The Army has confirmed that an officially approved app was built using code from a tech company with Russian roots that provides popular tools for app developers to send customized notifications to their users. The confirmation comes after a Reuters investigation spotlighted the situation.

At least 1,000 people downloaded the app, which delivered updates for troops at the National Training Center on Fort Irwin, California, a critical waypoint for deploying units to test their battlefield prowess before heading overseas. The app fell out of use in 2019 due to routine personnel changeover, and likely wouldn’t have been approved today due to more stringent IT protocols in recent years, according to an Army official and a service spokesperson.

Some of the app’s code came from a company known as Pushwoosh, which reportedly went to significant lengths to present itself as a U.S.-based entity, according to Reuters. Those efforts included fake LinkedIn profiles, phony addresses and more. The company’s founder, Max Konev, told the news organization that he was “proud to be Russian” in a September statement.

The U.S. considers Russia a top-tier threat to national security, alongside China. Officials in Washington have repeatedly warned of Moscow’s hacking chops and its ability to wage influence campaigns abroad, and cybersecurity experts told Reuters that Russia’s intelligence services may be able to compel companies like Pushwoosh to turn over their data, regardless of where it’s stored.

According to legal experts interviewed by Reuters, the company was able to circumvent industry regulations and government contracting rules against doing business with Russian companies. Such restrictions have tightened since Russia’s renewed invasion of Ukraine that began in February, and a growing number of companies have come under formal sanctions as well.

Pushwoosh is one of many software development companies that offer third-party coding solutions to other developers who are seeking off-the-shelf features to fold into their projects. According to the company website, Pushwoosh customizes its targeted notifications by collecting and storing a bevy of user data on its servers in Germany.

The Russian-owned entity gathers location data, device data and other potentially identifying information collected from apps that use its notifications code and pools it on its servers. A company blog post reveals it retains that data “eternally,” no matter how long it has been since a user has opened the app, unless a user turns off notifications or deletes the app.

The National Training Center application, published by the service’s TRADOC Mobile app portal and listed in both the Apple and Google app stores, “was developed in 2016″ using “a free version of Pushwoosh,” confirmed Army spokesperson Bryce Dubee in an emailed statement to Army Times and C4ISRNET.

It’s not clear what user data was collected from the NTC app and stored by Pushwoosh, and it’s not certain whether Russian intelligence services have obtained it or can access it. But even seemingly innocuous apps can feed targeting efforts: A 2020 VICE Motherboard investigation revealed U.S. Special Operations Command had been purchasing anonymized location data for several apps popular in the Muslim world, presumably to unmask and target individuals associated with terrorist groups.

Russia has historically denied accusations of cyber aggression and espionage. Pushwoosh founder Konev told Reuters his company “has no connection with the Russian government of any kind.”

Why did an Army app use Pushwoosh code?

An individual assigned to NTC, a major training center, created the application and submitted it for Army approval and publishing, according to Dubee. It was then approved.

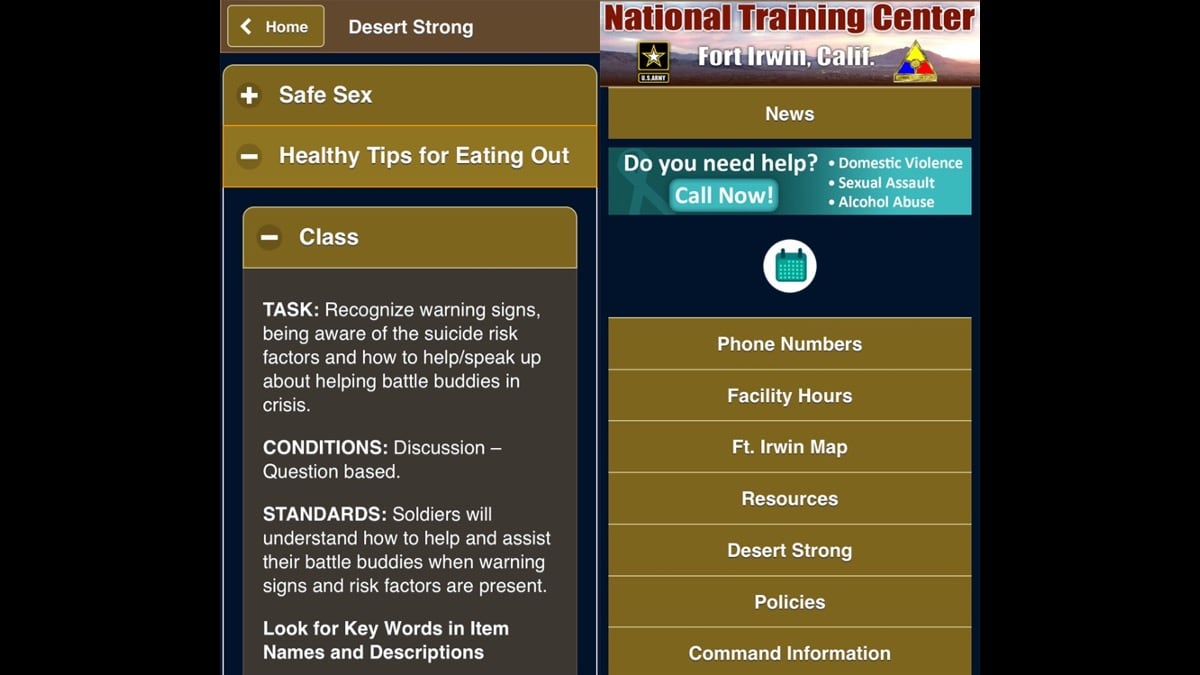

According to the app’s description in the Apple store, which was archived by App Aware’s API scraper, the NTC app advertised providing “the latest Fort Irwin news, information and social media updates” to users. It also included “quick-click buttons for calling post facilities, a community calendar and a map to popular establishments and much more.”

It’s not clear whether the map feature required users to opt into sharing their location with the app — and potentially with Pushwoosh. Regardless, the app saw fairly wide use; an archived listing for the app on Google Play store scraper APK Combo said more than 1,000 Android users downloaded it. Army Times and C4ISRNET could not confirm how many Apple devices had installed the app before it was removed from the App Store.

The NTC app fell out of use in 2019, an Army official said, after changes in personnel. But the potential risks went undetected for years after the NTC app was abandoned, the official added, until a “routine scan” of Army apps in March “determined the NTC app was not in compliance, not in use, and not able to be updated.”

Today, the app wouldn’t be approved at all “because regulations and guidance have become more stringent since 2016 [when it was developed],” and the Army “moved to have the app taken offline completely while conducting a routine review of authorized apps,” Dubee confirmed.

“Regulations do not authorize the use of free software when paid software is available, and consequently, the PM Army Mobile team would have immediately disallowed/disapproved the use of free software,” Dubee explained.

The spokesperson did not answer questions from Army Times and C4ISRNET seeking more information on what data the app collected and whether the service was aware of the company’s origins when it shut down the NTC app in March.

Davis Winkie covers the Army for Military Times. He studied history at Vanderbilt and UNC-Chapel Hill, and served five years in the Army Guard. His investigations earned the Society of Professional Journalists' 2023 Sunshine Award and consecutive Military Reporters and Editors honors, among others. Davis was also a 2022 Livingston Awards finalist.

Colin Demarest was a reporter at C4ISRNET, where he covered military networks, cyber and IT. Colin had previously covered the Department of Energy and its National Nuclear Security Administration — namely Cold War cleanup and nuclear weapons development — for a daily newspaper in South Carolina. Colin is also an award-winning photographer.