In mid-October, a new policy document on the Marine Corps’ website caused a stir among Marines preparing to transition to civilian life.

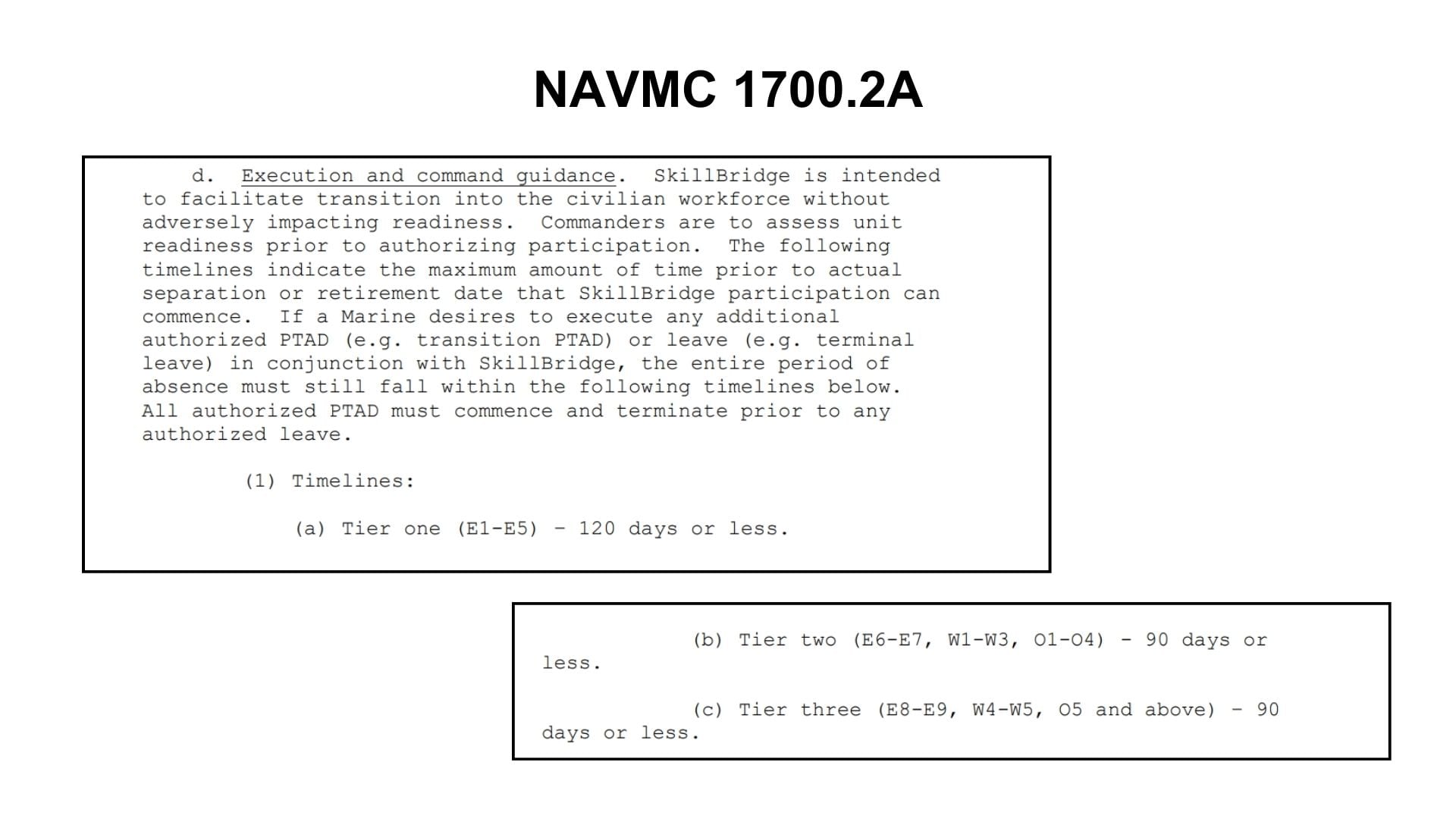

The document, providing direction to the active duty force, announced Marines would be limited to three or four months in SkillBridge ― the Defense Department program that allows service members to spend up to six months in civilian internships before leaving active duty. The document was posted on the Corps’ online “library” of publicly releasable publications, orders and directives.

But it turns out the document the Marine Corps released was “premature,” and the service hasn’t yet made any changes to its policy on SkillBridge, according to Marine spokeswoman Maj. Danielle Phillips.

SkillBridge allows soon-to-be veterans to work or train full-time at civilian workplaces, in a wide variety of fields, during their final months in the military. Meanwhile, they still get compensation and benefits from the military.

On Nov. 1, more than two weeks after the policy document was posted, Marines who handle the SkillBridge programs at each installation received an email letting them know that policy had been rescinded. A Marine official in the Corps’ Personal and Professional Development office sent that email, a confirmed source who asked to remain anonymous told Marine Corps Times.

“The policy update was pulled back for corrections,” reads the email obtained by Marine Corps Times. Each Marine installation has a point of contact for SkillBridge in the education or transition center, according to a Marine Corps fact sheet on the program.

The limits on time in SkillBridge “will be in effect upon completion of the revised guidance, keeping with the Commandant’s intent to focus on mission readiness,” according to the email.

“To clarify, the policy established by NAVMC 1700.2, dated December 2022, is still in effect,” Phillips said via email to Marine Corps Times on Nov. 8, referring to the policy that allows Marines a maximum of six months in the program. “Should any policy changes be approved, they will be announced via” Marine administrative message.

Phillips didn’t respond to a follow-up query from Marine Corps Times asking how the document, entitled NAVMC 1700.2A and dated Oct. 14, had been published prematurely. She didn’t respond by time of publication to a query about when any policy changes would go into effect or who was tasked with deciding on them.

The Corps hasn’t published a Marine administrative message alerting Marines to the error and clarifying the SkillBridge policy. Phillips didn’t respond by time of publication to a Marine Corps Times query about whether the service has informed Marines of the change via other channels.

In October, meanwhile, news of apparent limits on SkillBridge caused whiplash for some Marines who were on their way out of the Corps.

The now-rescinded policy would have limited the maximum time before separation or retirement that Marines can begin a SkillBridge program to four months for those of the rank sergeant and below and three months for staff noncommissioned officers, commissioned officers and warrant officers. That would have been a significant drop from the Marine Corps’ current maximum of six months.

The email that Marine points of contact for SkillBridge received on Nov. 1 says Marine commanders may either approve SkillBridge applications under the existing policy from December 2022 or require Marines to submit applications under the rescinded policy’s “tier” system, which puts limits on time in SkillBridge based on rank.

The Corps’ rules would have set the strictest time limits in the military.

The Army and Air Force allow the Defense Department’s maximum of six months, according to each branch’s respective website. The Navy in March made the maximum three or four months for more senior sailors but has kept the maximum to six months for junior enlisted sailors.

How SkillBridge works

SkillBridge began as a pilot program in 2011 to make it easier for service members to find work as the country emerged from the Great Recession. The DoD formally established the program in January 2014.

In fiscal year 2022, 22,548 separating service members participated in the program, a Labor Department leader told Congress in May. That year, there were a total of 174,813 service members who separated from the military, according to Pentagon data.

SkillBridge opportunities are available in fields as far-ranging as electrical construction, management consulting and book publishing, according to the list of authorized partners.

The program is designed to be a win-win for service members and employers, according to the SkillBridge website. Civilian partners get access to highly trained and motivated workers at no cost, while service members get training and work experience, which sometimes translates into offers of full-time employment.

But during their time in SkillBridge, service members aren’t working at their military jobs.

The Corps’ now-rescinded limits on the program would have meant Marines weren’t eligible for the longer opportunities, and some Marines transitioning out of the Corps would have had to scramble to make new plans.

On Reddit, LinkedIn and Instagram, active-duty Marines and Marine veterans expressed confusion, consternation and nonchalance about the apparent policy change. At least one installation, Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, North Carolina, published a guide to SkillBridge eligibility that relied on the now-rescinded policy.

Marine Maj. Antonio Contreras was thrilled when, early in October, he received an opportunity to spend six months working at the State Department. Contreras, a judge advocate and foreign area officer, must retire from the Marine Corps in July 2024 after 20 years, he told Marine Corps Times Oct. 23.

When the Marine Corps seemingly announced it was halving the time Contreras and Marines of similar rank could spend in the SkillBridge program, Contreras was left in limbo, hoping the State Department would still accommodate him.

He said he first found out about the apparent limits on SkillBridge from a coworker who had heard from an installation’s SkillBridge coordinator ― who later confirmed it to him directly. Meanwhile, Contreras saw news of the document spreading across social media.

“It was disheartening,” Contreras said Oct. 23. “There are opportunities to help you transition out of the Marine Corps, and all of the sudden all of that is swept from under your feet.”

Contreras ultimately worked out a three-month internship with the State Department, though he said Oct. 26 not every organization might have made a similar accommodation for Marines. For now, his request to the Marine Corps stands at three months.

The premature policy document also dictates that senior Marine leaders — of the paygrades E8-E9, W4-W5, O5 and above — must get the endorsement of a general officer in their chain of command before embarking on SkillBridge. Under that policy, those high-ranking Marines wouldn’t have been allowed to do SkillBridge if it would create a staffing gap.

That would have been a step up from the DoD’s requirement that service members get approval for SkillBridge from a field-grade commander with nonjudicial punishment authority.

The now-unpublished policy document encourages commands to establish a formal process for determining the effect of Marines’ participation in SkillBridge before disapproving requests. Commands should have the same criteria for evaluating requests from officers and enlisted Marines, the policy says.

The unpublished document also notes that participation in SkillBridge can affect special or incentive pay, typically offered to keep Marines in hard-to-fill or less desirable roles.

Reevaluating SkillBridge policy

The “premature” policy document was labeled as being from Commandant Gen. Eric Smith, directed to all Marines on active duty. At the bottom of the first page are the words “Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited.”

The Marine Corps webpage where the document had been linked as late as Nov. 8 now reads, “CONTENT NOT FOUND.” The webpage where the current SkillBridge policy, from December 2022, had been linked reads the same.

Phillips, the Marine spokeswoman, acknowledged that the Marine Corps is evaluating its SkillBridge policy.

“It is imperative that the service evaluate and assess the efficacy and impact of these programs and initiatives over time,” she said in the email to Marine Corps Times. “SkillBridge is one of the many programs currently being assessed by the service to ensure we balance the needs of the individual Marine with Congressional intent and a mission-capable Marine Corps.”

The Marine Corps’ now-unpublished policy document came seven months after the Navy tightened its own rules regarding SkillBridge.

In March, the Navy restricted the maximum time in the program to four months or less for senior enlisted sailors and lower-ranking officers, and three months or less for officers of the rank of commander ― the same paygrade as a Marine lieutenant colonel ― and up. Previously, the Navy had stated sailors “normally” shouldn’t spend more than four months in the program, but the maximum still had been six months.

But the Navy’s policy from March is looser than the one in the “premature” Marine Corps policy: Sailors up to the rank of petty officer second class (the same paygrade as a Marine sergeant) can still do SkillBridge for up to six months, the DoD’s maximum.

Irene Loewenson is a staff reporter for Marine Corps Times. She joined Military Times as an editorial fellow in August 2022. She is a graduate of Williams College, where she was the editor-in-chief of the student newspaper.