Over the past three years, soldiers from a specific Army National Guard task force have faced the most unconventional, but frighteningly likely, scenarios — both virtual and real.

And none of them involved bullets flying their way.

Soldiers with Task Force 46, formed in 2013, have faced simulated nuclear, chemical and biological attacks, nearly all focused on urban terrain, key points here in the United States that would see catastrophe at scale should the unthinkable happen.

RELATED

This week, about 170 soldiers from 10 states spent three days learning what it would take for them to help out should such a disaster strike New York City, perhaps the only “megacity” in the homeland.

They didn’t do it alone. In fact, they were in the Big Apple as one player in a larger team that involved local, state and federal agencies. Their part aligned mainly with the New York City Fire Department.

Senior leaders took in the flood of information on how they would operate in the city, what assets they’d need and how they could best contribute to the other entities.

Soldiers at the tactical level spent their time practicing chemical decontamination and learning from some of the world’s best subject matter experts on urban search and rescue.

They cranked away, safely, at rubble to rescue “victim” mannequins. They even went underground to crawl through black-out condition subway car simulators in search of injured or incapacitated people.

The task force has done events in Detroit, Michigan, and dispersed exercises with multi-state events across most of the nation. But last year, their in-person event had to go virtual due to the COVID-19 global pandemic.

“This year the big win was being able to get together face-to-face and do it hands on,” said Maj. Gen. Pablo Estrada, Task Force 46 commander, 46th Military Police Command, Michigan Army National Guard.

Recent years have seen the task force focus on biological, chemical or nuclear threats. That remains at the top of theirs list, but Col. Chris McKinney, task force chief of staff, said that they’ve also shared information with partners regarding potential delivery systems and ballistic threats, such as hypersonic weapons, should they be used against U.S. cities.

Task force leadership declined to provide details of some of the tactical and operational scenarios, citing security concerns.

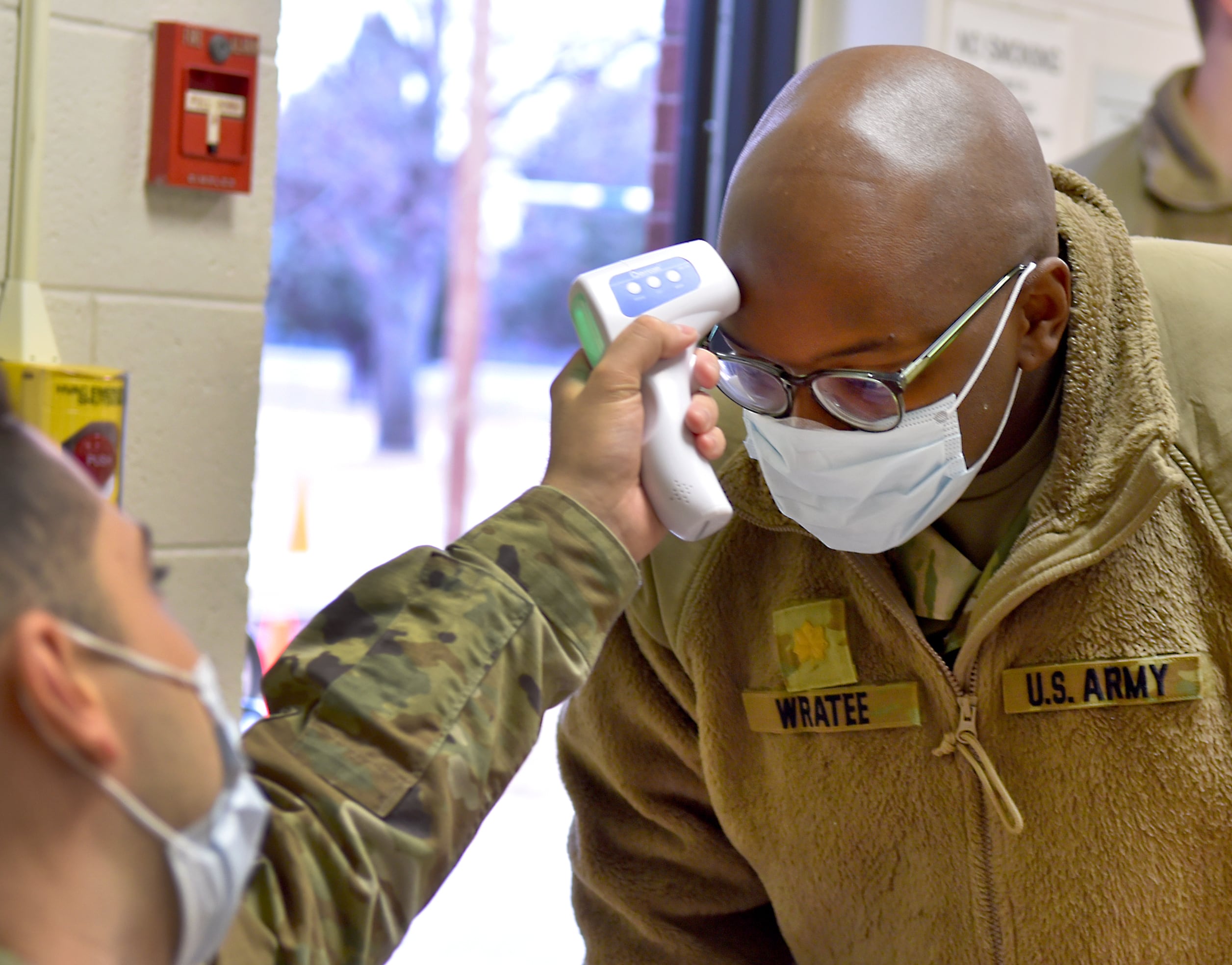

As this part of the task force refocuses on urban disaster/crisis response, other parts are wrapping up what became an 18-month commitment with real deployments stateside to help fight the COVID-19 pandemic, McKinney said.

That mission just ended on July 15.

Soldiers with the task force were spread out across 15 states, from California to Texas and up to Michigan. They coordinated responses and assisted medical personnel with everything from communications and logistics to patient care.

And it just so happens that some of the NYFD spend a few of their weekends in camouflage too.

Maj. Thor Johannessen is both a New York Army National Guard officer and a battalion fire chief in the city.

Even with his emergency response background, Johannessen said that this type of training gave him a different view of disaster response, an approach known as “consequence management” that differs somewhat from standard first-responder operations.

The newer approach is to better react to an event in a way that would prevent or reduce impacts of an attack or major disaster.

There were plenty of home team troops on this exercise as well.

Soldiers from the 204th Engineer Battalion and the 101st Expeditionary Signal Battalion of the New York Guard and the 119th Combat Sustainment Support Battalion of the New Jersey Guard participated.

One of those local New York Guardsmen included Lt. Col. Brian Higgins, who also works as a New York Police Department detective and interagency coordination chief.

Simply getting leaders, both military and non-military, out on the urban terrain, helps them get a truer picture of what they might face and all they have to consider should they be dispatched to the area, he said.

“We’re not in a sterile, straight military environment,” Higgins said.

Elements of the task force are headed to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for similar training in September and Los Angeles, California, in October, McKinney said.

Back in 2018, Army Times talked with Task Force 46 leadership. At the time, the Michigan Guard’s 46th Military Police Command had recently started their three-year effort to build capabilities for responding to a potential chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear attack in Detroit.

Key efforts included supplementing or filling gaps for local and state agencies, as well as doing mass decontamination that most agencies at the local level don’t have the capacity to undertake.

The soldiers also worked urban search and rescue at that time and have continued that training in the subsequent exercises over the past three years.

Another aim of the task force and others like it is to establish relationships with local and state agencies, even outside of their home station. Should Guardsmen be called up, it won’t be their first meeting with people in a crisis.

And after years of CBRN response, the mostly MP-heavy units that are part of the group have still more to do.

“Our only mission is not CBRN response, we also have a wartime mission, we have to start focusing on wartime detention operations in the combat situation, there’s a lot going on for the 46,” Estrada said.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.