Seventeen-year-old Dalton Beals knew just what to do when his mom, Stacie, heard a chirping cricket in their garage.

Rather than stomp on the little creature, he scooped it up and transported the critter to safety.

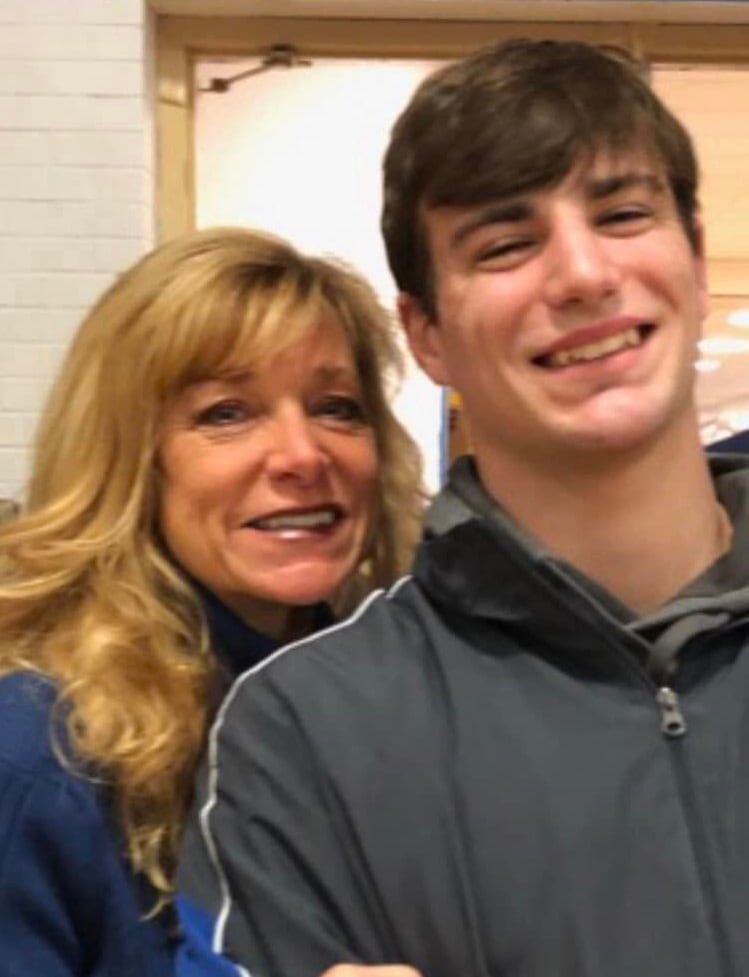

“That was him — he just had a kind, gentle nature about him,” Stacie Beals told Marine Corps Times in a March interview.

When he was 18, the good-natured teenager decided to pursue a path with the Marine Corps, looking to challenge himself and serve his country.

His mom made him promise he’d sign up for a combat support job, rather than something riskier.

But on June 4, 2021, during the grueling final stage of boot camp at Parris Island, South Carolina, Pfc. Dalton Beals died at age 19.

A command investigation later pointed the blame at his senior drill instructor, Staff Sgt. Steven T. Smiley, for allegedly failing to monitor his recruits despite dangerous heat levels.

That’s not how Smiley’s defense team sees it.

“It’s pretty clear that this young man, Recruit Beals, had some existing heart condition, and it was pretty severe,” retired Lt. Col. Colby Vokey, Smiley’s civilian lawyer, told Marine Corps Times in June. “This tragedy happened while he was going through recruit training, but it could have happened at any time.”

RELATED

Smiley is slated to go on trial in mid-July for negligent homicide and other charges. If the trial proceeds as planned, a jury of his peers — likely troops from the South Carolina Marine base and the Eastern Recruiting Region, according to Vokey — will weigh the facts that come to light and determine whether Smiley was responsible for the recruit’s death.

But whether Beals died from his senior drill instructor’s alleged malfeasance, as prosecutors contend, or from an unpreventable heart issue, as the defense team argues, a sad truth remains.

A young man who — like every recruit or service member who dies — was more than just a statistic, more than just his role in the military, is gone.

And those who loved him are still coping with what that means.

‘Gentle giant’

Growing up in New Jersey with two older sisters, the easygoing Dalton Beals was described as a “gentle giant” by his family and friends.

Well-liked by his teachers, Beals worked hard in school, even taking classes at a local community college while in high school.

The sometimes-quiet teen found a passion in sports, from wrestling to football.

He played tight end and defensive line for the school’s football team under coach Mike Healy, who described Beals to Marine Corps Times as “one of the hardest workers.”

“He never ever gave up or quit on a drill, on a play or anything,” Healy said, adding that since Beals’ death the young man’s jersey number, 81, is given out in honor of him to a dependable player who puts the team first on and off the field.

A bit of a prankster, Beals every so often surprised his mother by jumping out of nowhere, then belly-laughing heartily. But Stacie Beals was most surprised when she learned her son was interested in joining the military.

Inspired in part by connections who served in the Marine Corps, and drawn to the challenge the service presented, Dalton Beals signed up for boot camp in February 2021.

He shipped off to South Carolina, where he was assigned to Parris Island’s Company E, Platoon 2040, and began training on March 30, 2021, according to a Marine Corps investigation later conducted by the command.

The island is located on the Atlantic coast and surrounded by swampy creeks.

In April 1956, a drill instructor led his recruits on a disciplinary hike into one of them, Ribbon Creek, by night.

Six recruits drowned, and the drill instructor was convicted of negligent homicide after a sensational trial.

The Ribbon Creek incident is still taught to drill instructors as a cautionary tale, The Washington Post reported in 2016.

In Beals’ first few weeks of boot camp, the weather was still temperate. In letters home, the recruit’s few complaints centered on the humidity and sand fleas.

Stacie Beals found herself racing to the mailbox to read letters from her son each week, which often were brief but described his experience at boot camp.

She worried if he was making friends, but he detailed for her and his sisters the quality of food, grumbled about his clunky military-issued eyeglasses and reported he did not find many of the physical requirements to be as tough as he imagined.

Behind the drill instructor

Steve Smiley, 35, grew up in Clarkston, Michigan, a Detroit suburb, according to his mother, Melody Smiley.

Like Beals, and perhaps like many of the young men who are drawn to the physical challenges of the Marine Corps, he played football and wrestled in high school.

Smiley enlisted in the Corps because he wanted to be a part of something bigger than himself and provide for his family, his mother said. He was determined to join the best of the branches, and that seemed to him to be the Marine Corps, even though most of the veterans in his family had served in the Army, according to Melody Smiley.

He ended up as a firefighter, with the goal of serving in a civilian fire department upon his retirement, Melody Smiley said.

As a lance corporal, he was selected to be on the all-Marine wrestling team, according to a 2011 Marine Corps news release. At the time, his coach, then-Maj. Dan Hicks, described Smiley as mentally tough and a hard worker.

“He is one person I know I can give a beating to and he will keep coming back for more,” Hicks said in the 2011 release.

Steve Smiley’s loved ones portrayed him as an outgoing guy, dedicated to his friends and family, including his wife and two children.

“I know that I can always count on him to be there in both the good times and the more difficult ones,” Jay Brimacombe, who has been friends with Steve Smiley since fifth grade, said in an emailed statement.

When Brimacombe was stuck in a boat that had stopped working in the middle of a lake, Steve Smiley went out in a little boat to drag him back to shore, Melody Smiley said. When a relative’s car broke down, he drove for two hours to pick him up, she said. When his younger cousins are struggling financially, he finds a way to get some extra cash into their hands.

“He’s not this big, scary drill instructor,” Melody Smiley said. “He’s a family man.”

The staff sergeant’s military decorations include the Navy and Marine Corps Achievement Medal, Marine Corps Good Conduct Medal, Sea Service Deployment Ribbon, Global War on Terrorism Medal, National Defense Service Medal and Navy Meritorious Unit Commendation, according to Marine spokesman Maj. Philip Kulczewski.

“His love for the Marine Corps hasn’t waned one bit, as remarkable as that may sound,” said Vokey, Smiley’s civilian lawyer.

Into the Crucible

As spring wore on in South Carolina in 2021, temperatures regularly rose into the 80s and sometimes above 90 degrees Fahrenheit.

In the middle of Dalton Beals’ training cycle, Steve Smiley became his senior drill instructor after a personnel shakeup in the company, in which at least one instructor was suspended, according to the command investigation. The command investigation doesn’t specify the cause of that suspension but does indicate that it stemmed from “an investigation related to events occurring during the prior training cycle.”

Before then, Smiley had served as a drill instructor for three training cycles, according to the command investigation, which was completed September 2021. Stacie Beals said she received it around December 2021, and Marine Corps Times obtained it in July 2022.

Superiors who evaluated Smiley after previous training cycles gave him mixed reviews, with some describing him as a “phenomenal asset” but others saying he had trouble teaching information rather than just enforcing discipline, according to the command investigation.

Apparently because of the last-minute nature of his assignment, he never went through senior drill instructor training, which is designed to “ensure the Marine understands the proper role of the senior drill instructor and has the appropriate experience, maturity, and temperament necessary to perform the duties as a senior drill instructor,” the investigation noted.

A Marine senior drill instructor is supposed to serve as a parental figure, who takes a firm approach to recruits while still being someone they can confide in, one Marine Corps news release states.

But in surveys during Beals’ boot camp cycle shortly after Smiley became the senior drill instructor, some recruits said they felt uncomfortable alerting him if they had medical or other problems.

“He doesn’t listen,” one recruit wrote. “He just screams go away.”

The survey results prompted base officials to counsel Smiley sometime that spring on how to conduct himself. Some recruits reported that he improved somewhat after that.

In June 2021, after nine weeks of training, Beals and the rest of Echo Company embarked on the culmination of Marine boot camp: the Crucible.

First introduced in 1996 at the behest of then-Commandant Gen. Charles Krulak, according to an official history of the South Carolina base, the Crucible is a 54-hour capstone training event involving multiple physically demanding activities and approximately 40 miles of hiking.

Teams of recruits work together to complete the exhausting Crucible, with limited food and sleep.

The toughness is the point, as the Corps readily admits. Through the pressure of the Crucible, the theory goes, Marines are formed.

And if temperatures creep into the 90s at the South Carolina depot, as they did the day Beals died, drill instructors are required by Marine orders governing the Crucible to monitor their recruits closely.

The redacted copy of the investigation written by the command, which conducted dozens of interviews, found that an instructor — whose name was withheld but who likely was Smiley based on the charges he faces — failed to follow those instructions.

During the Crucible, even as temperatures soared to what the Marine Corps terms black-flag conditions, the drill instructor made his recruits perform “unauthorized,” additional physical activity, the command investigation found.

On June 4, Day Two of the Crucible, the recruits still had to complete an event involving four miles of marching on foot, in Kevlar helmets and gloves, according to the command investigation. Two recruits fell out of the hike, prompting a pause in the hike as corpsmen, enlisted medical personnel, tended to them.

As the hike continued, Beals became hunched over and wobbly, other Marine recruits told investigators. At one point, the recruits saw him wander off in search of water.

Because two other recruits were getting medical treatment for overheating, there was some confusion about whether Beals was one of them, according to the investigation.

When one recruit asked a drill instructor, whose name was redacted in the command investigation, whether Beals was getting treated, the drill instructor brushed the recruit off, allegedly saying, “Get out of my face,” the investigation states.

For more than an hour, Beals went unaccounted for, according to the investigation. When it became clear that he was missing, the unnamed drill instructor at first asked whether Beals was part of the group and “seemed mad at first,” but “then appeared worried,” a recruit told investigators.

But it was too late. By the time Beals was found in the woods, he had no pulse.

Following his death, Marine officials determined that Beals had earned the title of Marine.

When Stacie Beals got a call after midnight on June 5, 2021, there was little the Marine Corps told her about her son’s death.

“Never in a million years would I have thought I’d be getting that knock like I did,” she said, adding she could not imagine what had happened.

The first time she saw a photo of her son in his uniform was in media reports about his death, she noted.

The Beals family still decided to go to the graduation ceremony a few weeks later and meet with their son’s fellow platoon members.

It was not until months later, Stacie Beals said, that she received the investigative report from the Marine Corps detailing what allegedly unfolded.

The report stated that an initial autopsy had determined Dalton Beals had died from overheating, which the command investigation called “likely preventable.”

Some media outlets drew comparisons to the death of Pvt. Raheel Siddiqui, a Muslim Marine recruit who died in an apparent suicide in 2016 after being hazed by his drill instructor.

The command investigation into Dalton Beals’ death called for legal or administrative action against the unnamed senior drill instructor, and administrative action against two commanders. Two commanders were subject to individual boards of inquiry, Kulczewski, the base spokesman, confirmed.

The investigation concluded that while Smiley technically was qualified for the senior drill instructor role, “he did not have the maturity, temperament, and leadership skills” necessary for the role, based on his superiors’ evaluations from previous training cycles and interviews with recruits in Beals’ company.

In November 2022, Smiley was charged with negligent homicide; obstruction of justice; cruelty, oppression or maltreatment of subordinates; and failure to obey orders, a charge with four specifications, or descriptions of the alleged offense, according to his charge sheets.

Negligent homicide is defined as the killing of another person by “an absence of due care” for others’ safety, according to the manual for courts-martial.

The charge sheets, obtained by Marine Corps Times via public records request, contain extensive redactions that obscure specifics of the allegations against Smiley.

Vokey denied to Marine Corps Times that Smiley had violated orders or mistreated recruits. The lawyer, who is a Marine veteran, argued the main witnesses to the alleged mistreatment described in the command investigation were recruits at the time and lacked a frame of reference for how things should be conducted in the Marine Corps.

“I think we will know at trial a lot better when we get those recruits on the stand and are able to question (them) thoroughly about their opinions,” Vokey said.

In a query to Kulczewski, Marine Corps Times sought comment from the prosecution but did not receive a response from the spokesman to that aspect of the query.

Not all of the recommendations in the command investigation involved punishment for those who allegedly failed to take action that could have prevented Beals’ death. Some of them urged the Marine Corps to tweak the way it conducts recruit training.

The investigation report suggested changes to how the Crucible, technically an essential activity permitted even in black-flag conditions, is conducted in high temperatures. Corpsmen should be required to check every recruit for signs of heat injury, the report stated.

Recruits shouldn’t face a stigma when they ask for medical treatment, investigators stressed. The day he died, Beals refused to sit down and insisted he was just tired, even though other recruits noticed he was struggling, according to the command investigation.

And all senior drill instructors, absent extraordinary circumstances, should have to go through the training course to prepare them for the role, rather than being thrown into it like Smiley, according to the report.

Training and Education Command didn’t respond by publication to a request for comment about whether it has implemented these recommendations.

A delayed trial

Smiley’s three-week trial before a general court-martial, which tries service members for the most serious crimes, tentatively was scheduled to begin April 24, Kulczewski said.

Then new evidence came to light, prompting military judge Marine Col. Adam Workman to delay the trial, first by nearly two months and later an additional month, to give lawyers more time to review the evidence and hash out the legal issues it raises.

One reason for the delay was that the prosecution became aware of a Naval Safety Center investigation on Feb. 1. Litigation over whether the investigation could be used as evidence has since been resolved, with the judge determining that it couldn’t be used, according to Vokey.

Another reason for the delay: the revelation that a medical examiner had conducted a second autopsy of Beals.

The first one, conducted by the Beaufort County Coroner’s Office in South Carolina, determined Beals died from hyperthermia, or overheating.

But in the professional opinion of Dr. Gerald Feigin, who conducted that autopsy at the request of Stacie Beals, Dalton Beals died from a severe, unpreventable cardiac issue, not hyperthermia.

Feigin told Marine Corps Times in April that the pathologist who conducted the previous autopsy had examined only about half of Beals’ heart. An employee with that coroner’s office told Marine Corps Times the office can’t comment on or publicly release autopsy reports.

“I find it reprehensible that anyone is charged with a crime in this case,” Feigin emailed the defense team in March, according to a copy of that email in court documents.

RELATED

Stacie Beals, a floor registered nurse on a cardiac unit, told Marine Corps Times in April that she didn’t view the findings of the second autopsy as particularly relevant.

“Heat stroke can cause cardiac arrhythmia,” she said, adding, “I have no doubt that if it wasn’t for Steven Smiley, my son would be here today.”

If the trial goes as scheduled, it will be up to a jury composed of Marines of rank equal or senior to Smiley’s to decide his fate.

Every day, Melody Smiley prays for the jury to clear her son, and she prays that the Beals family will find peace after their devastating loss.

She told Marine Corps Times that she feels her son has been made a scapegoat.

“It’s just this horrible burden that we feel for our son and on ourselves, too, because he is our only boy, and we love him so much,” she said. “My heart just breaks for him.”

As the families, and the lawyers, were preparing themselves for a trial, the case was brought back into the public consciousness in April as another recruit, Pfc. Noah Evans, 21, died at the South Carolina base during a physical fitness test.

An investigation into the death of Evans — a native of Decatur, Georgia — recently closed. Marine Corps Times has requested that investigation from the Corps. And in June, Pvt. Marshall Hartman, 18, died in what Marine officials called “a non-training incident.”

Two years after Dalton’s death, the Beals family continues to find ways to honor his legacy. “Some days it still doesn’t seem real,” Stacie Beals said.

Dalton Beals and his cousin Derrek Beals, 21, were born only three weeks apart and raised like brothers. The pair grew up in the same town, going to the same school and playing sports together.

At memorial events for Dalton Beals in the months after his passing, more people showed up than could cram into one room, said Derrek Beals, who still visits the graveyard with his family to be close to his “built-in best friend.”

“You don’t realize how many lives someone touches until after, unfortunately,” he said.

One Marine who became close with Dalton Beals as they trained in the same company is expecting a baby son in October, that Marine told Stacie Beals.

The boy will be named Dalton. ■

Irene Loewenson is a staff reporter for Marine Corps Times. She joined Military Times as an editorial fellow in August 2022. She is a graduate of Williams College, where she was the editor-in-chief of the student newspaper.

Jonathan is a staff writer and editor of the Early Bird Brief newsletter for Military Times. Follow him on Twitter @lehrfeld_media