Two Civil War soldiers who infiltrated Confederate territory to steal a train and destroy the enemy railroad system were posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor by President Joe Biden on Wednesday.

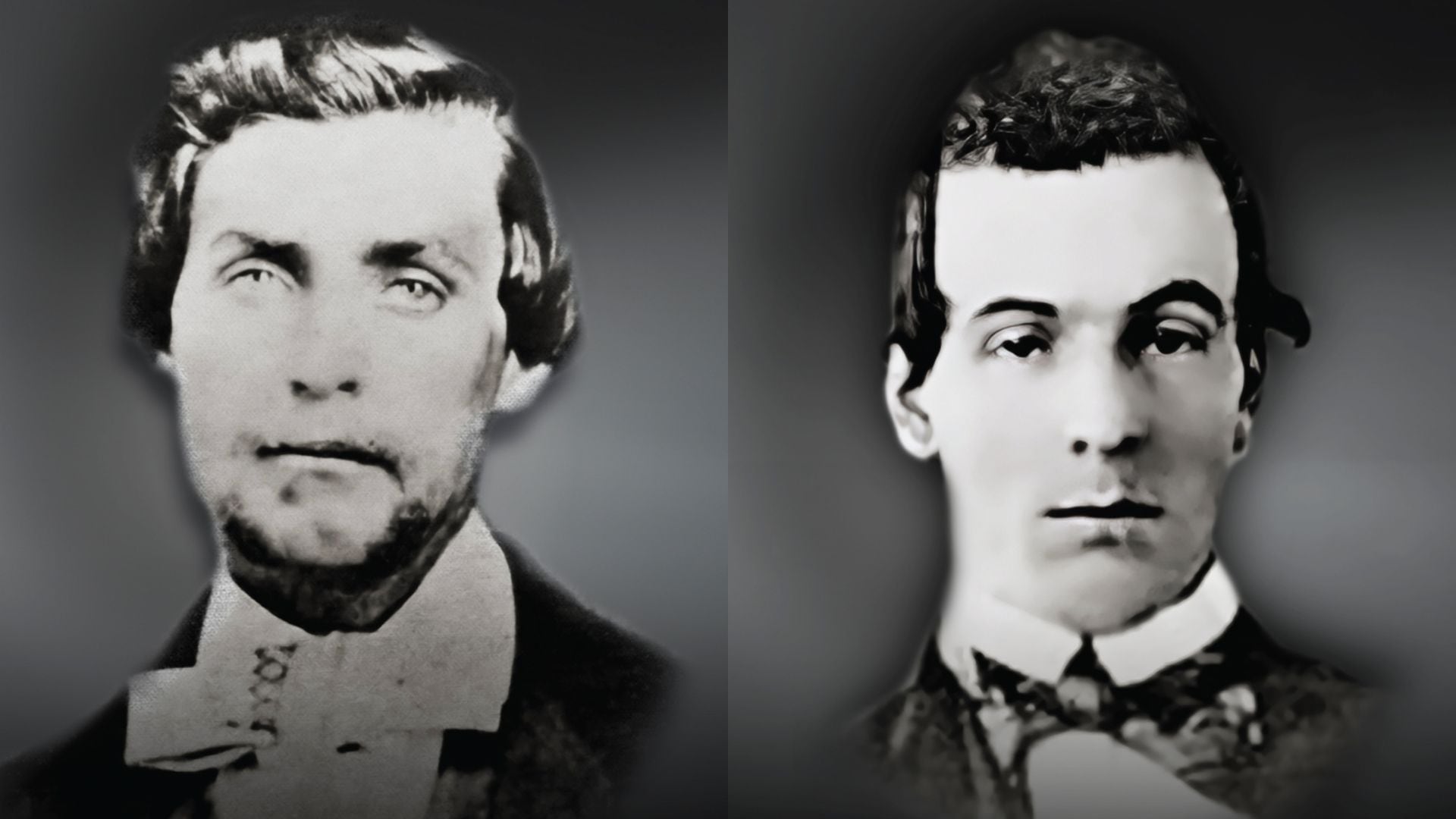

Pvt. Philip Shadrach and Pvt. George Wilson, members of the 2nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment, are finally set to receive recognition as participants in what is known as the “Great Locomotive Chase.”

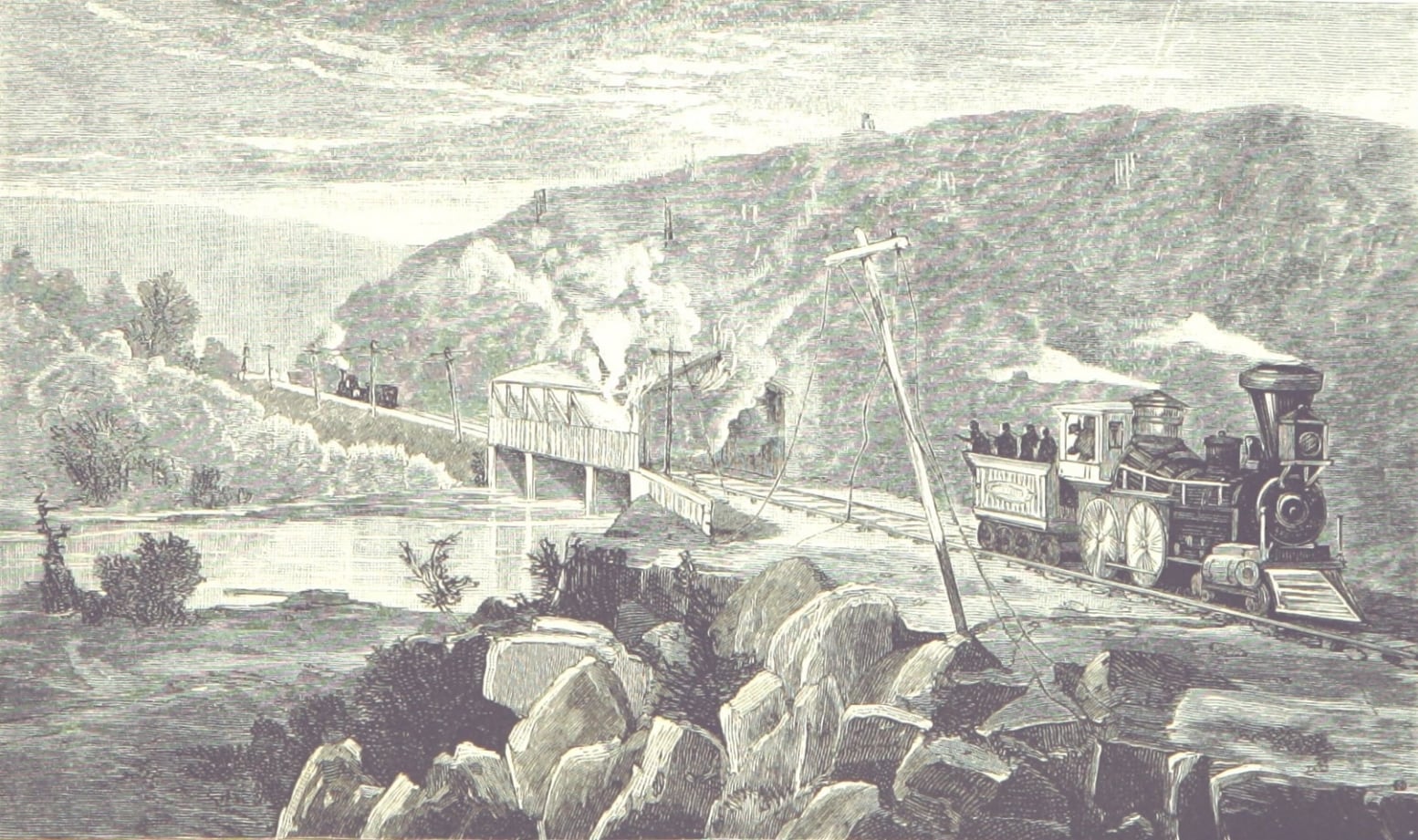

On April 12, 1862, the pair joined 20 other Union soldiers and two civilians in commandeering a train in Georgia, before driving it north while demolishing Confederate railroad tracks and telegraph lines. Both men were captured and executed by hanging.

Now, 162 years later, the soldiers are being recognized for their previously overlooked contributions to an event that others were awarded Medals of Honor for — including Pvt. Jacob Parrott, the very first service member to be presented with the military’s highest award for valor.

“It touches me deeply,” Theresa Chandler, the great-great-granddaughter of Wilson, said Tuesday at a media event. “I just get so emotional with it, thinking he had such bravery and valor.”

The plan was straightforward. By sabotaging the Western and Atlantic Railroad, the men would cut off the Confederacy’s ability to move supplies or reinforcements from Atlanta, Georgia, to Chattanooga, Tennessee, and deprive them of making strategic advances. Shadrach, Wilson and the others met in Big Shanty, now Kennesaw, Georgia, where they took over a locomotive known as the “General” and implemented their operation. But the Confederates caught up, and captured the raiders.

“More than anything else, it is the story of American soldiers far from home committing extraordinary acts of service and bravery on behalf of their country,” said Dr. Shane Makowicki, a historian from the Army Center of Military History.

He and another historian explained that whether it was an initial oversight in the documentation process or a lack of individuals advocating on their behalf, the bravery of Shadrach and Wilson was exactly the same as the other men who participated, most of whom received the Medal of Honor for their actions.

“It was just, at that moment during our history, nobody was there to stand up for them and move this through,” said Brad Quinlin, a historian and author, who also suggested that one of the reasons for the delay may have been that their infantry regiment was decimated in another battle, leaving few who could push for them to receive the distinction.

Approval to bestow the decorations on the soldiers came in the fiscal year 2008 annual defense policy bill, though it still took time to get the paperwork in the right hands and across the finish line.

But, not everyone involved in the risky undertaking has received recognition for their actions.

James Andrews — the leader of the group, which became known as Andrews’ Raiders — and William Campbell were not eligible for the Medal of Honor as civilians, though Quinlin said he’s working on requests to get them awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Additionally, one remaining soldier involved in the group, Samuel Llewellyn, does not hold the country’s highest military decoration. According to Quinlin, he turned it down, thinking he did not deserve it as he was caught before reaching the rendezvous point.

Shadrach and Wilson are buried at Chattanooga National Cemetery in Tennessee, Quinlin shared with Military Times.

Kimberly Chandler, a great-great-great-granddaughter of Wilson, described the story of her ancestor as “one of intense dedication and commitment, intense bravery and camaraderie amongst a group of men that had only known each other for a short time, believed in the mission and believed in the sacrifice of what they were doing to preserve the Union.”

Jonathan is a staff writer and editor of the Early Bird Brief newsletter for Military Times. Follow him on Twitter @lehrfeld_media