The top Marine is building the Corps of 2030 ― but today’s combat operations are siphoning forces for the future fight.

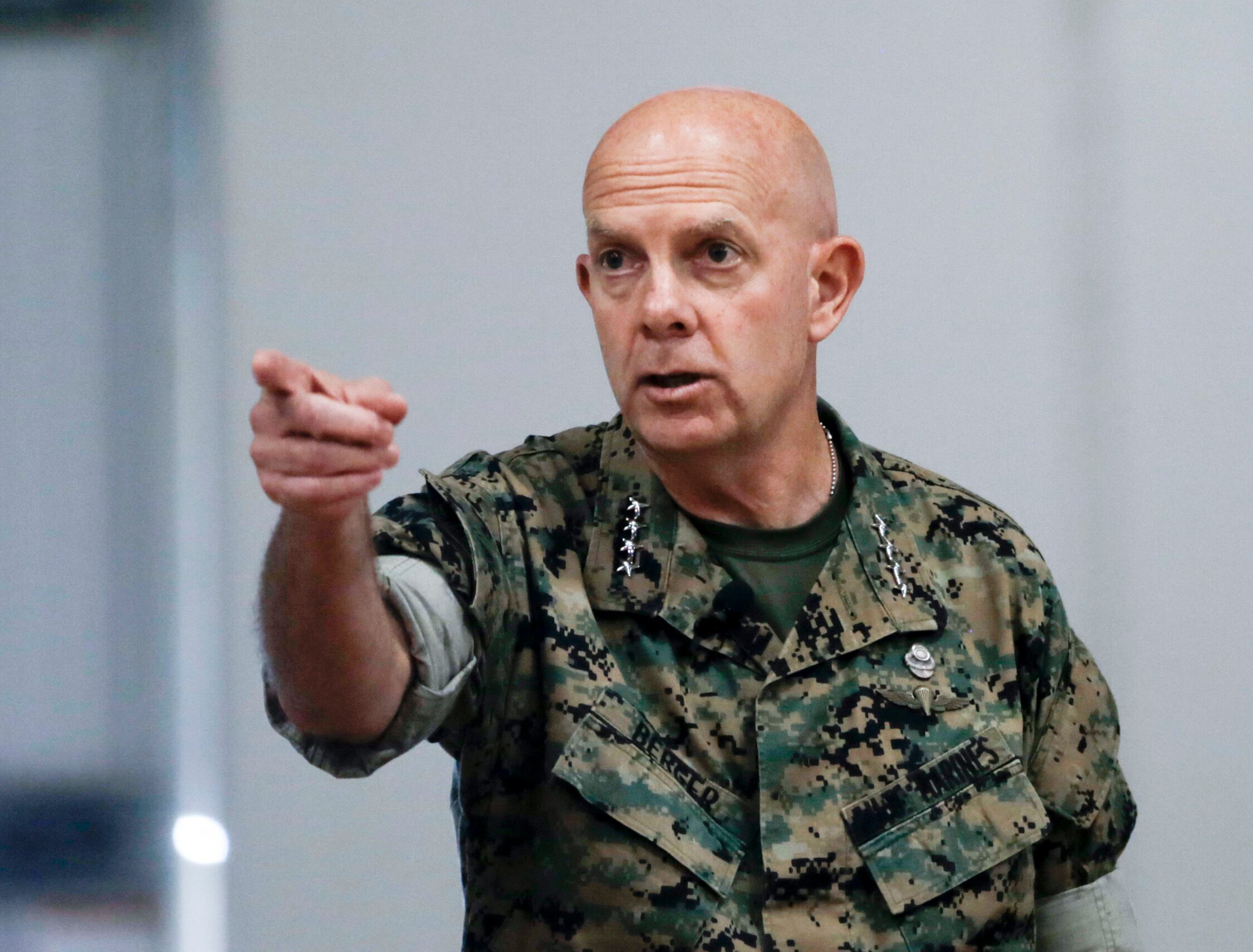

Speaking at a Center for a New American Security event Tuesday, Marine Corps Commandant Gen. David Berger touched on changes in the size of the Marine Corps, how it trains and the way it fights in the coming years.

Since taking over the post in 2019, Berger issued his Commandant’s Planning Guidance and has hinted at getting rid of some legacy systems and adding new platforms and formations.

While the 2021 budget does show initial investments in new weapons, such as ship-sinking missiles and a likely reduction of more than 2,000 Marines, more is in store, he said. At a recent hearing he said that it’s likely there will be further manpower cuts next year and beyond.

“We have to get smaller to get better,” Berger said at CNAS.

RELATED

The commandant said that the Corps’ current size is larger than it has been in recent decades and it needs to get back to its “fighting weight.”

There are more than 186,000 Marines in the ranks today as compared to slightly more than 176,000 Marines before 9/11.

None of these decade-out goals are happening in a vacuum. Marines are on the ground around the world, floating in Marine Expeditionary Units on the high seas and dying in combat operations such as the one that took the lives of two Marine Raiders in Iraq on Sunday.

While all concepts and analyses point to competition and potential conflict in the Pacific, the Middle East still continues to draw forces, Berger said.

That doesn’t stop the U.S. from reaching its goals on dealing with threats from China or Russia, but it can slow down the transition, he said.

Berger said many of the changes he’s proposing and planning take a look at are where the service needs to be in a decade and working back from that point. That’s mostly an attempt to avoid a “whipsaw” approach to drastic changes in manpower or programs that’s caused problems in the past.

And those changes likely would have come from his predecessors had they not been immersed in the high deployment cycle of combat in both Iraq and Afghanistan, he said.

He also credited his time serving in the Pacific before becoming commandant, which included multiple, high-level, war gaming scenarios that signaled future problems.

“If we don’t change it’s going to be ugly somewhere in 6-7-8-9 years,” Berger said.

While some schools of thought have looked ever more sophisticated long range weapons and standoff to prevent the Chinese military or other adversaries from striking U.S. interests, Berger said that ignores everything in between, especially allies who expect a U.S. presence.

And Berger has categorized Marines, in their expeditionary role, as the “stand-in forces” that will exploit areas inside the bubble of an adversary’s weapons engagement zone.

But for those tactical forces, the next fight won’t look like the counterinsurgency fight that their leaders experienced, he said.

One example, Berger noted, was the over reliance on comprehensive knowledge of the battle space.

“We fell in love with situational awareness, like we couldn’t do anything without it,” Berger said.

But in the future, when jamming and network attacks might mean degraded communications, the commandant said he thinks “junior leaders are going to operate faster and senior leaders are going to be nervous.”

And that can be seen in something as seemingly simple as striking a target.

Current methods in counterinsurgency or counter terrorism operations mean a long list of approvals that go all the way up and back down a chain of command.

That’s necessary in the limited strikes with civilians in danger but it’s far too slow and too cautious for a large scale combat scenario.

“That’s not realistic in a dynamic fight at all,” Berger said. “We have to change our behavior and accept that there’s going to be collateral damage, there’s going to be civilian casualties.”

Even training will have to change in light of a sensor-filled globe and an always watching adversary.

“It wasn’t long ago we could take the whole joint force out to Alaska or China Lake and nobody could see what you were doing,” Berger said.

That’s no longer the case. So, a lot more training will have to be done ‘out of sight.’

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.