BLETCHLEY PARK, England — British codebreakers cracked Nazi Germany's encrypted secrets but did such a good job of keeping silent that their work was nearly lost to history.

Now a letter from Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower is helping to underscore the importance of Bletchley Park, the once-classified home of the World War II codebreakers. The letter, unveiled for the general public Tuesday at the historic site, offers a heartfelt tribute to the men and women who labored in blacked-out rooms for years to crack the Enigma code and beat the Nazis.

"The intelligence which has emanated from you before and during this campaign has been of priceless value to me," Eisenhower wrote to Stewart Menzies, the wartime chief of the Secret Intelligence Service, in 1945.

"It has simplified my task as a commander enormously." Eisenhower wrote just weeks after Nazi Germany surrendered. "It has saved thousands of British and American lives, and, in no small way, contributed to the speed with which the enemy was routed and eventually forced to surrender."

The letter from the wartime Allied military commander in Europe once hung on the office wall of John Scarlett, the head of the British intelligence agency MI6, from 2004 until 2009. It became public in 2010 when a history of the secret services was compiled.

The letter's release comes as the Bletchley Park Museum, 50 miles (80 kilometers) outside of London, enjoys renewed interest after being featured in "The Imitation Game." The 2014 film, starring Benedict Cumberbatch, tells the story of Alan Turing, a computer science pioneer and architect of the effort to crack Nazi Germany's Enigma cipher.

During the war, codebreakers at the one-time country estate were sworn to secrecy — a pledge taken so seriously that some still refuse to discuss their work. Bletchley's importance remained secret until the 1970s, when wartime intelligence officer F.W. Winterbotham published "The Ultra Secret" about the effort to crack the codes. Turing's contributions became widely known after documents about the program were declassified.

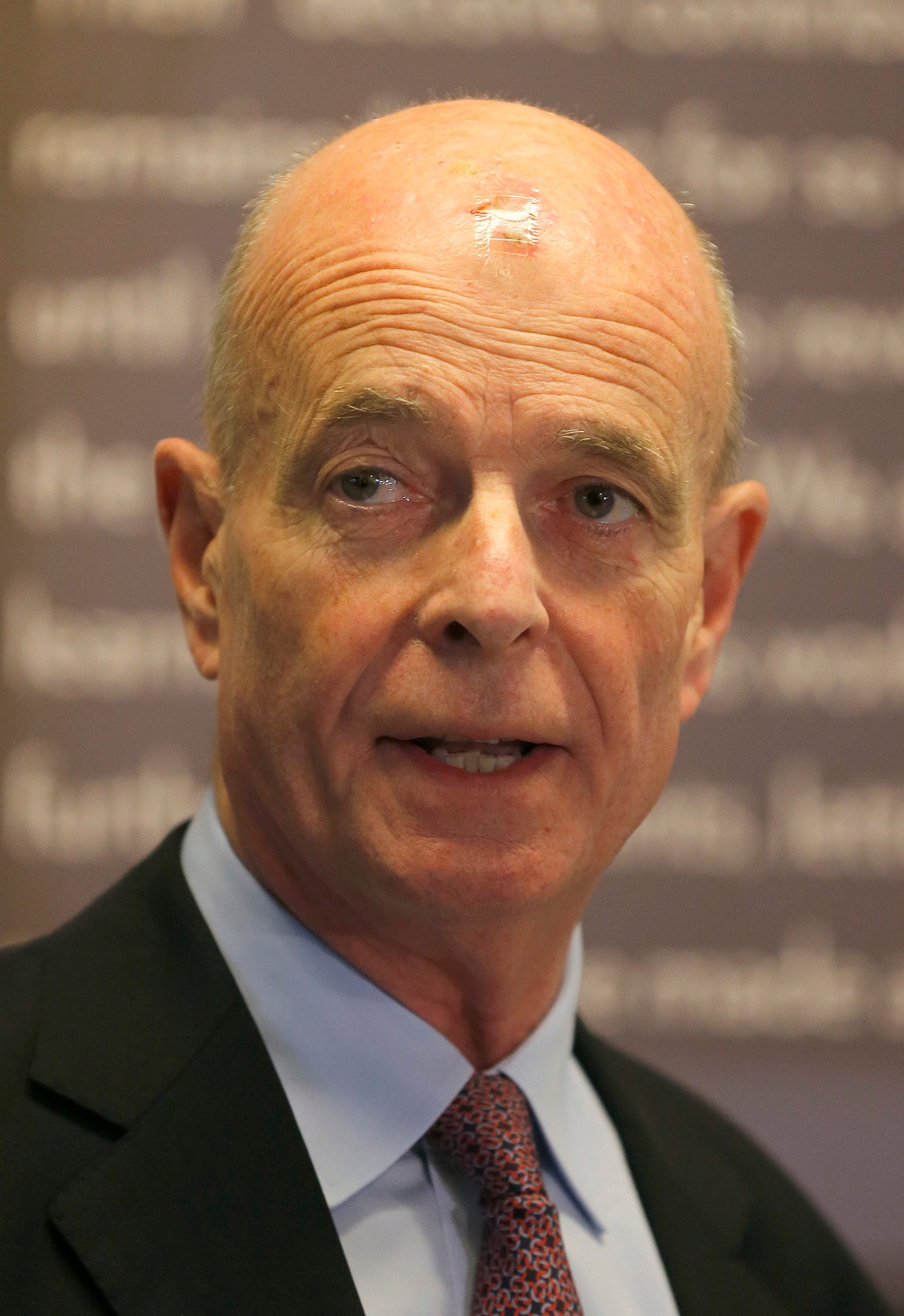

Former MI6 chief John Scarlett talks to the media as the letter from U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower is put on display on March 15, 2016, at Bletchley Park in Bletchley, England

Photo Credit: Frank Augstein/AP

As recently as 1994, historians had to fight to prevent the estate from being bulldozed to make way for a supermarket. It was saved and restored with an 8 million pound ($12.2 million) renovation program. Among the first visitors in 2014 was the former Kate Middleton, the Duchess of Cambridge, whose grandmother — and grandmother's twin sister — worked at Bletchley during the war.

Eisenhower's letter also highlights the so-called 'special relationship' between Britain and the United States, which includes intelligence sharing to this day.

But sharing the deepest of secrets did not come without controversy. In the interwar years, British authorities saw America as a "leaky sieve" and were reluctant to share information because they had grave reservations about how it would be used, said Niall Barr, a military historian and the author of "Eisenhower's Armies: The American-British Alliance During World War II."

"It really was unprecedented at the time," Barr said of intelligence sharing. "Things we take for granted now did emerge at the period of crisis."

By 1941, however, Americans were working alongside British codebreakers at Bletchley Park.

But the former reluctance was reflected in Menzies' reply to Eisenhower's letter, which is now at the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas.

The letter praises Eisenhower for recognizing the work of the Bletchley Park codebreakers, and expresses his "unbounded admiration" for the help Ike offered in ensuring the "proper usage of the material" — apparently for not tipping off the Nazis that the code had been broken.

"Without that help and the unstinted sacrifice of a large body of American specialists at Bletchley Park, I am confident the service would have been inadequate for your needs," Menzies wrote.

Barr said the exchange offers a glimpse of a particular time — a moment when Europe was in ruins, when an exhausted Germany had surrendered and in which a popular commander famous for his warm grin acknowledged the still top-secret efforts of his allies in the only way possible.

Barr had a twinge of sadness as he thought about it.

"In some respects, many of the people for whom this letter would have meant the most are not with us anymore." Barr said. "Many of them would have been pleased to know that he recognized their efforts."