More than a century ago, 13 Black soldiers stood at the gallows near Fort Sam Houston, Texas, convicted by an all-white jury two weeks earlier with no chance to appeal.

The men, along with 97 Buffalo Soldiers of the 3rd Battalion in the all-Black 24th Infantry Regiment, had gathered arms and rushed to aid two fellow soldiers who were arrested after one tried to intervene as a white policeman dragged a Black woman into the street. The deadly violence that erupted became known as the 1917 Houston Riots.

The 13 soldiers’ deaths, carried out as punishment for the melee, marked the largest mass execution in Army history. Another six men were executed later.

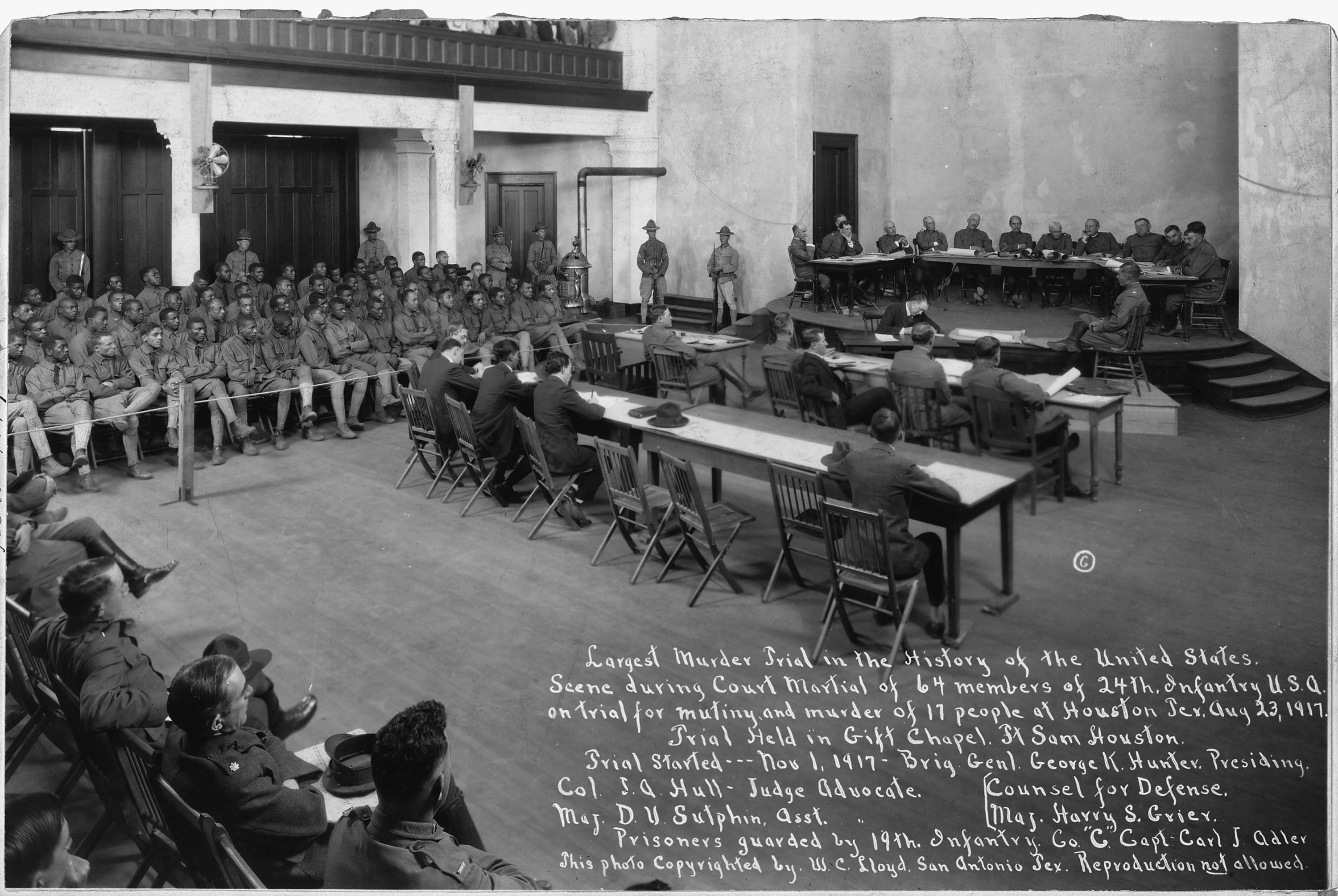

In total, the Army court-martialed and convicted a total of 110 soldiers from the regiment — including the 19 who were executed — on charges of mutiny, assault and murder.

Army Secretary Christine Wormuth on Monday approved a recommendation by the Army Board for Correction of Military Records to formally overturn those convictions.

“After a thorough review, the Board has found that these soldiers were wrongly treated because of their race and were not given fair trials,” Wormuth in a release. “By setting aside their convictions and granting honorable discharges, the Army is acknowledging past mistakes and setting the record straight.”

The incident led to military justice reforms that established due process for troops as well as a legal review board.

“Even with the backdrop of entrenched, state-sanctioned racial segregation, there was an immediate public outcry about the miscarriage of justice,” Army Brig. Gen. Ronald Sullivan, chief justice of the Army’s Court of Criminal Appeals, told a crowd gathered at the Buffalo Soldiers National Museum in Houston on Monday, the Washington Post reported.

The 110 Buffalo Soldiers of the 3rd BN, 24th Infantry Regiment, who were charged in the incident had deployed from New Mexico to Texas in 1917 for guard duty during construction at Camp Logan, a post built as the United States entered World War I.

Racial segregation in Houston, restrictions on Black soldiers and residents, and slurs hurled by white workmen at the construction site contributed to an already tense environment, according to the Texas Historical Commission.

On Aug. 23, 1917, two Houston police officers burst into a private citizen’s home to search for suspects, according to the commission’s website. When a Black woman objected, one of the policemen dragged her into the street in her undergarments.

Pvt. Alonzo Edwards tried to intervene and was pistol-whipped and arrested. Following his arrest, Cpl. Charles Baltimore, a Black military policeman, went to the local police to learn more about Edwards’ condition. He was also beaten and arrested.

Though Camp Logan officials had ordered soldiers to stay on post, more than 100 grabbed weapons and entered the city. In the aftermath of the riots, 17 lay dead, including five police officers, according to the commission.

The Army removed the 24th Regiment from the city and held a series of three military trials in San Antonio, the first of which involved nearly 200 witnesses over 22 days. The defendants were sentenced to various punishments, including hard labor and prison sentences as long as a lifetime behind bars.

Thirteen were sentenced to death. The men requested a firing squad, considered a more honorable form of execution for military men. Those requests were denied. Instead, they were sentenced to death by hanging.

In October 2020 and December 2021, descendants of three of the executed — Jesse Ball Moore, Thomas Coleman Hawkins and William Nesbit — requested to review the courts-martial and petitioned for posthumous pardons with the help of the South Texas College of Law.

“With the support of our experts, our dedicated Board members looked at each record carefully and came up with our best advice to Army leaders to correct a miscarriage of justice,” said Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Army for Review Boards Michael Mahoney, who oversaw the review. “We’re proud of the hard work we did to make things right in this case.”

After reviewing the cases, the Army Board for Correction of Military Records acknowledged that the proceedings were “fundamentally unfair,” according to an Army release.

“As a Texas native, I was grateful to participate in this process early in my tenure at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery in San Antonio, and I am proud that the Army has now formally restored honor to Soldiers of the 3-24 and their families,” Army Undersecretary Gabe Camarillo said in the release. “We cannot change the past; however, this decision provides the Army and the American people an opportunity to learn from this difficult moment in our history.”

The Army announced that relatives of soldiers involved in the incident may be entitled to benefits.

Family members may apply online at https://arba.army.pentagon.mil/online-application.html or submit a DD Form 149, Application for Correction of Military Record by mail to: Army Review Boards Agency (ARBA), 251 18th Street South, Suite 385, Arlington, VA 22202-3531. Applications should include documentation to prove a relationship to one of the 110 formerly convicted soldiers.

Family members or other interested parties may request a copy of the corrected records from the National Archives and Records Administration, in accordance with NARA Archival Records Request procedures found at: https://www.archives.gov/veterans/military-service-records.

For more information about these corrections, please contact the Army Review Board Agency at: army.arbainquiry@army.mil

*CORRECTION: This article has been corrected to accurately list the number of days the first of three courts martial proceedings took place.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.