Two Army and one defense department research agency have launched a project to develop stronger drugs to counter a World War II-era biological weapon that experts worry could reemerge to threaten troops today.

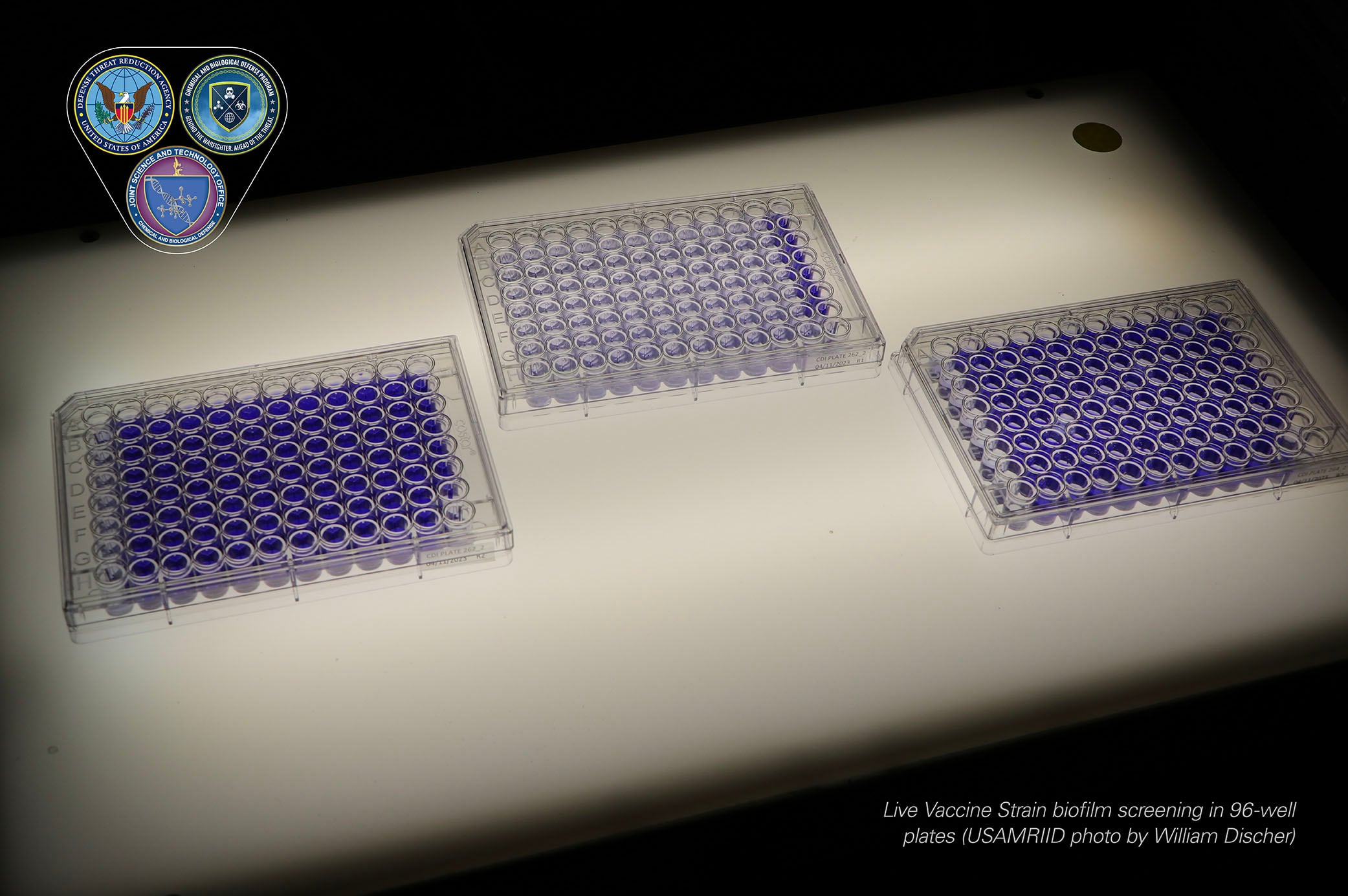

Researchers with the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, or DTRA, Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases and Walter Reed Army Institute of Research announced on Jan. 6 an effort to develop a treatment for tularemia bacteria, in the event that adversaries attempt to use it as a biological weapon.

The bacteria are designated as a Tier 1 select agent, which means it presents “the greatest risk of deliberate misuse with most significant potential for mass casualties,” according to a DTRA release.

Biological weapons have received more attention in recent years for a variety of reasons.

Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical and Biological Defense Deborah Rosenblum noted in 2022 that the threat of chemical, biological and nuclear attacks to military forces both at home and abroad had triggered new thinking, funding and a renewed focus for the first time since the beginning of the Iraq War in 2003.

RELATED

The assistant secretary noted trends, such as advances in laboratory technology and easier-to-access information online about how to create and deploy such weapons, made countering those threats “vastly more difficult” in a “rapidly changing” environment, Army Times previously reported.

Tularemia is bacterium that is primarily transmitted to humans from rodents and rabbits, and causes skin ulcers, fever, cough, vomiting and diarrhea, according to the release.

The Soviet Union’s Red Army used weaponized tularemia against German troops during the World War II Battle of Stalingrad, later revealed by former Soviet scientist Dr. Kenneth Alibek, who was previously involved in the Soviet Union’s bioweapons program, according to the release.

In his 1999 book, “Biohazard,” Alibek detailed the use of tularemia during the battle and later efforts by Soviet scientists that included loading smallpox on intercontinental missiles, according to a 2001 article in the journal “Military Medicine.”

Alibek’s analysis included reports that tularemia was deployed by the Soviet military during the battle and hundreds of thousands of tularemia infections were reported by troops on both sides.

But Military Medicine article authors argued that high numbers of infections were also likely linked to a natural outbreak of the disease during the prolonged siege, due in part to disrupted hygiene and sanitation systems and soldiers eating food contaminated by exposure to rodents.

Antibiotic treatments for tularemia exist, but rising resistance levels are driving research for stronger methods.

The new effort won’t only combat the tularemia-causing bacteria, but antibiotics being developed could also treat biothreats such as Bacillus anthracis (anthrax), Yersinia pestis (plague), Burkholderia mallei (glanders), and Burkholderia pseudomallei (melioidosis), according to the release.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.