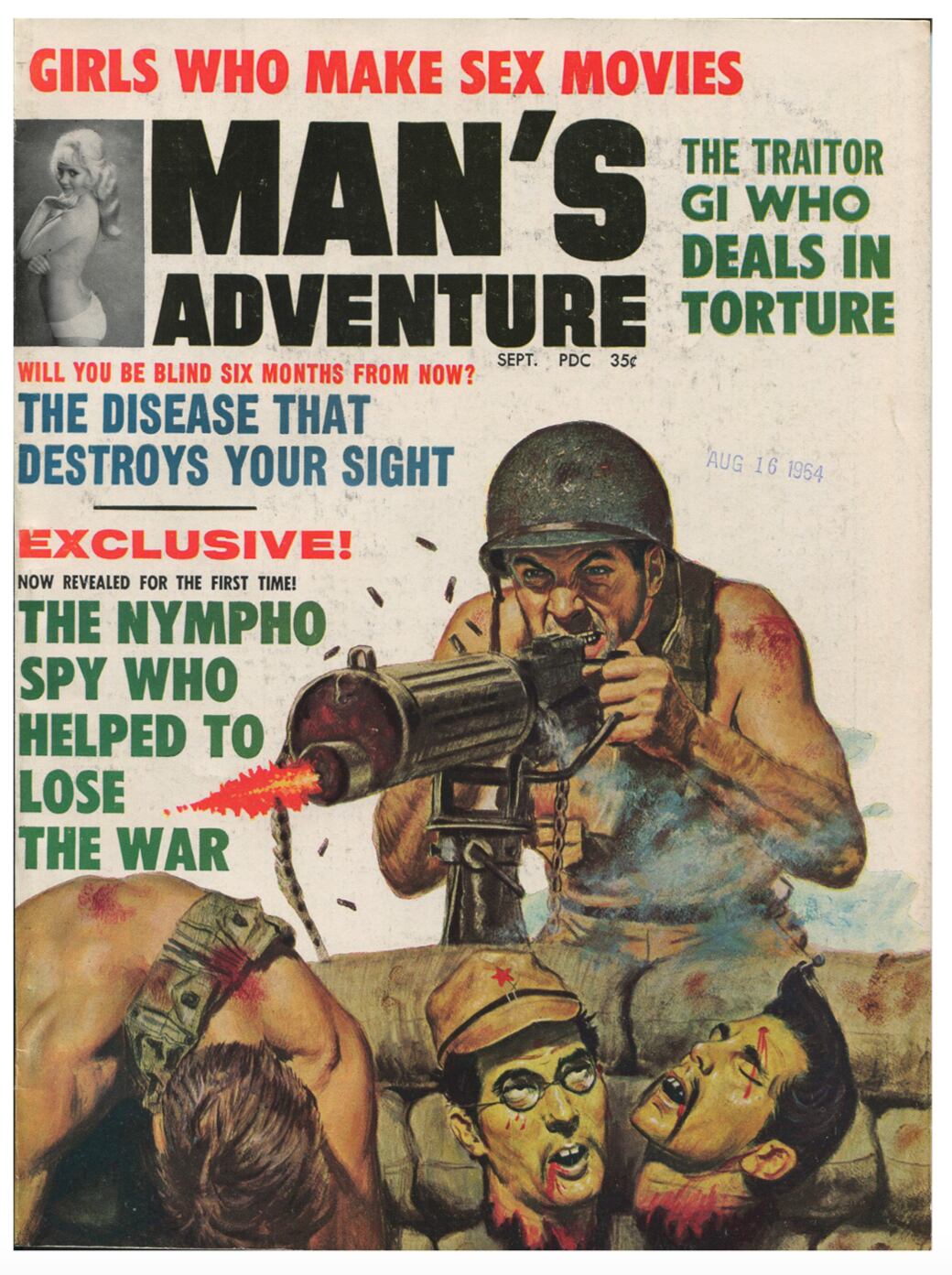

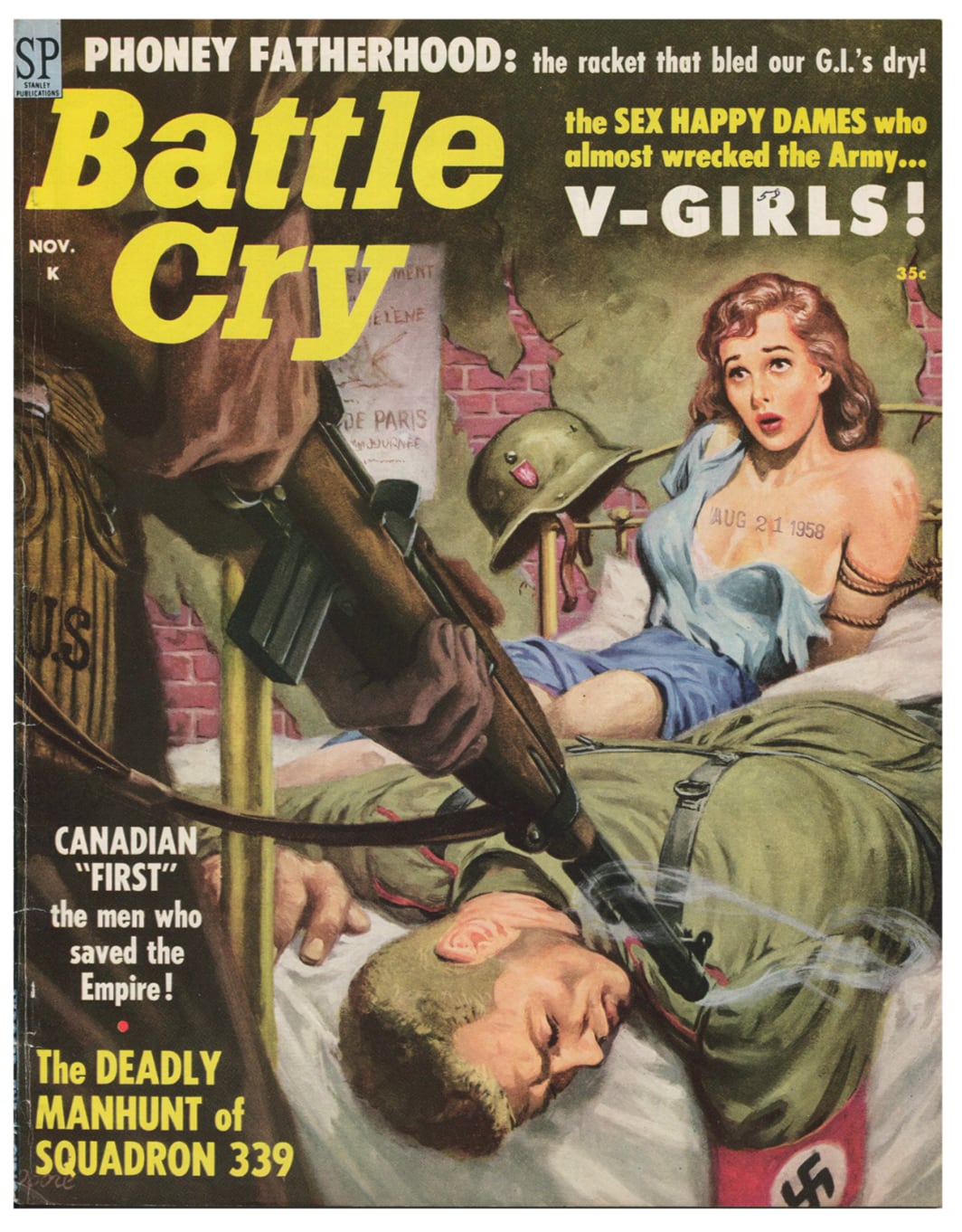

Buxom women rescued by hard-bitten Special Forces soldiers. An infantryman shielding the damsel in distress as the city burns and Nazis roll through the streets. Bare-chested men firing machine guns at unrelenting commie hordes.

Such graphic illustrations were accompanied by titles like “Battle Cry,” “True Man,” “Man’s Epic,” and “Man’s Adventure,” and featured sensationalized phrasing such as “I’m Not Afraid of World War III,” “Night of the 30 Virgins,” and “The Nympho Spy Who Helped to Lose the War.”

RELATED

These were men’s pulp magazines, replete with sex, war and heroism — and they were anything but niche material. Pulp mags filled the racks and subscription lists of thousands of men and teenage boys across America in the post-World War II publishing boom.

In fact, 13 of the top 20 best-selling magazines in the military exchange system were in the men’s adventure category in 1967, numbers that continued through at least 1969. And as low-brow and over-the-top as they sound, these publications shaped the perspectives of a generation of future military men when it came to expectations of combat — a noble cause, plenty of action and promiscuous foreign women.

Instead, what the generation raised on the pulps got was Vietnam.

That peculiar dynamic makes up the central thesis of a new book by retired Col. Gregory Daddis, titled “Pulp Vietnam: War and Gender in Cold War Men’s Adventure Magazines.”

Daddis, a West Point alumnus and career Army officer, served during Operation Desert Storm and Operation Iraqi Freedom. Once the chief of the American History Division at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, he now works as a history professor at San Diego State University and director of the school’s Center for War and History.

The retired colonel spoke with Military Times about the book — his second after 2017′s “Withdrawal: Reassessing America’s Final Years in Vietnam” — in which he details the pulp magazine rise between World War I and World War II, one that contributed to decades of stories on global conflict, sexual escapades, and heroism as a rite of passage.

Reflecting on reading the pulps as a boy, acclaimed author and Vietnam War veteran Philip Caputo once noted, “the heroic experience I sought was war; war, the ultimate adventure; war the ordinary man’s most convenient means of escaping from the ordinary.”

“I think that’s the tension between narrative and reality,” Daddis told Military Times. “That has always been there. We tell war stories to ourselves in ways that I think are almost aspirational. We want war to be this way.”

Numerous noteworthy authors were found to have contributed to the pulps, including Norman Mailer and Mario Puzo, who would later write “The Godfather.” Military historian Richard Tregaskis, as well as author and veteran Robert Leckie (”Helmet for My Pillow”), also published bylines.

At times, pulp magazines letters-to-the-editor pages served as a kind of early social network, with veterans sharing wartime experiences, though much could be characterized as “sentimental militarism.”

The pulps reinforced “narratives where traditional accounts of battlefield combat remained central to waging war, all while offering readers a supposedly tried-and-true method for attaining their manhood,” Daddis notes. “There was one problem, however. Vietnam failed to deliver.”

Heroic notions of combat would, for many, soon be shattered by the brutal realities of fighting a confusing, unpopular jungle war against an adept and oftentimes invisible enemy. Still other harmful messages continued to be delivered in those pulpy pages, Daddis said.

“Men’s adventure magazines fostered an implicit consent of sexual subjugation by defining militarized masculinity as embodied in both the battlefield hero and the sexual conqueror,” Daddis wrote.

Unit newspapers routinely mimicked the pulps, spilling pages of ink on combat bravery among the troops while never failing to include a pinup-ready girl. There was the Army’s 25th Infantry Division newspaper, “Tropic Lighting News,” for example, which not only included a regular appearance by the “Tropic Lighting Girl,” but once featured the caption, “Her name is unknown to us but then, is it really that important?”

For emphasis, Daddis draws on testimony from veterans during the war. One such commentary came from Marine Lance Cpl. Thomas Heidtman during a January 1971 anti-war event in Detroit, where he claimed to have witnessed frequent instances of troops ripping off a woman’s clothing, “just because they were female and they were old enough for somebody to get a laugh at.”

Scholars like Rhonda Copelon and Duke University’s Madeline Morris argued that war intensified and enabled such brutality and the likelihood of sexual assault, as described by Heidtman.

But as the Vietnam War aims failed and support waned, so did readership for pulp magazines. By the late 1960s and into the early 1970s, a “new generation of draft-eligible youths were questioning the orthodoxy of war as a man-making experience,” Daddis notes. That challenged a central tenet of the magazines.

“The pulps could no longer attract readers from a society uneasy with, if not mobilized against, hypermasculine images and bloody war stories,” he wrote.

The content seemed to split. Stag magazines and pornographic publications such as “Playboy” and “Hustler” focused explicitly on sex, while other periodicals branched off to construct a different image of military adventure.

“It is no coincidence that ‘Soldier of Fortune’ magazine started in 1975, not long after traditional adventure magazines, combining war and sex, had fallen out of favor,” Daddis wrote. By 1980, “Soldier of Fortune” was publishing classified advertisements for would-be mercenaries, he added.

Though a generation removed from Vietnam, Daddis acknowledged it was a similar promise of adventure that led to his own 1985 journey to West Point. During his career, however, there was a shift in the concept of military service, he said.

In the wake of the Vietnam War there was the idea that veterans were coming home broken, possibly riddled with drugs or a danger to society, Daddis said. But under the administration of President Ronald Reagan, the narrative switched to one of noble warriors fighting for a just cause. Then came new iterations of hyper-masculinity — Chuck Norris movies, Rambo films, and more.

“I remember watching “Full Metal Jacket” as a kid, thinking that drill sergeant experiences were going to be the same thing,” he said.

But fairly early into his service, that story fell apart, Daddis admits.

He served with the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment in the Persian Gulf War, and though his return home was met with cheering Americans, there was little to feel heroic about, not while many of his fellow soldiers in the late 1980s and early 1990s saw little or no combat. Additionally, there were still units at the time, even in Daddis’ first scout platoon, that had Vietnam veterans in their ranks.

Using history and his own experience, Daddis ultimately challenges readers to move beyond those popular conceptions of “normal” male behavior, to “think more deeply about how we remember and how we portray war in our popular culture. Young men often find meaning in images and structures of male superiority, especially when the protagonist is a bold, heroic warrior, he said.

“How we remember war matters, and the ways in which we look back upon the past have consequences,” Daddis wrote.

“War need not be the only, even primary rite of passage into manhood.”

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.

In Other News