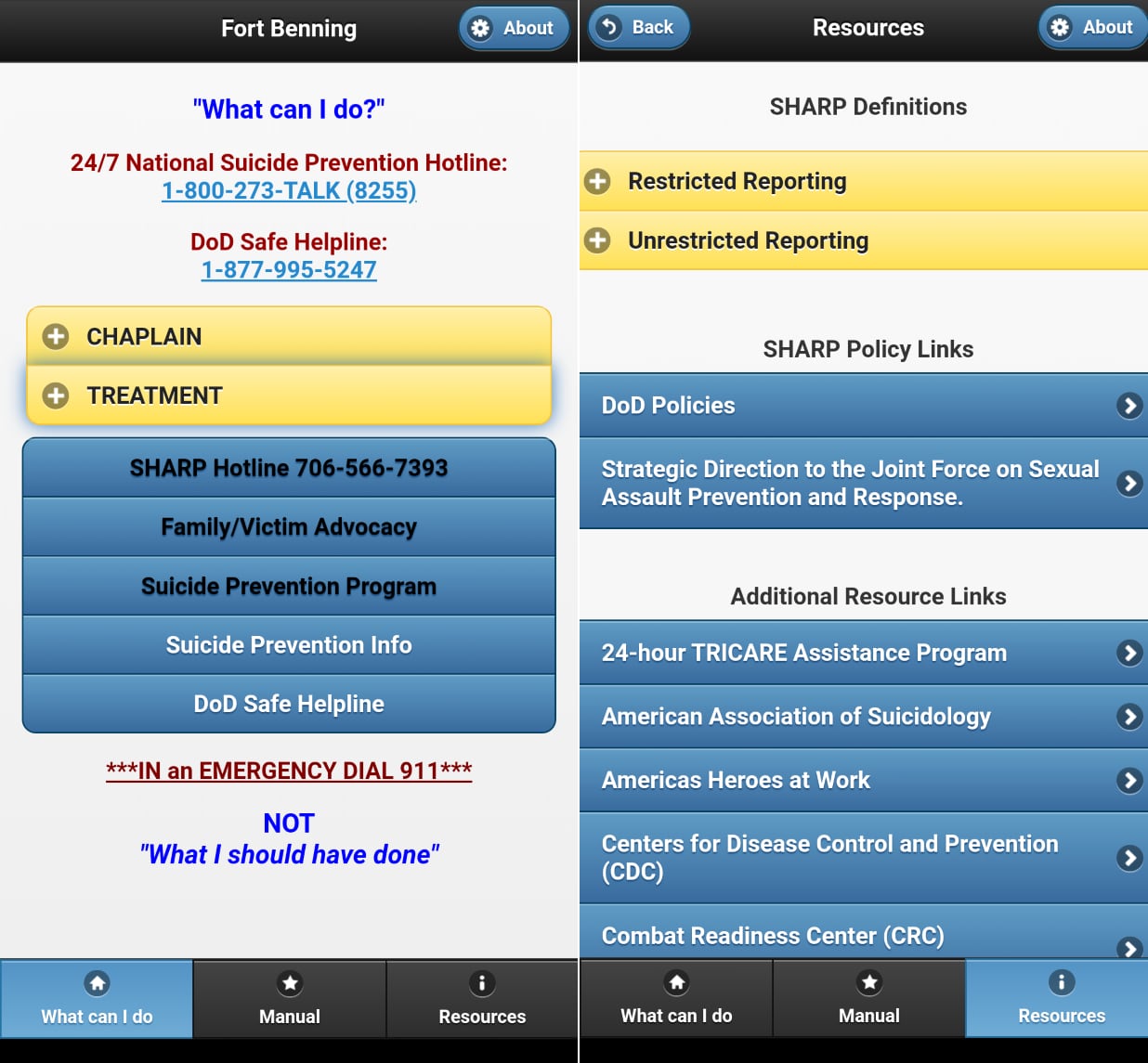

One suicide prevention resource he urges every soldier to download is TRADOC’s WeCare app.

Released in 2014, the suite of apps provides access to local and national resources for sexual assault and suicide prevention.

Currently, WeCare apps are available for 86 different installations around the world and boast a total of approximately 130,000 users. In early August, TRADOC made concerted efforts to increase awareness of the resources WeCare provides. A spokesperson told Military Times that the apps are regularly maintained to ensure information is up-to-date.

Upon opening the app, phone numbers for suicide hotlines, chaplains, medical treatment, and more are immediately displayed. Other tabs offer access to a variety of more specific resources and the Army’s suicide prevention manual.

Connecting soldiers with the right resources at the right time could prevent future suicides like the Fort Benning soldier who took his own life, Donahoe said. The soldier who died by suicide was a member of the base’s training cadre — “the picture-perfect sergeant,” as Donahoe called him.

A rapid series of negative events combined with alcohol led him to believe that his only way forward was to kill himself with a gun, said Donahoe.

The major general wants soldiers to be “positively intrusive” in these scenarios, reassuring those at-risk that it’s okay to seek help.

“We’ve got to be spring-loaded, and that’s the purpose of that app,” he said. “You can just open that app up, hit a button, and be talking to a suicide prevention specialist.”

But sharing resources isn’t always enough, and soldiers don’t always have access to their phones. That’s where Donahoe’s focus on empathy comes into play.

The basic training environment can be especially stressful for new recruits, Donahoe said, and empathy from leadership there is absolutely crucial.

The three young soldiers at Fort Benning who attempted to take their own lives were all trainees in the first few weeks of basic combat training or one-station unit training.

“Our drill sergeants, our company leadership in the OSUT environment have got to have their sensors out for folks who are not adjusting well,” said Donahoe.

The overwhelming and isolating feelings trainees experience when trying to quickly adapt to life in the military are only exacerbated by the current pandemic.

Just as it’s been done for decades, trainees arrive at Fort Benning by the busload and are thrown into an intensely stressful environment. But unlike the decades of trainees before them, these recruits could be placed in quarantine for weeks upon arrival, unsure of what’s going to happen to them next.

“We’ve got to remember what it was like to join the Army and show up to your first Army event, and then on top of that the added stress of either you are COVID positive or might be,” said Donahoe. “We’ve got to lean in and make sure that these young people understand that they’ve got an entire system wrapped around to care for them.”

The major general made it clear that preventing suicide is a top priority, even if it means an end to a soldier’s service.

“If the way to prevent them from trying to kill themselves is to get them on a pathway out of the Army, then we’ve got to do that,” he said. “We’ve got to change the culture.”

If you or a loved one is experiencing thoughts of suicide, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, 1-800-273-8255, which offers a crisis line specifically for service members and veterans.

Harm Venhuizen is an editorial intern at Military Times. He is studying political science and philosophy at Calvin University, where he's also in the Army ROTC program.