Staff Sgt. Randall S. Hughes got off with a slap on the wrist after he raped the wife of a young soldier under his charge during a Super Bowl party in 2017.

It wasn’t the first time Hughes raped someone, according to charge sheets, and it wouldn’t be the last.

The victim, Leah Ramirez, reported the rape to Army CID the next day. It happened after a party held at Ramirez’s home near Fort Bliss, Texas. Ramirez’s husband was passed out drunk after Hughes had egged him on to continue taking shots of whiskey throughout the evening.

Ramirez put her husband to bed, the party ended and everyone else left. Ramirez was outside alone with Hughes when he propositioned her for sex. She said no, so Hughes grabbed her, forced himself upon her against a grill and later dragged her by the hair into her home where he raped her, she said.

After it ended, Ramirez hid in a bathroom until Hughes eventually left the house.

“I waited until the morning and then I went to the hospital to get checked,” she recalled. “It took CID 48 hours to get into my house for evidence, so I lived in the crime scene for 48 hours. And then, it took three years to do anything.”

‘This is how it is’

After a year-long investigation, Army CID agents determined the allegations were credible. But Hughes’ brigade commander decided against prosecution in August 2018, according to an Army official familiar with the case who declined to name the brigade commander.

At that time, the official said, there were no other reports of misconduct about Hughes. The same year he escaped prosecution, Hughes’ name appeared on the sergeant first class promotion list.

Ramirez learned of the pending promotion and complained to the commander of Fort Bliss at the time, Maj. Gen. Patrick Matlock, who then gave Hughes a General Officer Memorandum of Reprimand. The GOMOR, an administrative letter documenting misconduct, effectively stopped the promotion.

Ramirez’s husband had changed posts while the investigation unfolded, and it didn’t seem like there was much left she could do.

“I was told CID had enough evidence to believe it happened, and Fort Bliss still didn’t do anything,” she said. “They just told me the command said this is what it was — this is how it is.”

The Army would later learn that Hughes was a serial rapist. A few months after Ramirez reported her rape, Hughes did the same thing to another woman at Fort Bliss, according to court documents.

Hughes transferred to Fort Dix, New Jersey, in the intervening years. It wasn’t long before he was once again accused of rape — this time by his teenage daughter. But now, Fort Dix CID agents saw the GOMOR in Hughes’ file, and in 2020 they began looking into his past.

That CID inquiry ultimately resulted in criminal charges spanning more than a decade and involving five victims. A plea agreement whittled the charges down to a few of the most recent incidents, but still included both 2017 rapes.

RELATED

On March 30, Hughes pleaded guilty in a Fort Drum, New York, courtroom to a slate of criminal charges and was sentenced to 13 years in prison and a dishonorable discharge.

Hughes pleaded guilty to two counts of rape, two counts of sexual assault consummated by battery, one count of sexual abuse of a child, one count of assault consummated by a battery on a child, one count of indecent language and one count of adultery, according to court records.

Victims in the case said the crimes committed at Fort Dix could have been stopped if the Army prosecuted Hughes in 2017.

Several of the women spoke to Army Times about Hughes and explicitly asked that their names be included in this article, prompting a break from the normal practice of not naming victims of sexual assault. The women said they believe more of Hughes’ victims remain out there, fearful of coming forward or unaware that anyone cares.

Commands ‘rarely’ send cases to court

Hughes’ repeated rapes and the Army’s failure to investigate and prosecute them aggressively raises troubling questions about how the service handles sexual assault complaints.

Hughes’ case also comes to light at a time when the military as a whole is bracing for a new push from Capitol Hill to strip commanders of their authority over sexual assault cases and instead turn those cases over to civilian prosecutors.

“Our hearts go out to these victims, and we are thankful there was enough evidence to prosecute him, convict him of serious offenses and sentence him to a lengthy period of confinement,” said Michael Brady, the Army’s principal deputy chief of public affairs, in a statement to Army Times.

“While the Privacy Act precludes us from commenting on specific cases, it’s important to note that a probable cause finding is not a final determination there is sufficient evidence to prosecute,” Brady added in response to questions about why Hughes only received a GOMOR after Ramirez’s complaint.

The failure to prosecute sexual misconduct cases is more the norm than the exception in the U.S. military, said retired Col. Don Christensen, former chief prosecutor for the Air Force and current president of Protect Our Defenders.

RELATED

“Despite the persistent myth that suspected military sex offenders are prosecuted at a high rate, the reality is the chain of command rarely ever sends a suspect to court,” said Christensen, who testified before Congress last month on the issue of sexual assault in the armed forces. “Right now, I’d say the military is uniquely bad at evaluating the strength of an allegation. In the vast majority of cases, leadership decides to do nothing.”

When leaders take action against accused troops, suspects are charged in 49 percent of cases, according to Christensen. In roughly a third of those cases, the charges never make it to court. Commanders often hand down nonjudicial punishments and administrative actions instead, he added.

“[The command] should be horrified their failure to hold the rapist accountable enabled a sex offender to perpetrate a crime wave against multiple victims,” said Christensen, who was not part of the case against Hughes, after looking at the trial results.

Brady’s statement pointed to a Pentagon report from last year that reviewed penetrative sexual offenses in 2017. The report said there was “not a systemic problem” in whether the Army decides to prefer charges against suspects, and in nearly all the cases reviewed, the “decisions were reasonable.”

A history of abuse

The allegations of rape against Hughes date back to 2006, though that case was not reported at the time. Army investigators said Hughes raped his then-wife at Fort Carson in Colorado, but the charge was dropped as a part of Hughes’ plea agreement.

Years later, while Army CID was investigating the rape of Ramirez after the Super Bowl party, Hughes violently raped his then-girlfriend at Fort Bliss in the summer of 2017. Hughes later pleaded guilty to that rape.

But his plea agreement avoided charges that he told his then-girlfriend to not speak to agents who were investigating Ramirez’s case. Charges that he intentionally cut the woman using a broken glass bottle were also dropped as part of the agreement.

In late 2017, Hughes’ estranged 14-year-old daughter moved in with him.

Hughes had not been involved in the girl’s life previously, according to her mother, Chayla Madsen. But her daughter had gone through a difficult few years and wanted to make a change. Hughes quickly agreed, to Madsen’s surprise, but the mother was not aware of the rape allegations.

“I never had any idea something like this [investigation] was open, and obviously he did this to look like an upstanding single dad,” said Madsen, who praised her daughter for coming forward with allegations of sexual abuse. “I didn’t know he was being investigated … and Fort Bliss just allowed him to move a child — she was 14 — in with him and move on base.”

Victims ‘got lucky’ after the second report

Hughes behaved inappropriately toward his daughter at Fort Bliss, but his misconduct increased when they moved to Fort Dix.

On March 25, 2020, Hughes gave his daughter sleeping medication and raped her. Hughes’ plea agreement did not admit to that charge, but he did admit to sexual abuse and assault of a child.

“He was taking a plea deal, so he wanted to plead to get the minimum amount of years,” said Lesley Madsen, the now 17-year-old daughter who asked, with her mother’s approval, to be named in this article. “If I said no, then it would have been years of court. … It was the easiest way to give everyone that closure and just put him away before he did anything to anybody else.”

Lesley Madsen contacted her mom and then police about the abuse and inappropriate behavior, which ranged from offering the child drugs to sexual assault.

“I got really lucky and I had a team [of CID agents] who cared a lot … because they found everybody else and they started adding it all up,” she said. “It was just insane, because none of us even expected the extent of what he did” to others.

“I’m not ashamed of what he did to me,” she added. “I want people to know I’m a minor and I want them to know that I’m a daughter.”

Fort Dix CID agents stepped up in this case, the three women said, but Ramirez added that the military justice process before that was bungled.

RELATED

Ramirez’s complaint about Hughes’ impending promotion to sergeant first class stopped his ascension through the enlisted ranks. But it wasn’t until Ramirez complained that the GOMOR was issued, and it wasn’t until Hughes’ daughter reported him that everything changed, the victims said.

From the lack of prosecution that allowed more crimes to be committed, to the failure to keep victims informed, Ramirez said there are lessons for the Army to mine from this case.

“This is somebody who was supposed to protect my husband — our leadership,” said Ramirez. “And in all honesty, we do believe there are other victims.”

Ramirez’s husband is now a staff sergeant. He wants to be a career soldier, and the fact that Hughes is now behind bars provides some closure. But it hasn’t been an easy four years as he shuffled to new units at Fort Benning, Georgia, and Fort Hood, Texas.

“It’s hard for me to trust my chain of command now,” Staff Sgt. Arnulfo Ramirez III said. “It takes me forever, once I get to a new unit, to trust platoon sergeants. … Fort Benning earned it and Fort Hood has, so far, earned it.”

Hughes was still being held at Oneida County Correctional Facility in New York as of Thursday, jailers there said by telephone. He will ultimately be transferred to the U.S. Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to serve his 13-year sentence.

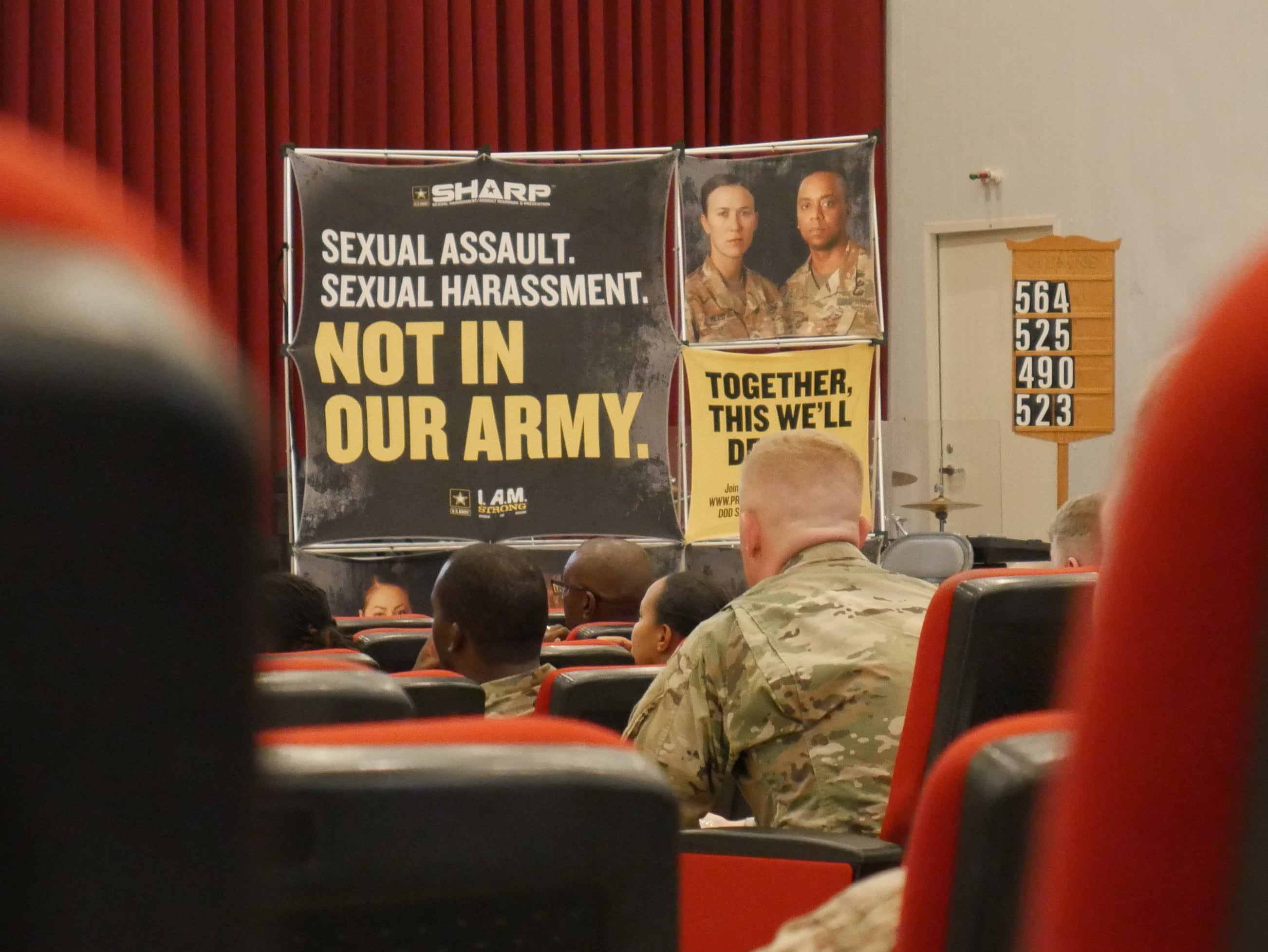

An Army task force is currently working to redesign the service’s Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention program, said Brady, the Army’s principal deputy chief of public affairs. SHARP came under scrutiny last year following an independent civilian probe that raised concerns about how the program is managed.

“We have significant work to do to regain our soldiers’ trust in our sexual harassment and sexual assault prevention program,” Brady added. “These efforts to redesign the SHARP program are underway and members expect to present their recommendations to Army leadership soon for review and implementation.”

Update: After this story was published, an Army spokesman said the service will review the original decision to not prosecute Hughes after the February 2017 rape was reported. An Army official also clarified on background details about which echelon of command declined to prosecute the February 2017 rape, who signed off on Hughes’ GOMOR and when it was issued.

Kyle Rempfer was an editor and reporter who has covered combat operations, criminal cases, foreign military assistance and training accidents. Before entering journalism, Kyle served in U.S. Air Force Special Tactics and deployed in 2014 to Paktika Province, Afghanistan, and Baghdad, Iraq.