A kaleidoscopic hail of tracer fire swept across the alley — green, red, orange — casting a neon glow on the darkened streets of Mogadishu.

Shell casings showered down from helicopters as Spc. Arthur Houston’s heart pounded. He jumped out of the Humvee’s driver’s seat while a torrent of bullets whipped around.

The Somali fighters, some not yet teenagers, rattled AK-47 rounds from every angle, bursts of light then they vanished.

Every sense blurred. The acrid black smoke of tire fires filled his lungs as he crouched, boots scraping along the debris-littered ground. Houston squatted at the Humvee’s rear, popping up to return fire when the barrage broke. Pfc. Matthew Lagana ripped 7.62mm rounds from his M60 machine gun in the vehicle’s turret.

Spc. Gerard Gutierrez stepped away from the vehicle to return fire with his M16 and suddenly fell to the ground. He’d been shot in the neck.

“Gutierrez is down!” Lagana yelled.

The soldier lay motionless about 20 feet away in the kill zone. It could have been a mile.

About 10 seconds passed and instinct forced Houston’s legs to run, crunching broken glass and concrete.

“I don’t know I just did my training and I moved toward him, grabbed him, pulled him out of the line of fire,” Houston said.

Sweating and straining through layers of desert tan fatigues under a 22-pound flak jacket, Houston dragged Gutierrez back to the Humvee.

Once Houston had his friend under cover he knelt, putting a hand on Gutierrez’ bleeding neck.

Medics arrived and shoved Gutierrez under the vehicle for better protection from the storm of incoming fire. The neck wound threatened to suffocate him, so they cut a hole into his throat for air.

Vehicle commander Sgt. Frank Nanny broke the radio static, yelling for the field ambulance.

That night, Nanny took an enemy round to his Kevlar, the lead projectile lodged into the helmet. A ricochet grazed Lagana’s leg and RPG shrapnel pierced his flak jacket.

Nanny, Houston and the medics lifted Gutierrez into the ambulance. In all the patrols over the past three months during their 1993 deployment to Somalia, Houston never felt as vulnerable as when he was carrying Gutierrez to the vehicle.

The fight continued as the patrol pushed deeper into the war-torn streets of Mogadishu to rescue trapped Rangers and retrieve the bodies of downed Black Hawk helicopter crews, in what would later be memorialized in the film “Black Hawk Down.”

Weeks after the battle, Houston’s platoon leader, 2nd Lt. Bryan Puckett was told that he could nominate only one of his 40 soldiers for a valor award. Though reluctant to overlook the countless acts of valor he and others witnessed, the young lieutenant followed orders. He chose Houston.

Those minutes of bravery resulted in a recommendation for the Bronze Star Medal with a “V” for valor. The Army downgraded it to an Army Commendation Medal with “V.”

Houston’s actions were one of many by the men of 3rd Platoon, Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 87th Infantry Regiment, 10th Mountain Division leading up to and during the Battle of Mogadishu.

He was the only platoon member to receive a valor award for the deployment.

They ran security patrols, and hours-long firefights, retrieved bodies from an earlier Black Hawk crash and sustained their own wounded. All of this before 3rd Platoon helped rescue elite Delta Force operators and Rangers surrounded by thousands of fighters.

The platoon, hastily attached in the pre-deployment weeks to the larger support Task Force 2-14 received Army Achievement medals, a noncombat award, but saw no further recognition for the next 30 years.

After the deployment, the soldiers drifted apart, some stayed in the Army, most left. A few reconnected years later, sharing trauma and laughs. Some passed away. Neither the movie about the battle, nor the book upon which it was based, mentioned what they did. Years later news of upgraded awards for others who fought in that mission surfaced, some took it hard.

Over time, a few of the veterans gave their crew a nickname, “The Forgotten Bastards.”

Award upgrades

The Army announced in 2021 that it would upgrade 60 medals awarded to Rangers, Delta operators and other soldiers who fought in the Battle of Mogadishu, following a review ordered by the Secretary of the Army.

They served in Operation Gothic Serpent, which culminated in the Oct. 3, 1993 mission to snatch lieutenants of Somali warlord Mohamed Farrah Aidid. The military effort ran alongside a larger United Nations humanitarian mission.

In all, the upgrades included 58 Silver Star Medals, two Distinguished Flying Crosses and four Distinguished Service Crosses.

The upgrades followed the 2019 documentary, “Black Hawk Down: The Untold Story.” That film focused on the role of Task Force 2-14, consisting mainly of 2nd Battalion, 14th Infantry Regiment, 10th Mountain Division.

Retired Air Force Col. Randall Larsen made the 2019 documentary film to bring attention to the task force and its soldiers, which received little coverage in the earlier Black Hawk Down book and feature film book.

The new documentary stood as a historical corrective for 2-14.

But the “untold story” didn’t include 3rd Platoon, which had been attached to Task Force 2-14 shortly before the deployment.

As the 30th anniversary of the infamous battle approached, 3rd Platoon had yet to be recognized, or even included in the unit history of the mission.

A reunion

A year after the awards upgrades for the Mogadishu troops made news, 3rd Platoon saw, for the first time in 29 years, a few nods, ever so slight, to their service.

Even so, Ed Ricord, a retired Army Special Forces medic who served with 3rd Platoon during the Mogadishu mission, treating multiple casualties, decided the unit needed something of its own.

Ricord created his own tribute, a custom-rebuilt 1993 FLH Harley Davidson Eagle Eye Ultra Classic motorcycle. He took the bike to Texas for a surprise visit in March 2023 — to Rolando “Poncho” Carrizales, a soldier paralyzed after being shot during an earlier Black Hawk rescue mission.

Ricord first had “Poncho” sign the bike. Then he and his wife Laura traveled across the country over the next few months to collect more signatures from the unit before arriving at Fort Drum, New York for the anniversary.

It wasn’t until Oct. 3, 2023, three decades later, that roughly two dozen members of 3rd Platoon were recognized by their old unit for their service.

Lt. Col. Chris Turner, current battalion commander of 3rd Platoon’s old unit, pointed to their actions during the Battle of Mogadishu as examples for his soldiers to follow.

“What I’m trying to inculcate in my organization is a culture of grit and lethality, and what those men did in ‘93 was the epitome of grit,” Turner told Army Times.

The first Black Hawk Down

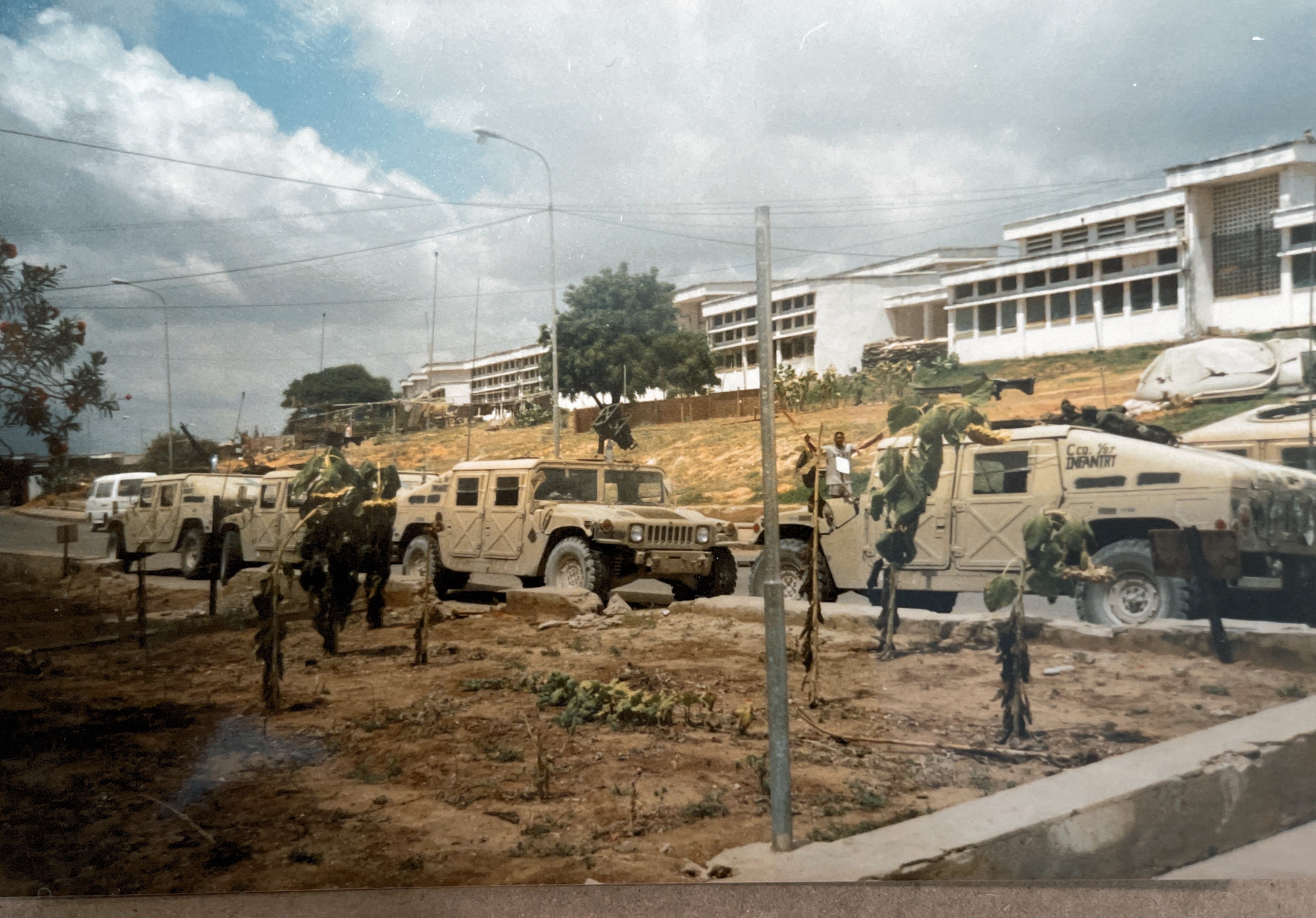

For nearly three months, the 40 soldiers of 3rd Platoon had lived a predictable routine at Mogadishu University, their home base in the country. They’d wake at 0530, load gear, ammo, water, rations and weapons into their Humvees. They’d grab chow at around 0900 and then they’d wait.

The platoon served as the quick reaction force, or QRF, for Task Force 2-14, supporting operations in Mogadishu. The infantry soldiers ran patrols on major routes, accompanied convoys and did whatever else the higher command told them. One odd-job involved guarding engineers from warthogs.

Members of the unit had gotten into an intense, four-hour battle with Somali fighters a couple of weeks before, on Sept. 13. Most thought that would be the combat highlight of the deployment.

At 0145, on Sept. 25, a soldier on watch at the university where 3rd Platoon lay sleeping spotted a fireball in the sky.

In minutes a first sergeant was shouting at the squad it was “go time.” A UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter was missing, and the QRF needed to go find them.

Staff Sgt. Olin Rossman roused 2nd squad, and in minutes everyone was suited up and ready.

Driver Pfc. Rolando “Poncho” Carrizales, vehicle commander Sgt. Willie Boult, M60 turret gunner Sgt. Brett Archibald, and Pfc. Gregg Long, a forward observer filling in as the door gunner, scanned the lanes as they tried to locate the downed helicopter.

Carrizales spotted a fiery glow and they rolled up to the smoldering wreck.

The smell of burning fuel and metal permeated the air.

For a few minutes they were alone as the convoy did an about-face, rolling back to their location.

A rocket-propelled grenade sailed through the air, reverberating waves of a deep, bass-like sound as it struck something behind them, creating an echoing slap as bursting shards of shrapnel sprayed on impact. All of them, save Archibald, leaped out of the vehicle to return fire.

Archibald ripped bursts of 7.62mm from his machine gun as the others fired their M16s.

Long leaned against the Humvee, firing from cover when Archibald spotted a boy, who looked about 12 years old, lugging a shoulder-fired rocket launcher out into the road. The boy could barely lift the thing but managed to fire it. The round fell short but sent a blast wave at them. Small arms fire peppered the men.

Carrizales fell to Long’s left, almost like he had just passed out.

Enemy rounds kept coming.

Rossman had pulled up moments before, directing vehicles to form a kind of arching perimeter around the crash site and lay suppressive fire from their .50 caliber, M60 machine guns and the recently fielded Mk19 40mm grenade launchers. He hopped out of his Humvee, approaching the crash site on foot. He saw the Black Hawk crew chief’s helmet smoking in the middle of the road. Three soldiers, the helicopter’s crew minus the pilot and co-pilot, were dead inside the charred hull.

He ran to Poncho, looking for a wound because he didn’t see any blood. Rossman spotted a one-inch hole on the left side of Poncho’s neck. Suddenly the blood shot out waist-high, spraying Rossman, who yelled for a medic.

Long didn’t think, he just got up and ran, yelling for a medic.

More small arms fire erupted, pinging all around Long, who danced in the middle of the semi-dark street trying not to get hit.

Sgt. 1st Class Eddie Ricord, a medic with the 5th Special Forces Group assigned to the task force, ran through a swarm of bullets unscathed to reach Poncho.

“It’s the bravest thing I’ve ever seen in my life,” Long said later.

Ricord sidled up to Poncho and Rossman, who had shoved field dressing after field dressing on Poncho’s wound, desperately trying to stem the bleeding, which had drenched Rossman’s desert brown uniform.

“What do we have here? You picked a fine place to try and lay down,” Ricord said.

“I think we need to get the fuck out of here,” Poncho replied, choking on his own blood before passing out.

“We’re working on it buddy,” Ricord said.

As Ricord treated Poncho and began loading him into another Humvee to evacuate, Rossman heard a series of shots and yelling.

Enemy rounds had pierced the Humvee’s windshield and struck Archibald in the leg.

Sgt. Willie Boult pulled Archibald from the turret and into the vehicle. Rossman jumped on the M60 to return fire, fumbling at first with blood-slicked hands.

Bullets screamed past, coming in red and orange tracer streaks and flashes from seemingly every window and doorway of the two- and three-story buildings that encircled their position.

As the firefight raged, soldiers wrenched the Black Hawk wreckage apart with tow cables linked to their Humvee to retrieve the bodies of the crew: Pfc. Matthew Anderson, Sgt. Ferdinan Richardson, and Sgt. Eugene Williams.

The pilot and co-pilot, Chief Warrant Officer 3 Dale Shrader and Chief Warrant Officer Perry Alliman had made it out before the convoy had arrived. The pair had left the downed chopper for cover. Alliman was burned and blinded, Shrader had a broken arm. Shrader used a pistol to kill one Somali fighter and warded off two others who rushed the wrecked aircraft, earning him the Silver Star Medal.

The sun rose, bringing with it better-aimed shots from the Somali fighters, who lacked the night vision devices that 3rd Platoon carried.

Long took over as driver and they headed back to their home base at Mogadishu University.

The group was within sight of the university, perhaps two blocks away, when another RPG struck Sgt. Christopher Reid, tearing off part of one leg and a hand.

That mission was the most combat any of the men had ever seen. It was only the beginning. The real fight had yet to come.

Rescuing the Rangers

On Oct. 3, about a week after the first Black Hawk crash, 3rd Platoon was playing volleyball at their headquarters when the call came.

Delta Force and Rangers were pinned down in the heart of Mogadishu. They’d captured their targets when Somali fighters shot down two MH-60 Black Hawks.

The platoon headed to a nearby port staging area where they waited as night fell. Poncho’s Humvee still smelled of blood and cordite from the previous week.

At around 2200 they rolled out in their hard shell Humvees, alongside United Nations Armored Personnel Carriers and tanks.

The heavier vehicles had not been involved in the light raid by the Rangers and didn’t support earlier ground movements to protect the attacking force, which used Humvees and helicopters to reach the market.

Pfc. Matthew Lagana, the M60 gunner on Houston’s vehicle, sat at the staging area, waiting to enter Mogadishu when a colonel walked by.

For the entire deployment, the Rules of Engagement were clear: fire only when fired upon. Each soldier was supposed to have a copy of the ROE in their breast pocket. That’s where Lagana carried his.

But this fight seemed different, every Humvee was stuffed with crates of ammunition, shoulder-fired rockets and any other weapon they could carry.

“Sir, what’s the ROE?” Lagana asked the colonel.

“Son, there are no rules of engagement tonight, shoot anything that moves,” the colonel replied.

“Our orders were to smash, shoot, destroy everything in the area not identified as American,” Rossman said later. “If the enemy could use it for cover or transportation, we were to destroy it.”

The crew had already modified some of their tactics after the first few firefights. They cut parachutes from flares. That was because most positions didn’t allow them to fire into the air, where they could blind the friendly “little birds” — small armed helicopter escorts above them.

Instead, they’d shoot the flares about 200 yards down an alley, which would help backlight fighters they could then identify and shoot.

Burning tires or debris piled on the roads, blocking nearly every intersection.

Houston drove his vehicle through eerily empty, quiet streets. The silence weighed heavily as he knew a fight was coming. In the distance, he could see U.S. helicopters firing into the city and enemy tracers slicing up through the sky.

The convoy turned a corner and Somali fighters unleashed a barrage of fire that continued through the night.

The thudding recoil of AK-47s sounded from every corner, punctuated by the choppy blast of PKM machine guns.

Then there was the whoosh and crash of RPG-7 grenades. On big targets, Somali fighters would unleash volleys of half a dozen at once. Devastating for a Humvee, the 85 mm RPG projectile had little effect on armor, even in a salvo of six or more.

But the steady bombardment forced the soldiers to hunker down in their vehicles or alongside them, as they awaited a break, however brief, to return fire.

The UN personnel carriers and tanks wouldn’t run through the obstacles, fearing mines or other booby traps. At times, 3rd Platoon soldiers would have to get out of their Humvees, exposing themselves to fire as they dismantled the obstacles to get through.

“We would fight to a stop, get out, return fire, load up, return fire, move 50 meters, stop, get out, return fire, load up, return fire, ad nauseam,” Rossman said.

To break through and get to the Rangers, Pfc. Keith Smith, a Mk19 gunner, fired volleys of 40mm that broke through the “baited ambush” that the Somali fighters had set alongside the route to the downed helicopters.

It took more than five hours of slinging rounds before they made it to the first helicopter crash site, said platoon leader 2nd Lt. Bryan Puckett.

Puckett said that Smith’s Humvee took the lead within the convoy and the vehicle crew was in constant contact as they pushed through to the crash site.

“He was the gunner in main contact with the final blocking position that allowed the convoy to reach the Rangers,” Puckett said. “His use of the Mk19 was the critical event that allowed us to break through enemy forces to reach the trapped Rangers.”

On this one mission, the platoon fired 22,000 rounds of 7.62mm from their M60 machine guns. Smith alone fired an estimated 1,600 rounds of 40mm grenades, Puckett said.

The platoon reached the first crash site, and split up, one group helping retrieve bodies from the downed helicopter while the other set up a defensive perimeter.

The tanks didn’t do much, until one pulled up near Rossman as he was unleashing round after round of 40mm into a building that kept spitting out sniper fire. Without warning, the tank fired a round.

“I thought my brain was coming out of my ears, the over-pressure was damn near too much to bear,” Rossman said.

In a kind of dreamlike moment, Rossman heard someone from his rear saying, “don’t shoot, don’t shoot.”

Puzzled, he looked ahead to see a Somali man carrying a body in a bloody blanket, walking down the middle of the street, oblivious to the battle raging all around him. The shooting stopped. The man kept walking. Once he passed, the fire resumed.

The convoy reached the crash site of Super 61. As part of the patrol recovered injured Rangers, others began cutting through the downed Black Hawk to recover the deceased.

Daybreak arrived and the men finally freed the body of Chief Warrant Officer 4 Cliff Wolcott, killed in the Black Hawk crash.

Once the wounded were loaded onto the vehicles, the convoy began to race toward the nearby soccer stadium, controlled by the Pakistani contingent of the UN force.

As the convoy rolled, Rossman heard that one of his soldiers, Gutierrez, had been hit. He stopped to check on his status. The convoy left without him.

Rossman never got word that the convoy was headed to the stadium. He had to drive back the way he came. On the way out there were 200 soldiers, 30 vehicles and a three-hour gun battle.

Now it was him with 20 soldiers and a fraction of the remaining convoy headed back to their original staging area.

Beyond some potshots, they made it back with little further contact and reached the port staging area.

A half hour later they were told there were still soldiers missing in the city and they’d have to go back in.

“Are you fucking kidding me?” was Long’s response.

But as they were reloading, the call came back to stand down. The mission was over. But the deployment was not.

Over the coming weeks, the platoon would mount up and patrol the area daily. They even returned to the Bakaara market, where Delta captured the warlord’s lieutenants, only days after the firefight, escorting what they suspected were either CIA or more Delta Force operators wearing civilian clothes. The mystery men were gathering more information about Aidid, the Somali warlord.

A cold homecoming

After wrapping up their deployment, 3rd Platoon was headed home for Christmas. From the oppressive heat of Somalia to the cold December of Fort Drum, New York, home of the 10th Mountain Division.

At first, their leadership sought to give the men who’d experienced some of the worst urban combat the Army had seen since Vietnam four weeks of block leave. That request was cut down to two weeks for holiday leave.

The men took what they could get and returned to duty after the holidays. They were then told they’d be headed down to Fort Pickett, Virginia for urban warfare training.

Despite likely being part of only a handful of soldiers in the Army who’d seen actual urban combat, they attended the training alongside the rest of Charlie Company, which had not deployed to Mogadishu, not as instructors or advisors — but as students.

Many took the move as standard Army bureaucracy. This was the training calendar and that ruled everything. But for others, it felt like another slap in the face.

What’s next for the ‘Forgotten Bastards’

The soldiers of 3rd Platoon fought through some of the bloodiest urban combat since Vietnam. Not only on the Oct. 3 rescue mission but in incidents that preceded it. Soldiers such as Carrizales, Archibald, Gutierrez and Reid would carry their physical wounds for life. Many in the platoon would bury the mental burden, only to have it resurface in surprising fits over the decades.

Outside of a small, heartfelt ceremony held on a sunny Fort Drum afternoon 30 years later, these soldiers have yet to see the Army recognize what they endured and sacrificed.

Lt. Col. John Suprynowicz, who is a Mogadishu veteran as well and witnessed firsthand the actions of 3rd Platoon, has pushed for the Army to review the combat actions of this element.

He confirmed the numerous acts of bravery on multiple missions during the deployment, especially on the Oct. 3-4 rescue. And he, like many in this platoon, thinks that reviewing those acts is the fair thing to do.

Editor’s Note: Research for this article included multiple interviews with members of 3rd Platoon, reporting on past events involving Mogadishu veterans, material from the book and “Black Hawk Down: A story of modern war,” the book’s film adaptation, and the book “Behind the Gun: Poncho’s Last Walk.”

Correction: This article has been updated to provide the correct name spelling and rank for Spc. Gerard Gutierrez.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.